Ten years ago, Croatia became the 28th member of the European Union and since then it has achieved its most important strategic goals and reduced the development gap with the ‘historic’ members to some extent, but due to the opening of European doors to its workers, it is facing a huge emigration of population. EU membership is one of the most significant events in Croatia’s history, together with NATO membership, which was achieved four years earlier and had been its main foreign policy goal since its independence.

Croatia submitted its application for membership on 21 February 2003. The Commission positively assessed the application in April 2004. Already two months later, on 18 June 2004, Croatia was granted the official status of candidate for membership and was supposed to start negotiations in March 2005, but under the condition of full cooperation with the Hague Tribunal, which insisted on the arrest of fugitive general Ante Gotovina.

The negotiations were therefore postponed for several months. They finally started on 3 October 2005, after the Hague Chief Prosecutor, Carla del Ponte, confirmed Croatia’s full cooperation with the International Criminal Tribunal. The Croatian negotiations were long, five years and nine months, longer than any other current member.[1] The final chapters were closed on 30 June 2011 and, after signing the accession agreement and ratification in the member states, Croatia joined the EU on 1 July 2013.

The negotiations were also burdened by cooperation with the Hague Tribunal and the Slovenian veto due to a bilateral dispute over the Gulf of Piran.[2] In the last year of this decade, Croatia achieved all its European integration goals: on 1 January 2023 it became a member of the Eurozone and the Schengen Area.

The Croatian Minister of European Affairs, Goran Grlic-Radman, celebrates the accession to the Schengen area on 1 January 2023

Benefits of the European Union membership

Three and a half years after the earthquake that devastated Croatia, the reconstruction of buildings and infrastructure continues, mainly thanks to EU aid. Two earthquakes in March 2020 damaged some 26,000 buildings in Zagreb, Petrinja and Sisak County. To repair the damage caused by the earthquake, Croatia received EUR 2.5 billion from the EU Solidarity Fund and the Recovery and Resilience Facility, designed as part of the Next Generation EU.[3]

Under this programme, conceived with the aim of mitigating the consequences of the Covid 19 pandemic, Croatia will receive an additional EUR 10 billion by 2026 (corresponding to 17% of Croatian GDP), of which EUR 6.3 billion in grants and EUR 3.7 billion in low-interest loans.

Taking population and GDP as a reference, Croatia is the largest recipient of European funds, which is not at all surprising considering that it is the youngest EU member state. Since 2013, when it joined the Union, Croatia has paid EUR 5.3 billion to the EU budget against EUR 17.1 billion received, thus registering a surplus of almost EUR 12 billion.

For Croatian citizens, European funding is undoubtedly the most tangible benefit of EU membership. The importance of European funds became particularly evident after the earthquake in 2020, but it is also reflected in many other projects, from the Pelješac Bridge to regasification plants and a whole series of reconstructions of railways, hospitals and schools.

“We see that Croatia has progressed how investors perceive it, because its rating has increased. If we also compare interest rates, they are now among the lowest in the European Union,” said Christoph Schoefboeck, President of the Management Board of Erste Bank.[4]

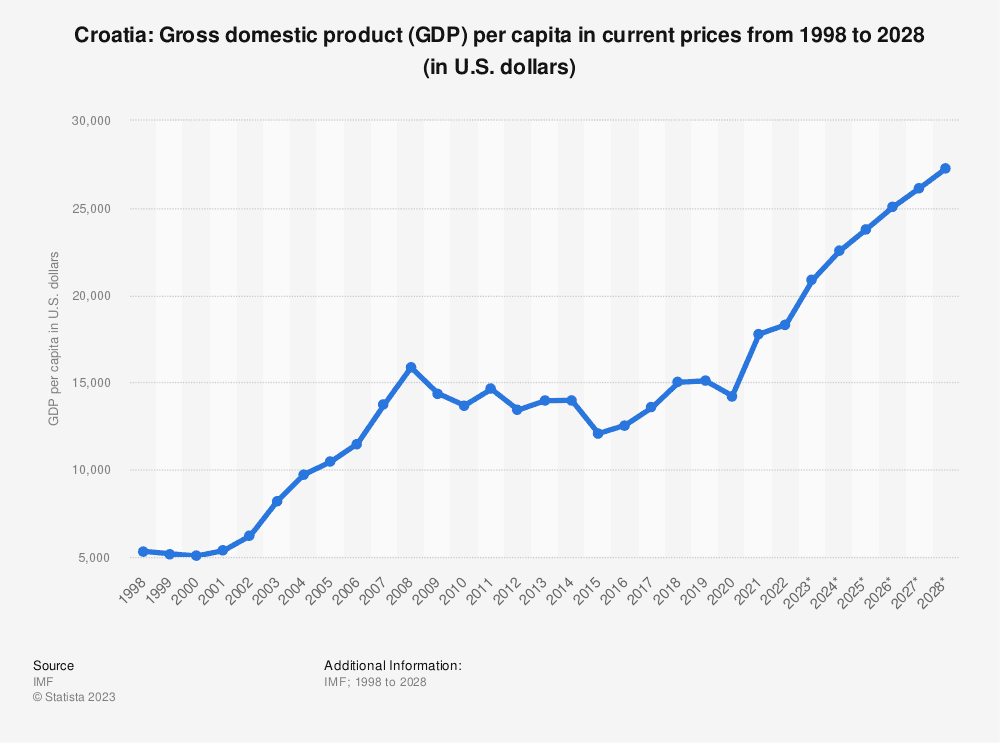

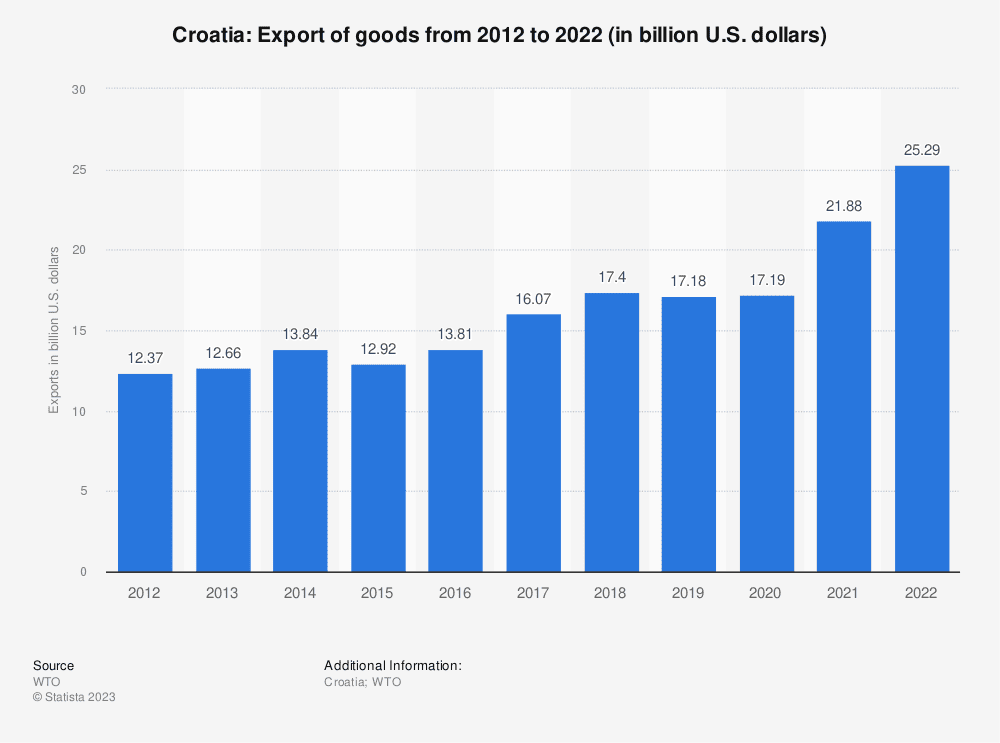

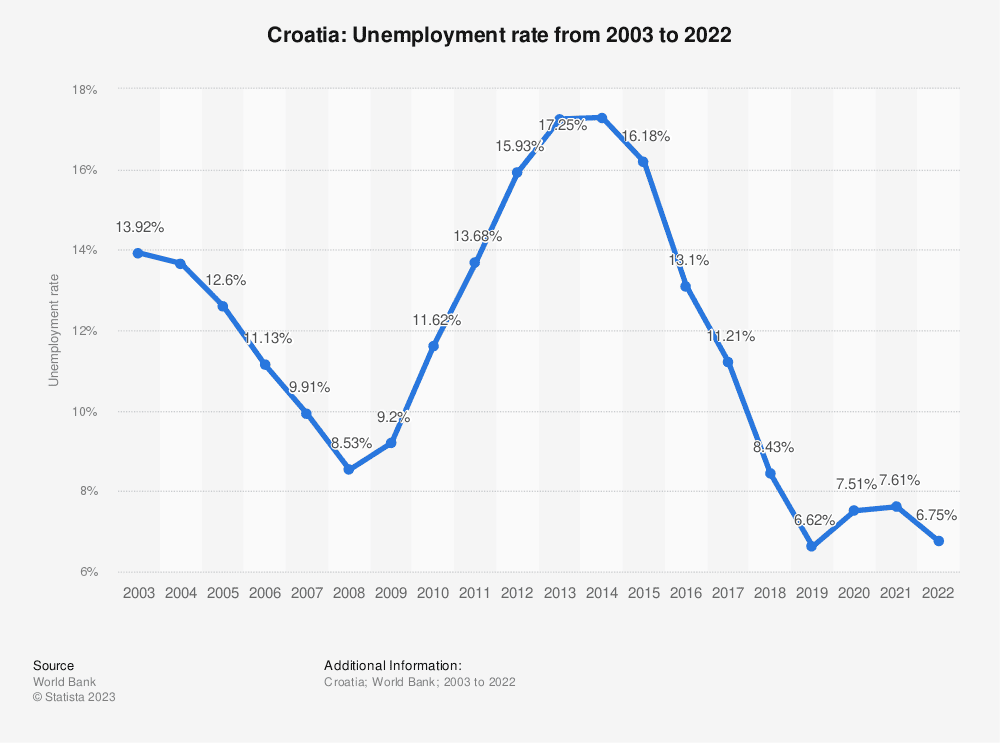

In terms of economic growth, ten years after joining the EU, per capita GDP in Croatia has increased from 50% of the EU average to 75%, managing to fully recover after the 2008 crisis; exports have doubled; and the unemployment rate has dropped from 17.25% in 2013 to 6.75%.

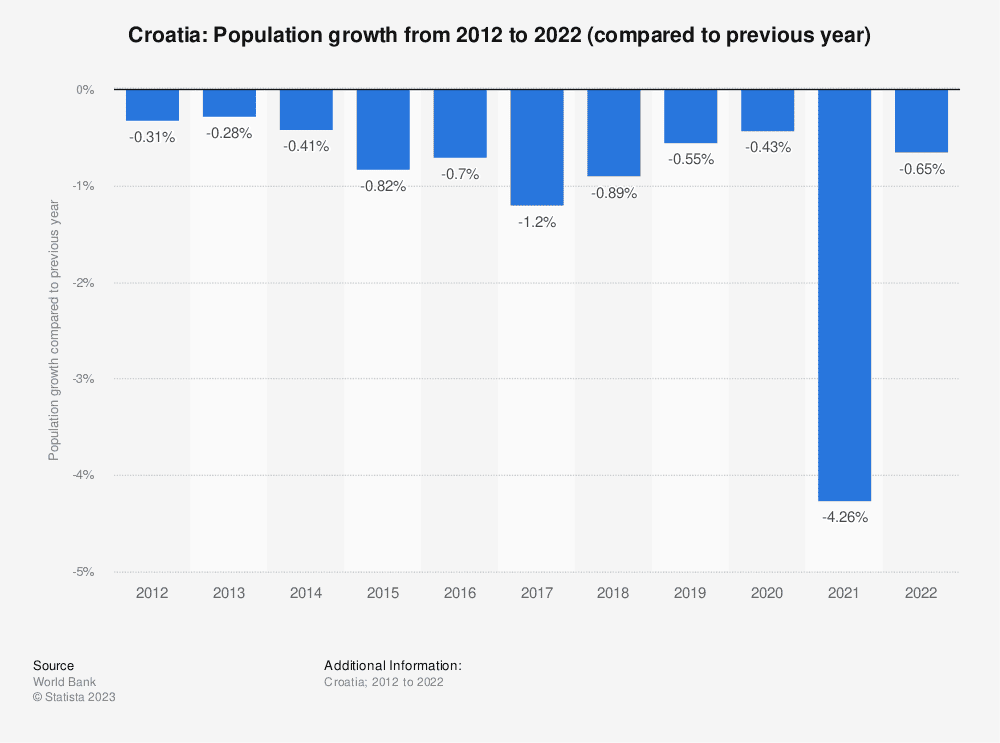

The first country of origin of foreign workers is Bosnia and Herzegovina, followed by Serbia, Nepal, North Macedonia and India. Currently in Croatia, 10% of workers come from non-EU countries. On the other hand, similar to other newly admitted member nations, Croatia has had a substantial population loss over the last decade and has produced less development than the European average. As of the 2021 census,[5] the population of Croatia stands at 3,871,833, reflecting a decrease of 413,056 individuals, or 9.64 percent, compared to the previous decade.

This is due in part to Croatia’s participation in the European Union, where worker mobility is unrestricted within the single market. In pursuit of employment opportunities and a better standard of living, a significant number of Croatian residents have relocated to wealthier member nations.

Nonetheless, this may only provide a partial explanation, given the substantial population declines observed in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia. Furthermore, Germany, which is not the only country grappling with a labour shortage, boasts over two million available positions, which could be cited as one of the reasons.

Nonetheless, this may only provide a partial explanation, given the substantial population declines observed in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia. Furthermore, Germany, which is not the only country grappling with a labour shortage, boasts over two million available positions, which could be cited as one of the reasons.

Zagreb, which is home to around 20 percent of the country’s total population, contributed 34% of the national GDP in 2018. According to the most recent report on Croatia from the European Commission,[6] Grad Zagreb (the Capital’s region) was the only Croatian NUTS to have a higher GDP per head in 2021 than the EU27 average. To prevent emigration, therefore, a more uniform development of Croatia’s regions is required.

In addition to economic growth and better crisis management, EU membership has enabled Croatia to strengthen its sense of security and self-confidence. Since becoming a full member of the EU, Croatia has been participating in decision-making processes in the EU Council on an equal footing with the other member states and is involved in all key procedures for policy-making and the passing of European laws.

Today, everyone in Croatia is aware of the great help received from the EU and most citizens consider membership to be positive. During the accession negotiations, however, not everyone was optimistic. In the referendum on Croatia’s accession to the EU, only 43% of the eligible voters had gone to the polls. Of these, 66% had voted in favour of accession.

Issues to be faced after Schengen: Relations with Belgrade and Sarajevo

The entry of the Balkan country into the Schengen area, which became official on 1 January 2023, also had repercussions on relations with neighbouring countries in the Balkan area: Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia in particular. Starting probably from November 2023, entering the Schengen area will require filling in a new online form called ETIAS (European Travel Information and Authorisation System).[7] This will cause inevitable delays in the passage of people and goods, and those who will suffer the greatest losses in terms of exports from these changes will be the two non-EU countries.

Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are also burdened, and now more heavily, with the management of the Balkan migrant route from Greece and Turkey to Europe. Zagreb has intensified controls along the crossing points, and this is all the more worrying in view of the many violent incidents that have occurred along the Serbian-Croatian border and especially between Croatia and Bosnia Herzegovina. One of the first such cases was that of Madina Hussiny, a 6-year-old Afghan girl, who in 2017, after being turned back at the Croatian-Serbian border with her family, was run over and killed by a train while walking along the tracks. The following year, the same police shot at a truck that had not stopped at the stop sign and injured nine people, including two minors. In 2020 alone, there were 16,500 mass rejections at the border that we know of.

In general, Belgrade and Sarajevo complain of worsening political and economic relations with Zagreb and this does not seem likely to improve in the near future, especially if Belgrade and Sarajevo remain outside the EU.

Their accession processes started in the same years as Croatia’s but have encountered more difficulties and are still stalled today. Bosnia and Herzegovina only achieved candidate status in December 2022, after six years of applying for membership, and now needs to implement 14 key priorities to start negotiations. Serbia, which applied for membership in December 2009 and for which negotiations began nine years ago, must resolve several issues on which Brussels has given a negative opinion. Among the most contentious issues are justice and fundamental rights, freedom, security and the environment. On the latter, Brussels’ verdict was completely negative. To these issues must be added the never-achieved resolution of the historical disputes with Kosovo.

Conclusions

Croatia is 10 years into the European Union and for the past year or so has been among the 15 countries in the world that are part of NATO, the EU, Schengen and the Euro. Looking back, the country has certainly grown economically and has been able to benefit from the economic incentives from Brussels, but Zagreb is now faced with the problems that this growth process has inevitably increased: from the relationship with the other Balkan countries, which are still outside the EU and therefore disadvantaged, to the management of migrants.

As a “good EU pupil,” Croatia has the potential to contribute positively to the overall EU enlargement process, especially in the Balkans.[8] It has been an ardent advocate for additional expansion and, using its previous experience, can offer guidance and help.

Owing to its considerable dimensions, strategic location, and robust European identity, Croatia’s integration into the European Union has deviated in several respects. However, as seen by its performance during its first decade, exceptions can occasionally be politically astute. Croatia, much like its renowned soccer squad, has been surpassing expectations in several aspects. Thus, its “success story” might serve as a model for future EU enlargements and stimulate European integration.

Sources

- https://vlada.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/2016/Glavno%20tajni%C5%A1tvo/Materijali%20za%20istaknuto/2014/CroatiaEU/Accession%20process.pdf ↑

- https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-01/cp200009en.pdf ↑

- https://dnevnievropskiservis.rs/8-eu-prioriteti/137-vesti/19193-hrvatska-je-za-10-godina-lanstva-u-eu-dobila-milijarde-evra-i-politiko-samopouzdanje ↑

- https://glashrvatske.hrt.hr/en/economy/croatia-has-made-significant-progress-in-10-years-of-eu-membership-10819549 ↑

- https://dzs.gov.hr/u-fokusu/popis-2021/popisni-upitnik/english/1361 ↑

- https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-06/ip235_en.pdf ↑

- https://www.schengenvisainfo.com/news/serbs-bosnians-will-need-an-etias-travel-authorization-to-enter-croatia-as-of-november-2023/ ↑

- https://www.blue-europe.eu/analysis-en/full-reports/the-eu-enlargement-in-the-western-balkans-new-challenges-after-the-war/ ↑