In the Blue Europe Country Dossiers, we present Central and Eastern European countries under a basical but important point of view : how their economy work. Our articles are updated yearly, for a more complete and uptodate reading. 2021 version updated by Pawel.

The education system

The Polish education system is quite similar to many European countries: after primary school, pupils go through secondary school (gimnazjum) before going on to high school (liceum), at the end of which the “matura” (an equivalent of A-levels or the baccalaureate) takes place. Compulsory education in Poland lasts 10 years and includes the last year of pre-school education, 6 years of primary school and 3 years of lower secondary school[1].

The implementation of the 2017 reform on the structure of the education system reduced the duration of compulsory education by one year. It will now last 9 years, covering the last year of pre-school education and 8 years of primary school.

Education is compulsory until the age of 18, but since this reform, it starts at age 15 instead of 16. It can be in school or through vocational training with an employer.

Pre-school education is optional for ages 3 to 5 and becomes compulsory from age 6. The 2017 reform also reduced the minimum age for a kindergarten place by 1 year, from 4 to 3 years. All 4- and 5-year-olds are entitled to a place in a kindergarten. Since the 2017 reform, this right also applies to 3-year-olds[2].

Parents of 6-year-olds can choose between sending their child to the first year of primary school or letting them stay in a kindergarten for an additional year. 7-year-olds begin compulsory education in Grade 1 of primary school.

Technical colleges are attended by ages 15 to 20. A 5-year diploma confirms vocational qualifications after passing the examination, and a secondary school leaving certificate is awarded after passing the school leaving examination.

In 2019, the pass rate for the matura (baccalaureate) was 80.5% (81.2% for girls, 79.6 for boys). 247230 participated, 199056 obtained the baccalaureate (109154 girls out of 134351 obtained it, and 89902 boys out of 112879)[3].

Higher education

For more than 60% of the population, secondary education is the highest level of education attained. However, tertiary education is increasing: in 2012, 25% of adults had a tertiary degree; this figure was of 11% in 2000. This increase can be explained by generational differences: 28% more adults aged 25-34 have studied at tertiary level than those aged 55-64[4]. This difference is the second largest among OECD countries.

Tertiary education further increases the chances of finding a job, with 85% of 25-64 year olds with tertiary education having a job compared to 66% of those with secondary education, which is also one of the largest differences among OECD countries.

The number of Erasmus students coming to Poland almost tripled between 2007 and 2014, from 4,000 to 12,000. The five universities with the highest number of Erasmus students are, in order, Warsaw, Krakow, Wroclaw and Lodz. The top five sending universities are, in order, Krakow, Warsaw, Wroclaw, Lodz and Poznan[5].

Infrastructures

As Poland suffered extensive damage during the Second World War, most of the current infrastructure was built under the People’s Republic. At the beginning of the Soviet era in Poland, Warsaw was almost completely rebuilt, and very hastily:

-In the 1960s, the school construction programme “Tysiąclatek” started[6].

-In the 1970s, concrete buildings, whose architectural style is characteristic of the whole Eastern bloc, began to be built on a large scale.

Under the mandate of the first secretary of the USSR Central Committee Edward Gierek (1970-1980), major investments were launched throughout the country. Roads, railway lines, stations, factories, factories, and flats were built[7]. These “credit” investments had on the one hand, a fundamental impact on the landscape of today’s Poland and, on the other hand, led to a long-term economic crisis, responsible for the collapse of the People’s Republic of Poland.

Contemporary investments

Although Poland chose a modern liberal turn from the 1990s onwards, characterised by a low share of the state, it has nevertheless continued to invest relatively stable in its infrastructure. In the 21st century, Polish construction has been boosted by, among other things, Euro 2012. For this event, the National Stadium in Warsaw, the modern stadiums of Gdańsk, Poznań and Wrocław, as well as several roads and hundreds of kilometres of motorways (including the one linking Germany to Warsaw[8]. Furthermore, in 2006, Poland embarked on a colossal road investment: the Polish section of the Via Carpatia linking Lithuania to Greece[9].

The central communication port

The Solidarity Transport Hub is a project which consists of combining air, rail and road transport between Warsaw and Lodz. Train transport from the new central airport will take only 15 minutes to Warsaw, 25 minutes to Lodz, and 2 hours to Poznan, Krakow and Gdansk. The hub is expected to serve around 45 million passengers a year and the first plane is scheduled to take off during the winter season 2027/2028[10].

Expressways

There are two types of expressways in Poland: motorways and expressways. The differences between them are very subtle and mainly concern details such as the maximum length of the arch, the width of the hard shoulder etc[11]. In Poland, some motorways are managed by concessionaires. Toll prices on these “private” motorways are much higher than on those managed by the State.

In the World Economic Forum’s 2020 report, Polish roads were ranked 20th in Europe and 57th in the world. Documentation on the condition of the most important Polish roads can be found on the website of the General Directorate of National Roads and Motorways: www.gddkia.gov.pl/mapa-stanu-budowy-drog_wielkopolskie.

Polish sea transport

Four Polish cities (Gdańsk, Szczecin, Gdynia and Świnoujście) have particularly strategic ports for the Polish economy[12]. In a number of small towns there are loading ports, among others at Elbląg, Kołobrzeg, Ustka and Władysławowo.

Poland has as a major project the Vistula Crossing to build a navigation channel. The investment aims to shorten the existing road between the Vistula lagoon and the waters of the Baltic Sea by 100 km and, above all, to make it completely independent of Russia. The investment is criticised for its enormous costs and great environmental damage.

Rail transporters in Poland

The State Treasury is mainly responsible for rail transport in Poland. Two major national companies stand out from the rest of the country: Polregio (formerly called Regional Transport) – which mainly operates regional links – and PKP Intercity, which provides fast, long-distance and international connections.

The other companies are carriers operating mainly within the borders of the provinces and their surroundings. They include, among others, Wielkopolska Railways, Warsaw Suburban Railways and Urban Rapid Railways.

Polish Airlines

The national air carrier in Poland is Polish Airlines (LOT), but there are also several small private companies operating alongside it. LOT Polish Airlines has 90 aircraft, and in 2019 it carried around 10 million passengers[13]. Although it occupies an average position among the world’s airlines, it is one of the oldest in the world (92 years of operation).

Geography

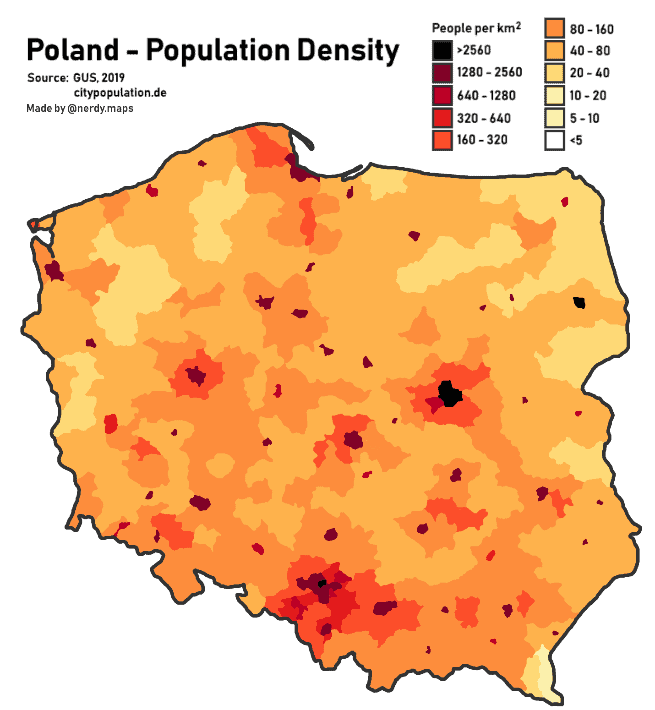

There are wide disparities between the east and west of Poland. While the regions west of the Vistula are particularly developed and economically attractive, the Vistula is struggling to keep up and is being emptied of its young population, which prefers to move to cities in western Poland or even the European Union in search of better universities and economic opportunities. Despite this, the population density remains more or less homogenous across the country to date (Fig. 1).

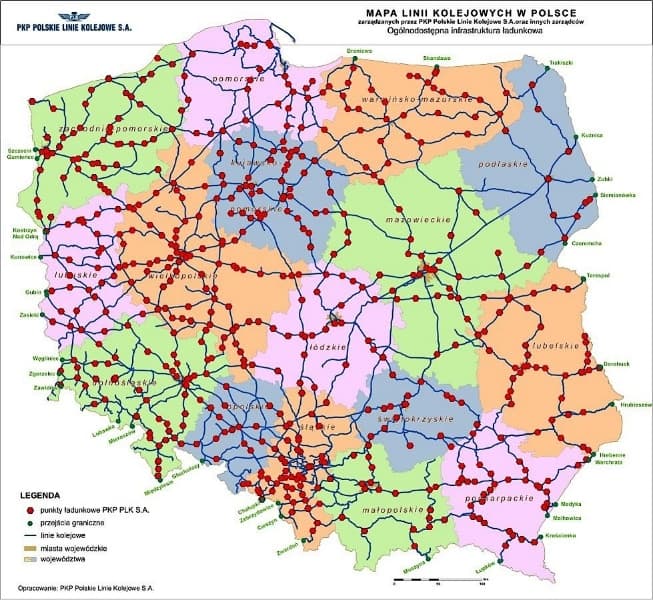

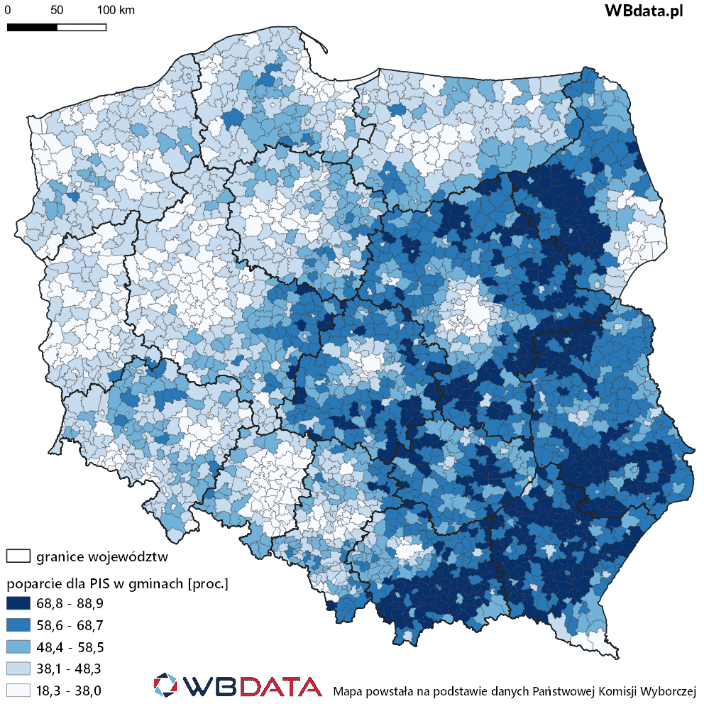

The economic disparity between west and east is particularly visible in terms of infrastructure: the railways are much more developed and modern in the west (Fig. 2). It also manifests itself politically: while the west is a stronghold of the citizens’ platform – rather liberal and pro-EU – eastern Poland votes overwhelmingly for the PiS, a party with Eurosceptic and conservative tendencies (Fig. 3).

Fig 1, population density in Poland

Source: GUS

Fig. 2, Map of railways in Poland

Source: płk-sa.pl

Fig 3, Polish parliamentary elections of 2019

Source: wbdata.pl

The internal population movement is increasing every year, however, the majority of Poles remain attached to their region, and young people prefer to live with their parents. According to Eurostat, in 2014, 76.7% of young Poles (18-35 years old) were living with their parents. This figure is well above the European average (66%). Furthermore, according to Eurostat, between 2007 and 2017, the percentage of the urban population remained relatively stable and even decreased (from 61% in 2007 to 60% in 2017).

Poland has the 6th largest economy in the European Union with a GDP of 532 billion euros in 2019. Its economy has been growing steadily since the liberalisation of its economy in 1990 and is not experiencing the crisis: it was spared from the subprime crisis of 2008. While Europe endured a 4.5% recession, Poland recorded growth of 1.9%.

The sector that contributes the most to Polish GDP is services (57%). It is followed by industry (29%) and agriculture (2%). Poland exports a value of 259M dollars per year, mainly to Germany[14]. Its main export sectors are those of machine tools for transport/logistics. Poland imports a value of $278M (a deficit of $19M), mainly from Germany. The main sectors for imports[15] are the same as for exports.

Women and families

Since 1989, Poland has been one of the European countries with the lowest fertility rates. Indeed, Polish women will have about 1.36 children per woman in 2018 and a fertility rate close to 9.3%[16]. As a result, the country is experiencing a clear demographic slowdown. The main cause of this demographic slowdown is primarily social. Indeed, during the 1990s and 2000s, the country witnessed an increase in job insecurity (in 2004, 20% of the Polish population was unemployed, compared with 3.92% in 2019) combined with wages that were often below the European average. According to Eurostat, Polish women have on average their first child around the age of 26, more than one below the European average of 28.

Family allowances

In 2017, a family allowance of 500 zlotys (called 500+) has been introduced to encourage the birth rate. This allowance can only be received from the second child onwards, regardless of the family’s income. This initiative by the ruling political party PIS to remedy the low birth rate has found its place in Polish mentalities[17]. In addition, there are other family benefits[18]:

- -family allowance with supplements (covering part of the subsistence expenses of the family)

- -birth grant (paid in respect of the birth of a living child)

- -parental allowance (paid for the birth of a child)

- -Child Rearing Benefit (paid to parents or guardians of children up to the age of 18)

- -The single premium granted under the “For Life” law for pregnant women and their families (for a child with a disability or an incurable fatal disease of origin, etc.) is a one-off payment.

- -An additional bonus paid once a year for each new school year until the age of 20.

In order to be eligible for these benefits, a family’s resources must not exceed 674 zlotys per person in the family[19]. With regard to childcare facilities, it should be noted that in Poland only 2% of children can find a place in a nursery. This low rate can be explained as follows: Polish families prefer private childcare, i.e. the family as the main place of socialisation, rather than extra-familial childcare, which is why the majority of Polish children are in their earliest years cared for by the mother, grandmother or in some cases by a person at home. In Poland, nursery care is therefore seen as a solution of last resort.

In Poland, the family is seen as one of the most important goals in life among all social classes. Moreover, the woman in Polish society is generally keen to interrupt her professional activity to take care of her young children. This view of women is known in Poland as Matka-Polka. Maternity leave in Poland for women is approximately between six months and one year.

According to the EURES agency, women are more affected by unemployment than men with a rate of 11.1% in 2018 compared to 9.8% for men in 2013. Part-time work is less prevalent in Central and Eastern European countries as it affects only 9.8% of the working population in this geographical area. While in Western Europe the feminisation of part-time work is largely dominant, this is not the case in Poland. Women account for 58.2% of the working population in Poland and only 13.7% worked part-time in 2003[20]. Part-time work is therefore not a discriminating factor for women in the labour market. Moreover, it is important to stress the fact that part-time work is above all over-represented by the young and the elderly. Moreover, in Poland, it can be seen that more women graduate more from higher education (30.1% for women compared to 20.3% for men[21]). It is also interesting to note that the gender pay gap in Poland is 7% (compared to 15% in France) and 79% of women participate in the labour market compared to 90.8% of men[22]. These figures are in line with the European average which is 79.6% for women against 91% for men.

Private property in Poland

Today, the five largest Polish companies listed on the stock exchange are companies owned or controlled by the State Treasury[23]. Nevertheless, every day about 1000 new private companies are created in Poland. Poles, having seen their standard of living rise considerably since 1990, are consuming more (especially in private SMEs) and are making increasing use of services (private insurance, transport, entertainment etc.).

Corruption in Poland

In the Corruption Investigator Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, Poland, with 60 points, is ranked 35th out of 180 countries in the list[24]. Behind Poland are, among others, the following countries: Czech Republic, Latvia and Italy.

Polish law generally provides for a maximum sentence of 8 or 10 years imprisonment for corruption offences[25]. The fight against corruption is carried out by a special service – the Central Anti-Corruption Bureau.

The housing market and loans

The Polish real estate market is developing dynamically. Dozens of new buildings are under construction. In 2019, the number of new flats completed exceeded 200,000. Many young people, both married and unmarried, are turning to buying flats on credit. According to statistics, in 2018, almost 4 million people in Poland paid back a housing loan[26].

Due to the high cost of housing, it is not uncommon for young people to stay late at home with their parents, as well as for young couples who have found it difficult to become homeowners.

Agriculture – how many farms are there in Poland?

According to the Central Statistical Office, in 2018 there were about 1.4 million farms in Poland. These farms occupied 14.7 million hectares of agricultural land and raised almost 10 million animals. Polish farmers often benefit from development opportunities thanks to the many EU subsidies and support programmes for farmers.

The north and west of the country have the highest number of hectares of land per farm, ranging from 23 to 28 hectares. The situation is different in the south and east, where farms average between 4 and 6 hectares.

Social mobility. Is it possible to become rich in Poland?

A few years ago, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development published a report on social mobility in the world. The very title of the document – “A Broken Social Elevator” – does not give cause for optimism. It is also discouraging that, according to OECD experts, the son of a physical worker in Poland has only a 25 per cent chance of promotion on the social ladder. The OECD highlights phenomena such as the “sticky floor” that prevents social promotion and the “sticky ceiling” that prevents the rich from losing their assets. However, it should be mentioned that despite these difficulties, hundreds of new companies are registered every day in Poland.

Poland’s deficit

The vast majority of the state budget is spent on pensions, invalidity and other social insurance benefits (in 2018, around 269 billion, or 30% of total expenditure). A significant part of the budget is also spent on health care and infrastructure development. Interestingly, Poland’s environmental expenditure (of around PLN 23 billion) represents only 3% of the total.

According to the report of the Republican Foundation, in 2018 the public finance deficit amounted to PLN 61.4 billion with revenues of PLN 829.6 billion and expenditures of PLN 891 billion[27]. The Polish Civic Development Forum has provided an accurate counter of public expenditure, available at www.dlugpubliczny.org.pl. For many years, the FOR’s public debt counter has been displayed in one of the main streets of Warsaw.

What taxes are paid in Poland?

The Polish tax system does not differ much from that of Western European countries. Poles mainly have to pay the following taxes:

-Income taxes (PIT for individuals and CIT for entrepreneurs)

-Indirect taxes : VAT and excise duties

-Taxes on real estate, inheritance and donations, civil law transactions, gambling and capital gains

Polish Diaspora

The Polish diaspora, also known as “Polonia” commonly designates first generation Polish emigrants (expatriates mainly during the 1920s-30s) as well as their descendants. It would count around 20 million members to its credit. The term Polonia was first used in 1875 in the United States. Originally, the main purpose of “Polonia” was to remind Polish emigrants of their ties with their country of origin and thus of their obligations towards it, especially their political obligations. In the spirit of Polonia, every emigrant had to work for the effort of the return of the country’s independence.

The współnota Polska (“the Polish Community”) is an international non-governmental organisation which was established in February 1990 on the initiative of the Polish Senate. Its aim is above all to strengthen the links between the Polish diaspora and Poland, as shown by its statutes in 2008 “the Association aims to strengthen the links between Polonia and the homeland, language and culture and to help meet the various needs of our compatriots throughout the world […] convinced of the integrity of Polish culture, the common destiny of the Polish community and the need for solidarity in the preservation of the national identity; it is necessary to] take measures for the renown of Poland and Poles, regardless of their degree of integration in the country of residence”[28].

Among the founders and members of the association are people who are highly placed in the state hierarchy, such as senators and deputies, independence activists or representatives of different religious cults such as the Roman Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant churches, and intellectual elites.

Bibliography

1958-1965 – Akcja “1000 Szkół na Tysiąclecie Państwa Polskiego”. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://fotopolska.eu/Polska/b49943,1958-1965_-_Akcja_1000_szkol_na_Tysiaclecie_Panstwa_Polskiego.html

A3, E. (2020, January 28). Poland – ERASMUS+ 2018 in numbers. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/resources/documents/poland-erasmus-2018-numbers_en

Antykorupcyjne, C. (n.d.). Konsekwencje korupcji. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.antykorupcja.gov.pl/ak/archiwum-mswia/poradnik-antykorupcyjn/konsekwencje-korupcji/64,Konsekwencje-korupcji.html

Biuletyn informacji PUBLICZNEJ Miasta POZNANIA BETA. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://bip.poznan.pl/bip/sprawy/wspieranie-rodziny-zasilek-rodzinny-od-01-11-2020-do-31-10-2021,101/

Dagmara Marszałek dagmara.marszalek@totalmoney.pl artykuły tego autora, Marszałek, D., Dagmara.marszalek@totalmoney.pl, & Autora, A. (n.d.). Zadłużenie Polaków W Bankach w 2020 Roku – sprawdź strukturę i statystyki Długów POLSKICH kredytobiorców. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.totalmoney.pl/artykuly/zadluzenie-polakow-w-bankach-w-2020-roku-sprawdz-strukture-i-statystyki-dlugow-polskich-kredytobiorcow

Flota. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://corporate.lot.com/pl/pl/nasza-flota

Gus. (2020, June 05). Liczba osób, które przystąpiły/zdały egzamin maturalny. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/edukacja/edukacja/liczba-osob-ktore-przystapilyzdaly-egzamin-maturalny,15,1.html

Le Marché polonais : Principaux secteurs. (n.d.). Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://import-export.societegenerale.fr/fr/fiche-pays/pologne/marche-principaux-secteurs

Le système éducatif polonais. (2017). Délégation Académique Aux Relations Européennes, Internationales Et De Coopération DAREIC, Démarche académique d’échange d’expertises éducatives européennes, 5.

Mojeauto.PL. (n.d.). Czym się Różni droga Ekspresowa od autostrady? Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://motogazeta.mojeauto.pl/Polskie_drogi/Czym_sie_rozni_droga_ekspresowa_od_autostrady,a,224291.html

Największe firmy w Polsce – ranking. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.nntfi.pl/finanse-po-godzinach/najwieksze-firmy

Pologne – Indice de perception de LA corruption 2018. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://fr.countryeconomy.com/gouvernement/indice-perception-corruption/pologne

Pologne – pib – Produit INTÉRIEUR BRUT 2020. (n.d.). Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://fr.countryeconomy.com/gouvernement/pib/pologne

Port solidarność. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.cpk.pl/pl/inwestycja/lotnisko

Report: The percentage of poles with higher education is close to the OECD average – Ministry of science and higher education – GOV.PL WEBSITE. (2019, September 26). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.gov.pl/web/science/report-the-percentage-of-poles-with-higher-education-is-close-to-the-oecd-average

Rodzi się więcej dzieci. współczynnik Dzietności Wzrósł do 1,45. (2018, May 23). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.bankier.pl/wiadomosc/Rodzi-sie-wiecej-dzieci-Wspolczynnik-dzietnosci-wzrosl-do-1-45-4119437.html

Rodzina 500 plus – Ministerstwo Rodziny I POLITYKI Społecznej – Portal Gov.pl. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/rodzina-500-plus

Rogojsz, Ł. (2012, July 03). „Newsweek” PRZEDSTAWIA POLSKIE ARENY Euro 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.newsweek.pl/euro-2012-stadiony-poznan-gdansk-warszawa-wroclaw-polska-futbol/6188dbk

Szacunek 2018 – Ministerstwo Finansów – Portal Gov.pl. (n.d.). Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/szacunek-2018

Szlak Transportowy Via carpatia. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.mbpr.pl/vc.html

Wielka EMIGRACJA: France Pologne – FRANCJA Polska: Patrimoines Partagés. (n.d.). Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://heritage.bnf.fr/france-pologne/pl/wielka-emigracja-art

Wielkie inwestycje dekady Gierka. HUTA Katowice, RAFINERIA Gdańska, FSM… [top]: Historia.org.pl – historia, kultura, muzea, matura, rekonstrukcje i Recenzje historyczne. (2013, January 05). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://historia.org.pl/2013/01/05/sukcesy-inwestycyjne-dekady-gierka-huta-katowice-rafineria-gdanska-fsm/

Zasiłek rodzinny – Ministerstwo Rodziny I POLITYKI Społecznej – Portal Gov.pl. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/zasilek-rodzinny

- Le système éducatif polonais. (2017). Délégation Académique Aux Relations Européennes, Internationales Et De Coopération DAREIC, Démarche académique d’échange d’expertises éducatives européennes, 5. ↑

- Le système éducatif polonais. (2017). Délégation Académique Aux Relations Européennes, Internationales Et De Coopération DAREIC, Démarche académique d’échange d’expertises éducatives européennes, 5. ↑

- Gus. (2020, June 05). Liczba osób, które przystąpiły/zdały egzamin maturalny. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/edukacja/edukacja/liczba-osob-ktore-przystapilyzdaly-egzamin-maturalny,15,1.html ↑

- Report: The percentage of poles with higher education is close to the OECD average – Ministry of science and higher education – GOV.PL WEBSITE. (2019, September 26). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.gov.pl/web/science/report-the-percentage-of-poles-with-higher-education-is-close-to-the-oecd-average ↑

- A3, E. (2020, January 28). Poland – ERASMUS+ 2018 in numbers. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/resources/documents/poland-erasmus-2018-numbers_en ↑

- 1958-1965 – Akcja “1000 Szkół na Tysiąclecie Państwa Polskiego”. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://fotopolska.eu/Polska/b49943,1958-1965_-_Akcja_1000_szkol_na_Tysiaclecie_Panstwa_Polskiego.html ↑

- Wielkie inwestycje dekady Gierka. HUTA Katowice, RAFINERIA Gdańska, FSM… [top]: Historia.org.pl – historia, kultura, muzea, matura, rekonstrukcje i Recenzje historyczne. (2013, January 05). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://historia.org.pl/2013/01/05/sukcesy-inwestycyjne-dekady-gierka-huta-katowice-rafineria-gdanska-fsm/ ↑

- Rogojsz, Ł. (2012, July 03). „Newsweek” PRZEDSTAWIA POLSKIE ARENY Euro 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.newsweek.pl/euro-2012-stadiony-poznan-gdansk-warszawa-wroclaw-polska-futbol/6188dbk ↑

- Rogojsz, Ł. (2012, July 03). „Newsweek” PRZEDSTAWIA POLSKIE ARENY Euro 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.newsweek.pl/euro-2012-stadiony-poznan-gdansk-warszawa-wroclaw-polska-futbol/6188dbk ↑

- Port solidarność. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.cpk.pl/pl/inwestycja/lotnisko ↑

- Mojeauto.PL. (n.d.). Czym się Różni droga Ekspresowa od autostrady? Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://motogazeta.mojeauto.pl/Polskie_drogi/Czym_sie_rozni_droga_ekspresowa_od_autostrady,a,224291.html ↑

- Hanna Klimek. Strategia rozwoju polskich portów morskich. (2015). Studia Gdańskie, t. V, 225–244. ↑

- Flota. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://corporate.lot.com/pl/pl/nasza-flota ↑

- Le Marché polonais : Principaux secteurs. (n.d.). Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://import-export.societegenerale.fr/fr/fiche-pays/pologne/marche-principaux-secteurs ↑

- Le Marché polonais : Principaux secteurs. (n.d.). Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://import-export.societegenerale.fr/fr/fiche-pays/pologne/marche-principaux-secteurs ↑

- Rodzi się więcej dzieci. współczynnik Dzietności Wzrósł do 1,45. (2018, May 23). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.bankier.pl/wiadomosc/Rodzi-sie-wiecej-dzieci-Wspolczynnik-dzietnosci-wzrosl-do-1-45-4119437.html ↑

- Rodzina 500 plus – Ministerstwo Rodziny I POLITYKI Społecznej – Portal Gov.pl. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/rodzina-500-plus ↑

- Zasiłek rodzinny – Ministerstwo Rodziny I POLITYKI Społecznej – Portal Gov.pl. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/zasilek-rodzinny ↑

- Biuletyn informacji PUBLICZNEJ Miasta POZNANIA BETA. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://bip.poznan.pl/bip/sprawy/wspieranie-rodziny-zasilek-rodzinny-od-01-11-2020-do-31-10-2021,101/ ↑

- Kobiety I mezczyzni na rynku pracy. Glowny Urzad Statystyczny. 2014. ↑

- Kobiety I mezczyzni na rynku pracy. Glowny Urzad Statystyczny. 2014. ↑

- Kobiety I mezczyzni na rynku pracy. Glowny Urzad Statystyczny. 2014. ↑

- Największe firmy w Polsce – ranking. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.nntfi.pl/finanse-po-godzinach/najwieksze-firmy ↑

- Pologne – Indice de perception de LA corruption 2018. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://fr.countryeconomy.com/gouvernement/indice-perception-corruption/pologne ↑

- Antykorupcyjne, C. (n.d.). Konsekwencje korupcji. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.antykorupcja.gov.pl/ak/archiwum-mswia/poradnik-antykorupcyjn/konsekwencje-korupcji/64,Konsekwencje-korupcji.html ↑

- Marszałek, D. Zadłużenie Polaków W Bankach w 2020 Roku – sprawdź strukturę i statystyki Długów POLSKICH kredytobiorców. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.totalmoney.pl/artykuly/zadluzenie-polakow-w-bankach-w-2020-roku-sprawdz-strukture-i-statystyki-dlugow-polskich-kredytobiorcow ↑

- Szacunek 2018 – Ministerstwo Finansów – Portal Gov.pl. (n.d.). Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/szacunek-2018 ↑

- Voldoire, J. (2017, December 01). Enjeux de POUVOIR, ENJEUX de reconnaissance ou L’ethnicisation de l… Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://journals.openedition.org/remi/7479?lang=es ↑