1.Introduction

“Geography has always been a kind of prison. A prison that dictates what a country is or can be.”[1]

This is a quote from Tim Marshall’s book “Prisoners of Geography,” in which the author emphasizes the crucial role of geography on the history of individual states, comparing it to a prison from which there is no escape. Throughout history, it is geography-as the foundation of reality-that has determined the location of cities, the directions of trade routes, or the directions of migration, thus determining the framework for the development of intercultural and political contacts.

Speaking of geography as a factor influencing the fate of a country, it is worth noting that just as a country does not decide what rivers flow through it, neither does it influence with whom it shares borders. Both terrain and geopolitical neighbourhoods are imposed by nature and history – and countries must learn to function within this framework.

There is no doubt that European history is largely a history of wars. Over the centuries, various European countries have fought numerous wars against each other, which not only shaped the borders and fates of nations but also left a lasting mark in the collective memory, thus making cooperation between conflicting nations more difficult.

After the end of World War 2, the societies of Western Europe attempted to establish economic cooperation with the primary aim of preventing a similar conflict in the future. Thus, in 1951, the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was established, which in the future transformed into the European Union we know today.

The sentiment circulating around European integration at the time is well captured by the so-called “Schuman Declaration,” in which French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman stated that through efforts at integration “[…] simply and quickly, the fusion of interests necessary for the establishment of an economic community will take place and the leaven of a broader and deeper community of countries long divided by bloody conflicts will be introduced […].”[2]

The modern European Union has 27 countries. Its biggest expansion took place in 2004, when as many as 10 countries joined the community. This group also included Poland, which, by virtue of its place on the map, had to establish close cooperation with Germany – its western neighbour, which is, on the one hand, a wealthy and historical member of the European Union, as well as an advocate of its enlargement to include the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Nevertheless, Germany has left a deep scar in the collective memory of the citizens of Central and Eastern Europe, especially Poles, given the crimes committed in occupied Polish territory during World War II.

The purpose of this paper is to show contemporary Polish-German relations in a broader context, considering the Polish perspective, examining what factors shape the image of Germany in the eyes of Polish public opinion and how this image translates into Polish policy towards Germany. To do so, we will trace the most important historical processes in Polish-German relations, with a particular focus on the World War 2 and post-war periods, focusing on the so-called “policy of reconciliation,” i.e. actions aimed at overcoming historical burdens and rebuilding mutual trust, necessary for cooperation in the framework of allied relations in Western security structures. We will then focus on the economic relationship between Germany and Poland, showing the deep interdependence linking the two countries. The next part of the paper will include an analysis of Polish public opinion surveys on German politics and society. We will examine, using the topic of war reparations as an example, how the attitude of Polish public opinion toward Germany can benefit Polish domestic and foreign policy. Finally, we will look at the “Polish-German Action Plan,” an agreement that best illustrates the current relationship between Poland and Germany.

2. A complex history

Polish-German relations have a history of more than a thousand years. As their formal beginning, we can consider the second half of the 10th century, in which a form of the Polish state, through Christianization, was established in a political sense and was recognized by other Christian countries, including Germany,[3] as part of the Christian community. At the turn of the century, Poland and Germany, like all European countries, fought numerous wars or, depending on the situation, formed alliances. Although the Christian religion and dependence on the papacy united the two countries, there were distinct differences between them, especially on the cultural level. The Polish-German border was not only a state border, but also the border of two great ethnic groups: Slavs and Germans. However, this was not an unprecedented situation in Europe, which has always been a cultural melting pot in which numerous ethnic groups clashed. The differences between Poland and Germany, began to become more pronounced in later centuries, when Western and Eastern Europe adopted different development models.

According to Immanuel Wallernstein, the division of Europe into Western and Eastern became particularly evident in the 16th century, with the increased intensification of trade and the birth of the system we now call capitalist. Europe then began to function as a single economic organism with clearly defined differences between the west and east of the continent. Industry and trade became increasingly important in the western part of Europe, while the east concentrated on the production of raw materials and food for export, adapting its economic model to the needs of developing Western markets.[4] Because of the asymmetrical economic relationship, Immanuel Wallerstein referred to the most developed countries in Western Europe – including Germany – as “the centre,” while he categorized countries east of the Elbe – including Poland – as “the periphery.”[5]

Paradoxically, the 16th century is also referred to in Polish historiography as the “Golden Age,” during which the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was a key player on the European stage and achieved numerous economic, political, cultural, and military successes, expanding its territory to nearly one million square kilometres. Why, then, does Wallerstein identify the 16th century as the point at which Poland became a “periphery”? Wallerstein’s theories focus primarily on the economic position of states within the world-system framework. At that time, the Polish economy was based largely on a grain monoculture. Vast landed estates generated profits primarily for a narrow group of the wealthiest nobility, and – most crucially in this example – for Dutch merchants, who purchased cheap grain in Polish ports and traded it across the continent. The profits earned by the nobility through grain trade were largely spent on luxury goods that were more complex in production and manufactured in the western part of Europe. While in the short term this model, fuelled by favourable grain market conditions, provided Poland with relative stability and a period of success, in the longer term, it hindered the development of modern industry and innovation. This was due to the fact that a significant portion of Poland’s labour force was concentrated in low-skilled agricultural work.

The culmination of Poland’s adoption of a resource-based economic model with a low level of specialization came at the end of the 18th century, when the relatively small but modern German state of Prussia, together with Austria and Russia, partitioned Poland, taking advantage of its weakness and depriving Poland of statehood for 123 years. This means that in the 19th century Poland, unlike Germany, did not exist as an independent and sovereign state. It is worth noting that it was during this period that the concept of the nation-state was formed, a model that forms the basis of the modern political order.[6]

In Germany, modern national identity was expressed through the unification of the shattered states under the leadership of Bismarck in 1871 and the rapid rise to the role of a European power-country “center.” In Poland, the process was different – without its own state, under the rule of partitioners, including the Germans, the Polish lands became the “periphery” of foreign powers. Polishness was formed in opposition to their actions, such as the prohibition of the Polish language and the suppression of national traditions. In the collective memory of Poles, this time is also special because of its literary legacy. The 19th century saw some of the most important works of Polish literature, often created in exile, which addressed issues of national identity and resistance to the partitioners. Thus, it can be considered that “the struggle to preserve language, culture and identity in the face of partition and occupation became the core of Polish identity.”[7]

In 1918, after Germany lost World War 1, Poland regained its independence. It based its borders on lands historically associated with Poland, that is, also those lands that had been within the borders of the German Reich before 1918. Social discontent in Germany, a consequence of the country’s difficult internal situation and the territorial losses suffered in World War I, created favourable conditions for the emergence of Nationalism and the Nazi seizure of power, which culminated in the outbreak of World War II. During this harsh period of time, Germany committed numerous crimes against Polish citizens during the occupation, strengthening hostility towards Germans in Poland.

To summarize, throughout history, Polish-German relations have significantly deviated from being described as “friendly.” Cultural differences, different developments, as well as Germany’s apparent political and military superiority over Poland in recent centuries, mean that Polish-German relations have often been marked by tension, rivalry and distrust, leaving a lasting mark on collective memory

3. Reconciliation policy

After the end of World War 2 and the collapse of the Third Reich, two German states were created: Democratic West Germany (West Germany), and Communist East Germany, which was dependent on the USSR. While, at least in theory, East Germany became an ally of Poland, which, like East Germany, found itself in the USSR’s orbit of influence, Poland’s relations with West Germany remained undefined for many years after the war.

The main bone of contention between the post-war Polish government and West Germany remained the question of the two countries’ post-war borders. As a result of the Allied conference in Potsdam in 1945, it was decided that Poland would lose some of its pre-war territories in the east to the Soviet Union, receiving in return areas in the west that had belonged to Germany before the war. Although Poland did not formally border West Germany, with East Germany between the two countries, it is worth remembering that West Germany felt partly responsible for the fate of all Germans and also did not rule out the possibility of reunification with East Germany in the distant future, which would have meant shared borders between West Germany and Poland. In addition, West German attitudes toward western Polish lands were influenced by political pressure from West German citizens who had lived in western Polish lands before the war and who hoped that they would still return to the territories they were forced to leave after the war. The lack of agreement between Poland and West Germany on the issue of new borders was to the advantage of the USSR, which positioned itself as the guarantor of the inviolability of Poland’s western border and which exploited Polish-German antagonism to strengthen its influence in Poland. Similar anti-German rhetoric was also used by the Communists in power in Poland at the time, who emphasized the momentous role of the Polish People’s Army in the victory over National-socialism and Fascism.[8]

The breakthrough in post-war relations between Poland and West Germany was the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries in 1970, as well as the recognition by the West German government of Poland’s new borders. In the same year, then-German Chancellor Willy Brandt, during a diplomatic visit to Poland, knelt in front of the Monument to the Heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto, which symbolically signified a show of remorse and a desire for reconciliation between West Germany and Poland.

Polish-German relations took on a new dynamic after the end of the Cold War and the reshuffling of the balance of power in Europe. Independent of the USSR, democratic Poland was able to discuss with Germany on partnership terms for the first time since the end of World War 2.[9] Poland’s goal after the Cold War was to join the European Union and NATO; Germany’s goal was to increase security in the region and develop trade with Poland. Not surprisingly, Germany was the main proponent of Poland joining Western security structures and supported Poland diplomatically in this endeavour. At the time, the factors encouraging the reconciliation process were the opening of borders and the intensification of intellectual exchanges between representatives of various spheres of public life – politics, culture and the economy – as well as the establishment of joint institutions and organizations.[10]

This situation continues today, and Poland and Germany, through membership in the European Union and NATO, are important strategic partners for each other. In the next part of the analysis, we will examine the current economic interdependencies between Poland and Germany.

4. The value of trade and FDIs

The impact of Poland’s decision to join the European Union and its turn to the West is today well-represented by its trade volume with Germany. According to data published by the Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis), trade between Germany and Poland was worth 170.3 billion euros in 2024. Poland ranked fourth among the largest markets for German goods – the value of German exports to Poland reached 92.9 billion euros, placing Poland behind the Netherlands (109.2 billion) and ahead of China (89.9 billion euros). In terms of imports, Poland was also Germany’s fourth most important partner – Germany imported goods worth 77.3 billion euros from Poland, placing Poland between Italy (67.3 billion euros) and the United States (91.5 billion euros). If we look at German data in percentage terms, we find that Poland accounted for 6% of all German exports, as well as 6% of imports to Germany.[11]

If we look at Polish data from the Central Statistical Office (CSO) in 2024 on Poland’s most important trading partners, we find that Germany is both the most important market for Poland, accounting for 27.1% (94.8 billion euros) of Polish exports, as well as the most important supplier of goods accounting for 19.2% (62.2 billion euros) of Polish imports. In comparison, the second most important market for Poland in 2024, were ex aequo 2 countries – the Czech Republic and France. Poland exported goods worth 21.4 billion euros to the Czech Republic, and goods worth 21.3 billion euros to France. Both values amount to a rounded 6.1% of the value of Polish exports in 2024. This means that the sum of Polish exports to France and the Czech Republic in 2024, the second and third largest markets for Poland, is significantly behind the sum of Polish exports to Germany alone.[12]

Analysing this data, we can come to the preliminary conclusion that the Polish economy is more dependent on the German economy than vice versa. For a more complete picture, it is worth looking at data on the value of cumulative foreign direct investment (FDI stock) of German capital in Poland and Polish capital in Germany. According to Deutsche Bank, Polish cumulative FDI in Germany in 2022 amounted to €1.27 billion.[13] On the other hand, according to the National Bank of Poland (NBP), German FDI in Poland in the same year amounted to 42.6 billion euros.[14]

The disparity in FDI between Poland and Germany, is due to the different potentials of the two countries. Germany’s nominal GDP is about $4.5 trillion, while Poland’s is $809 billion. This means that Germany’s economy is approximately 5.5 times larger than Poland’s.

5. Polish public opinion about Germany

The previous part of the article outlined the historical context of Polish-German relations, as well as the current state of mutual relations between Poland and Germany-economic interdependence and strategic partnership, resulting from membership in Western socio-economic-security structures. This section analyses contemporary surveys of Polish public opinion on Germany, created by the Poland-Germany Barometer, focusing on Poles’ associations with Germany, Poles’ awareness of the relationship between Poland and Germany, and Polish public opinion’s assessment of the main factors influencing relations with Germany.

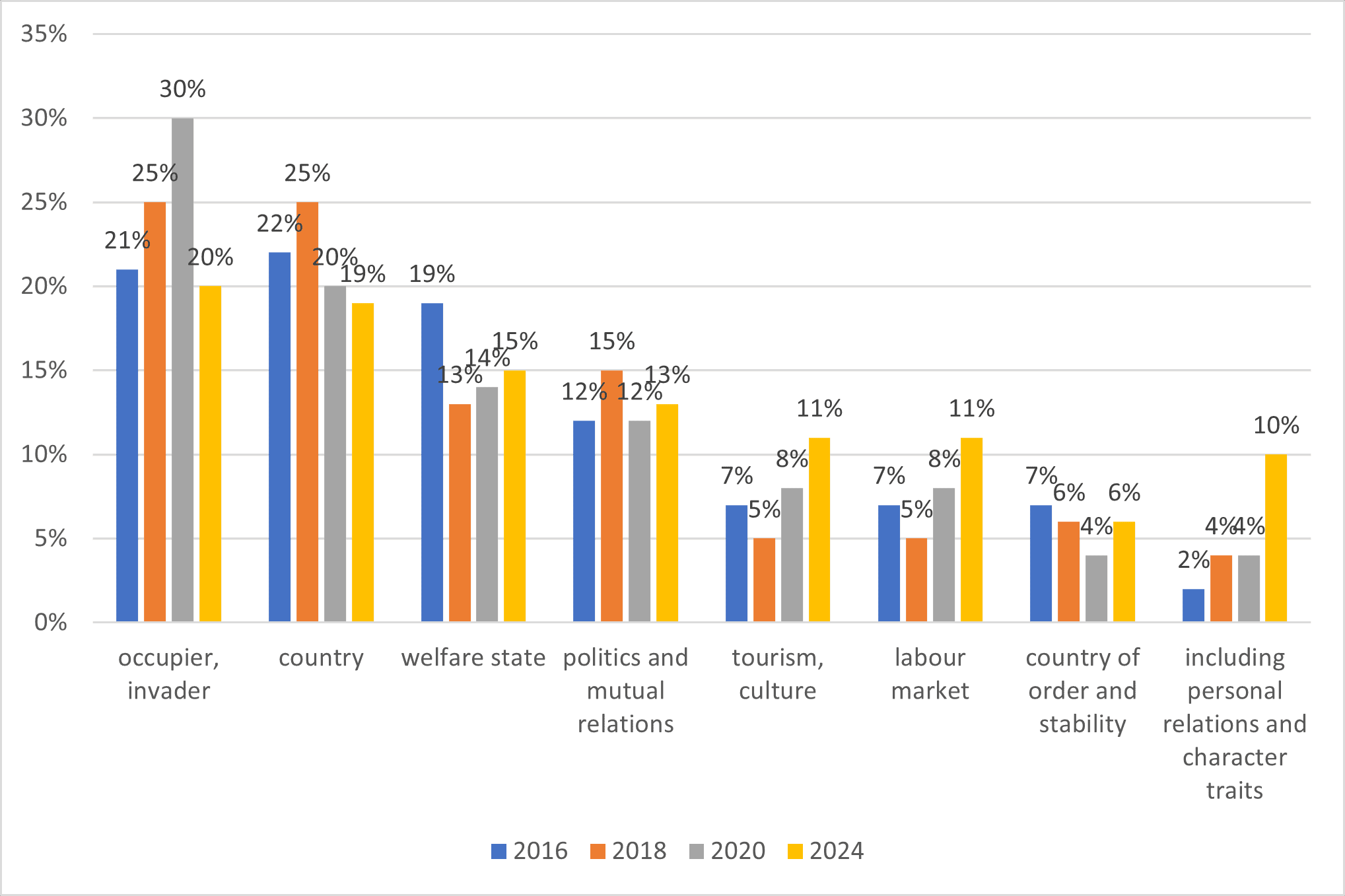

Chart 1. What comes to mind when you hear the word “Germany”? Grouped by category of responses from Poles of 2016, 2018, 2020 and 2024 (in %)

Source: own compilation based on the Poland-Germany Barometer, 2024 (Open-ended question. Respondents could indicate no more than three associations).

Source: own compilation based on the Poland-Germany Barometer, 2024 (Open-ended question. Respondents could indicate no more than three associations).

At the outset, it is worth looking at the data showing the most frequent associations of Poles with Germany. In addition to positive associations, such as “country of prosperity” or “country of law and order,” “occupier, invader” remains a very common association. It is worth noting that the associations of respondents should not be interpreted as unequivocal statements of attitudes. The fact that Germans are associated by some of the respondents with World War II does not automatically mean that these people manifest aversion to German society. What we can infer from the associations of Polish respondents with Germany is that even 80 years after the war, the memory of those events is still alive in Polish society. The frequent occurrence of these associations also confirms the earlier thesis of the article, according to which a difficult history can leave a long-lasting mark on relations between nations.

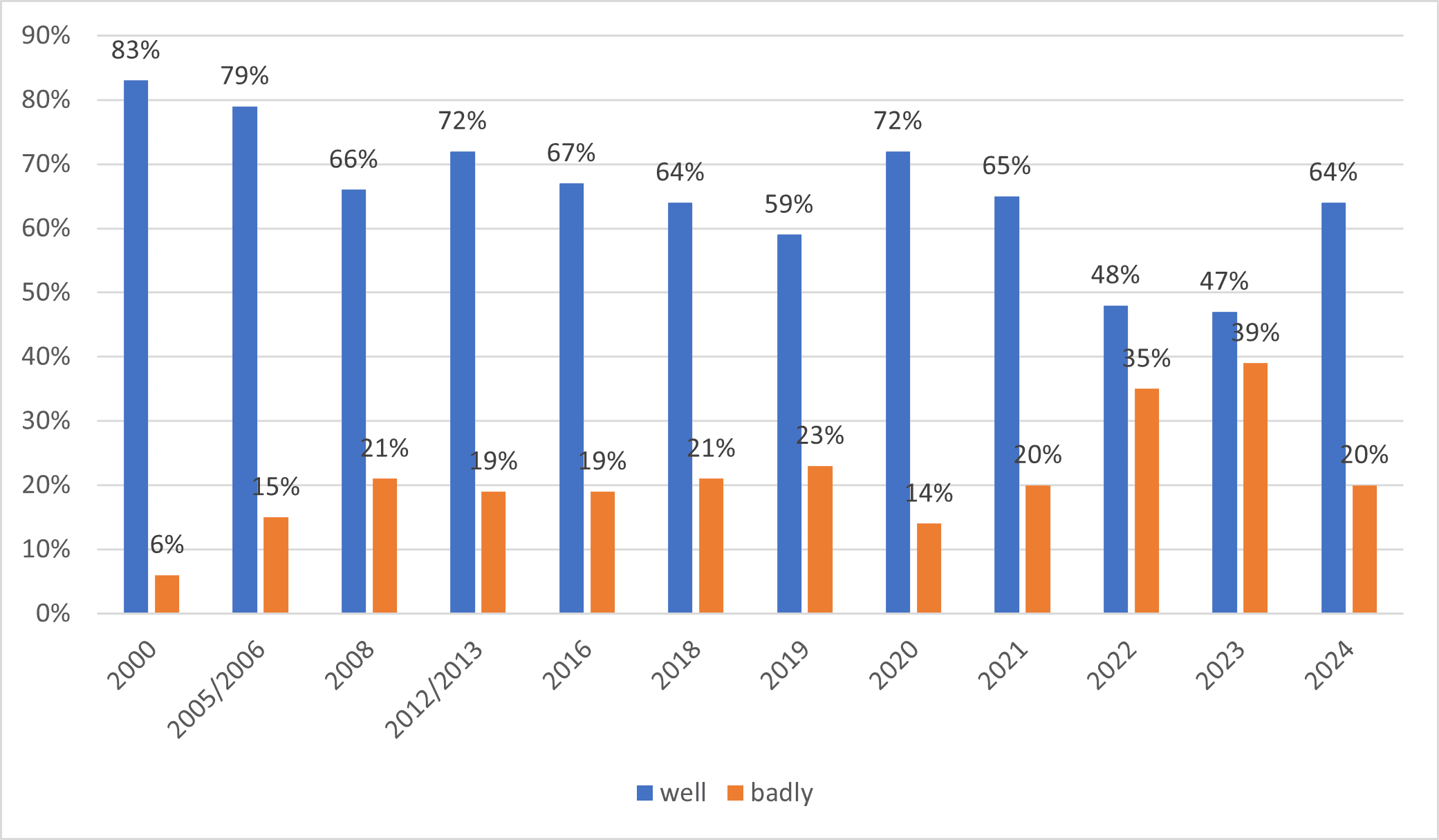

Chart 2. How are relations between Poland and Germany? Responses of Poles expressed in percentages

Source: own compilation based on the Poland-Germany Barometer, 2024.

Source: own compilation based on the Poland-Germany Barometer, 2024.

Chart 2 shows changes in the assessment of Polish-German relations by Polish respondents from 2000 to 2024. For all the years included in the survey, the majority of Poles, despite some fluctuations, described relations with Germany positively. The most recent data from 2024, indicates that as many as 64% of Polish respondents describe relations with Germany positively, compared to 20% of respondents who describe them negatively. In the same survey, the motivations of Poles who described Polish-German relations as “bad” or “good” were also indicated.

Polish respondents who described relations with Germany as “good” or “very good” cited common economic interests (54%), the existence of mutual contacts between Poles and Germans (47%), as well as joint efforts by citizens and organizations of both countries for reconciliation (29%) as the most common reason for their answer.

Respondents who described current Polish-German relations as “bad” or “very bad” cited insufficient settlement of German war criminals and the losses Poland received from Germany during World War 2 as the most common reasons for their answers (60%); the German government’s policies toward Poland (42%) and the divergent economic interests of Poland and Germany (29%).

Analysing the above data, it can be concluded that the assessment of Polish-German relations, both now and in previous years, looks more positive than negative. Nevertheless, this assessment is far from unequivocal, and we can note that part of the Polish public, negatively assesses relations with Germany, pointing, among other things, to the historical past. The combination of this fact with the negative associations of Germany as invaders and occupiers, which are well established in the public consciousness, opens the possibility of instrumental use of these opinions for political purposes.

6. The polish public perception of Germany and its political impact

For many years, Poland has been dominated by two political forces: the Law and Justice Party (PiS) and the Civic Coalition (KO). The first of these- PiS, creates itself as a Eurosceptic and conservative party. The second- KO, for a pro-European and liberal party. After the 2023 parliamentary elections, KO won a majority in the Polish parliament, ending the 8-year (2015-2023) rule of PiS. Although there are other parties in Poland, in this analysis I will focus primarily on the above two. First, because they shape Polish politics to the greatest extent, and secondly, because the actions of PiS in recent years, best reflect how public sentiment toward Germany is exploited in Polish politics.

The division of Poland’s two largest parties into Eurosceptic and pro-European groupings is an important starting point for analysing the electorates of both formations in terms of their perceptions of Germany. This is due to the fact that, as indicated earlier, Germany plays a key role in the structures of the European Union, which means that a sceptical attitude toward the EU can somehow automatically translate into a sceptical attitude toward Germany. In the 2024 CBOS qualitative research communication “20 Years of Poland’s Presence in the European Union,” researchers interviewing residents of the Greater Poland region, noted that “Germany often appears in conversation as a kind of personification of the Union, and at the same time its biggest beneficiary.”[15]

Before giving specific examples of the use of anti-German rhetoric in Polish politics, it is worth looking at the research showing the general attitude of Poles towards Germans, contained in the CBOS research communiqué “Attitude towards other nations one year after the outbreak of war in Ukraine”[16] from 2023. Unlike the results of the research shown in Chart 2, the cited communiqué examined Poles’ attitudes towards Germans, and not towards the policies of the German state. In the survey, 33% of surveyed adult Poles expressed their liking for Germans, indifference 23%, while dislike was expressed by as many as 40%. Comparing the 2023 data with previous years, over the years we can observe much more often sympathy of respondents towards Germans than dislike. The increase in dislike toward Germans in 2023, can be explained by the general trend of increasing negative opinions of Poles toward Poland’s neighbouring countries, resulting from the outbreak of war in Ukraine in February 2022 and an increased sense of fear and uncertainty in society.

Chart 3: Percentage of Polish respondents expressing a positive or negative attitude toward Germans in 2013–2023

Source: Own elaboration based on the CBOS research report “Attitudes toward other nations one year after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine” (2023).

An analysis of the data in Chart 3 covering a 10-year period does not clearly indicate a direct impact of the political situation on Poles’ attitudes toward Germans. In particular, the rule of the Eurosceptic Law and Justice party in 2015-2023 was not associated with an increase in declared aversion to Germany. On the contrary, a gradual decline in the level of aversion in Polish society was observed in 2018-2022.

Increased anti-German rhetoric, present in the message of some political elites during this period, was not clearly reflected in the overall public mood. It is worth noting that although Law and Justice won the 2015 parliamentary elections with 35.70% of the vote, this result did not mean the support of most of the population. Thus, it should be noted that the party represented Poland internationally, but did not necessarily reflect the dominant views of society.

Despite the fluctuations observed in the chart, it is worth noting that between 2013 and 2023, dislike of Germans did not fall below 20%, which means that it is noticeable, even if we cannot speak of a definite and visible dislike in Polish society as a whole.

A more complete picture of Poles’ attitude toward Germans in the political context, will show us the social and demographic determinants of Poles’ aversion to other nations. The CBOSU survey shows that general aversion to other nations is indicated primarily by rural residents and those aged 55-64. Comparing this data with the 2023 CBOS communiqué “Who are the voters of political parties in Poland?” one can see an indirect correlation between the Law and Justice electorate and the profile of the person most often displaying a negative attitude toward other nations – as many as 62% of Law and Justice voters are over 54, and 49% of them live in rural areas.

Differences in attitudes toward Germans between the PiS and KO electorates, can be seen in the Poland-Germany barometer report “Hope and Crisis: Public Opinion on Mutual Relations and Common Challenges” from 2024, which compared the opinions of voters of both parties about Germans.

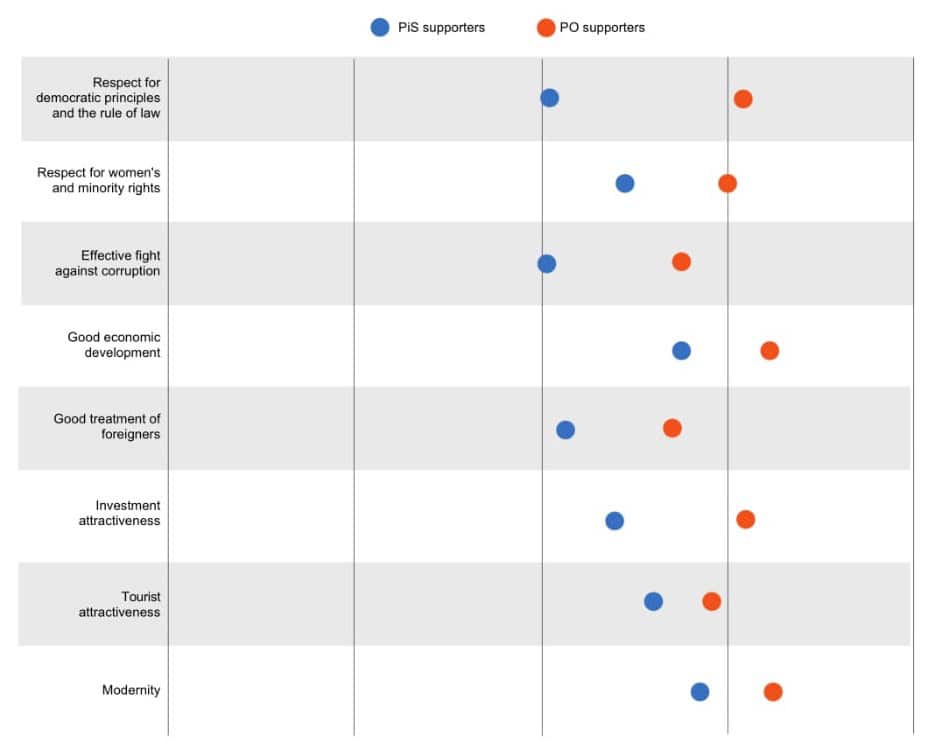

Chart 4: Poland’s image of Germany. Average responses of Poles in 2024, divided into supporters of Law and Justice (PiS) and the Civic Coalition (KO)

Source: Poland-Germany Barometer, 2024 (Respondents gave their answers on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 meant that they strongly disagree with the mentioned statement, and 5 meant that they strongly agree with it).

As we can see in Chart 4, the statistical PiS voter is more sceptical about Germany than the statistical KO voter. This differentiation is in line with the narratives and media messages dominant among supporters of both parties. PiS’s Eurosceptic rhetoric is more likely to emphasize historical pasts and caution toward German politics, while KO’s presents a more open and pro-European stance.

7. Mobilizing the electorate – the issue of war reparations

One example of the use of anti-German rhetoric in Polish politics may be the raising of the issue of Germany paying war reparations to Poland, by the Law and Justice government in 2022. Moving away from a moral assessment of the issue of war reparations, in this part of the analysis I will focus primarily on the goals that the ruling party of the time wanted to achieve by raising the topic of war reparations, which has always aroused a great deal of emotion in Poland.

To put the Law and Justice party’s decisions to come up with war reparations in a broader context, the broader context of those events is necessary. In 2022, Polish-German relations were fraught with tension. The Law and Justice government repeatedly criticized Germany for maintaining close relations with Russia, for presenting a different vision of the European Union’s climate policy, and for interfering in Poland’s internal affairs in the context of disputes over the rule of law.

In this tense atmosphere, full of unrest, we can read the decisions to demand war reparations as part of an internal political strategy aimed at consolidating the electorate around the historical narrative and strengthening the government’s position in international disputes. Raising the issue of war reparations can also be perceived as a desire to politically attack, the then opposition (KO) and portray it as an anti-Polish party, displaying attitudes that serve German interests. The most important person in the opposition at the time and the current Prime Minister of Poland-Donald Tusk, in particular, was portrayed by political opponents as a “German puppet.” The recording of Donald Tusk speaking German and uttering the now famous “für Deutschland” (Eng. “for Germany”) in the Polish public sphere was repeatedly pulled by his political opponents.[17] As was the fact of the (forced) service of Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s grandfather in the Wehrmacht during World War 2.

To confirm the thesis of the mobilization of the electorate around the issue of war reparations, it is worth looking at the opinion polls in the CBOS communiqué “Poles on reparations and Polish-German relations” of 2022.

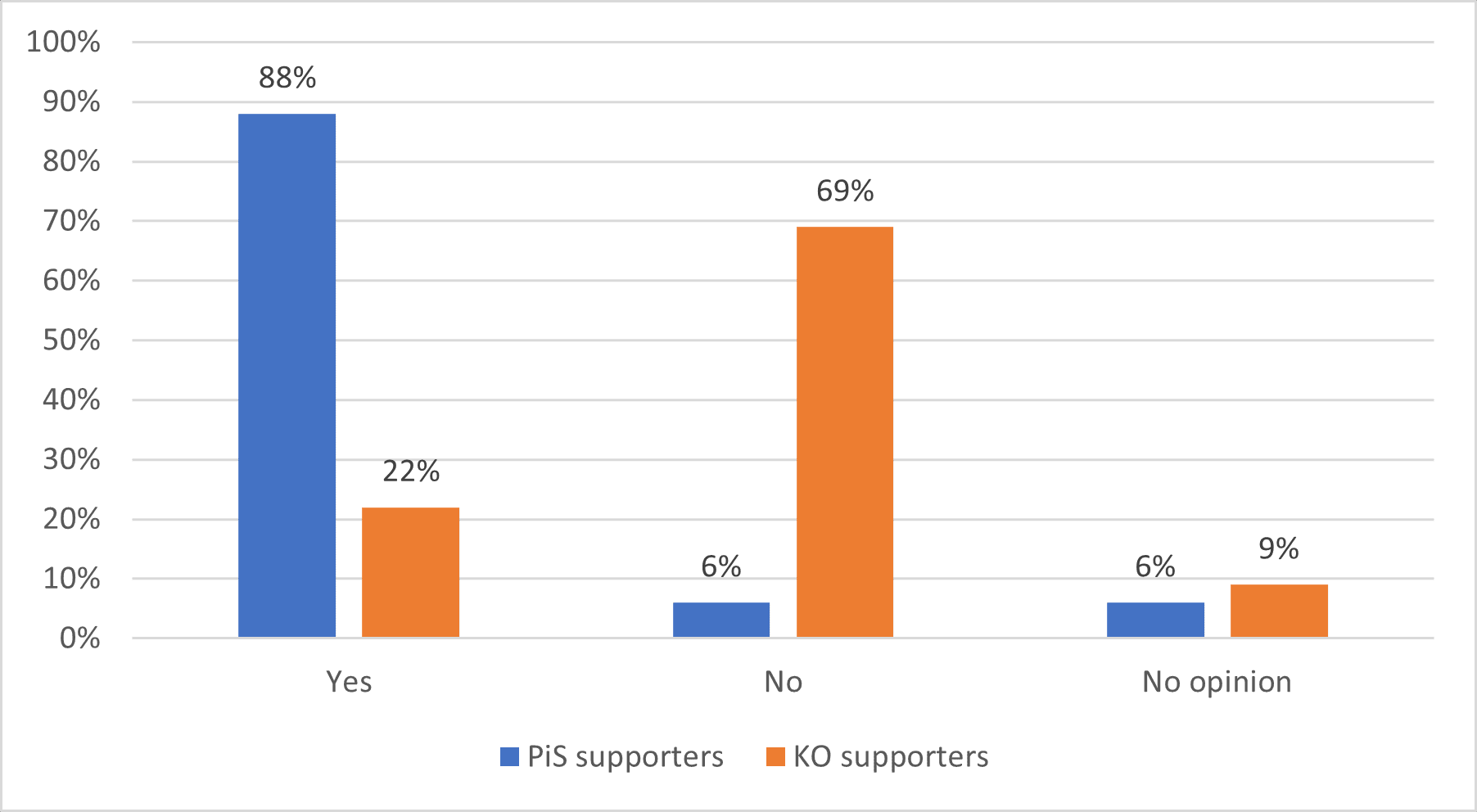

Chart 5. opinions of party electorates on the legitimacy of the demand for war reparations from Germany in 2022

Source: own compilation based on the CBOS report “Poles on reparations and Polish-German relations” in 2022.

Chart 5 shows the opinions of the PiS and KO electorates on the legitimacy of demanding war reparations from Germany. As can be seen, there is a high disproportion, indicating that PiS supporters are much more clearly (88% of respondents) in Favor of reparation demands compared to KO supporters (22% of respondents). The percentage of opponents in the two electorates also differs significantly: only 6% of PiS supporters surveyed oppose reparations, compared to 69% of KO supporters surveyed.

However, the opinions of respondents presented in the survey cannot be interpreted literally, and it should be borne in mind that the survey was created after PiS made reparation claims against Germany. Agreement with the statement that Poland should demand reparations could be interpreted as support for the policies of the current government and its foreign policy.

Nevertheless, based on the data presented, we can conclude that the issue of war reparations raised by the PiS government mobilized a part of the electorate, whose opinion stood in contrast to that of the opposition party’s (KO) supporters.

8. Polish-German action plan

After a period of tension in Polish-German relations, we have recently seen a clear turn toward intensifying bilateral cooperation, possible for two reasons: the first was the outbreak of war in Ukraine and a change in German policy toward the Russian Federation. The growing dependence of the German economy on Russian hydrocarbons, was criticized by the Polish side in previous years and perceived as a short-sighted policy that could threaten the energy security of the entire EU in the future. The joint recognition of the Russian Federation as a threatening state and complicity in the imposition of numerous EU sanctions have contributed to a rapprochement between the Polish and German positions. The second reason for the intensification of bilateral relations between Poland and Germany was the change of government in Poland in 2023 and the winning of elections by the pro-European Civic Coalition, which was more open to cooperation with Germany.

An expression of the warming of Polish-German relations is the “Polish-German Action Plan” of 2024, which contains a series of declarations on Polish-German cooperation in the face of common threats and challenges, covering such spheres as security, energy, education and the rule of law.[18]

An interesting provision in the Polish-German action plan is the one on historical policy, expressed through the commemoration of the victims of World War 2 and the establishment of a German-Polish House with a monument to the victims and a permanent exhibition, as well as support for the history textbook “Europe. Our History” created with the cooperation of Polish and German historians. The fact that the issue of history was raised in the Polish-German action plan testifies to the importance of the influence of history on Polish-German relations. Because of the strong collective memory of the events of World War 2, the topic of Polish-German reconciliation is recurring in the politics of both countries, even in agreements where it is not the main topic. This is because the Polish-German Action Plan was created as a response to both external threats (aggressive policies of the Russian Federation) and internal threats resulting from deteriorating economic conditions and global crises. In conclusion, historical policy, resulting from public expectations, is a topic constantly affecting relations between Poland and Germany.

9. Summary

Polish-German relations from a historical perspective have not been simple. The development of Poland and Germany, both economically and socially, was often influenced by different factors, shaping the national identity of the two countries in different ways. The event that, in the long run, has most strongly oriented Polish-German relations is World War 2, which even today, 80 years after its end, is a topic of debate and a cause of possible disputes. Bearing in mind surveys of Polish public opinion as well as Polish political conditions, one can conclude that the memory of German war crimes, can be a political tool to mobilize the electorate, both in opposition to Germany’s policies and against opposition groups in Poland, which present a more favourable attitude towards the German side.

Although there are disputes between Poland and Germany, there is no doubt that the two countries are interdependent. Poland and Germany have been part of the European Union and NATO for many years, which means that their interdependence is based on both trade relations and security issues. The need to tighten cooperation is particularly evident today and is best exemplified by the Polish-German Action Plan, which demonstrates the desire to strengthen alliance relations, in the face of common interests and geopolitical tensions.

10. References and endnotes

- Marshall, Tim. Więźniowie geografii, czyli wszystko, co chciałbyś wiedzieć o globalnej polityce. Poznań: Zysk i S-ka Wydawnictwo, 2017. ↑

- European Union. “Deklaracja Schumana – maj 1950 r.” Ostatnio zmodyfikowano 9 maja 2020. https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/history-eu/1945-59/schuman-declaration-may-1950_pl. ↑

- More precisely: the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. The use of the term “Germany” in this context is a deliberate simplification, intended to improve the clarity and readability of the text. ↑

- The concentration of wealth and urbanization in Western Europe remains clearly visible today, for example in the visualization of the so-called “Blue Banana” – a region stretching from southern England, through northeastern France, Belgium, the Netherlands, western Germany, and Switzerland, all the way to northern Italy. ↑

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011. ↑

- The concept of the nation-state emerged in the 19th century as a response to the ideals of the French Revolution, which held that power in a state should belong to the people, rather than, as had previously been the case, to a monarch. At that time, the term “nation” began to denote a community of people united by a common language, culture, traditions, and shared history. The idea of the nation-state inspired many unification movements, most notably in Germany and Italy, which ultimately led to the creation of unified state structures. In the 19th century, Poles lived under the rule of three partitioning powers. The idea of the nation-state, understood as a sovereign state of their own, played a crucial role in preserving Polish national identity and was one of the key factors that made it possible for Poland to regain its independence in 1918. ↑

- Zieliński, Robert, Małgorzata Gruchoła, Ziemowit Socha, Dariusz Tułowiecki, i Monika Popielewicz-Durakiewicz, red. Jak stajemy się Polakami? Edukacja szkolna ku tożsamości narodowej. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, 2024. ↑

- Leszkowicz, Tomasz. “‘Wychowanie Na Tradycjach’ Jako Element Pracy Politycznej w Ludowym Wojsku Polskim w Latach Sześćdziesiątych i Siedemdziesiątych XX Wieku.” “Polska 1944-1945-1989. Studia i Materiały” XIII (2015): 101–28. ↑

- Tomasz Skonieczny and Fundacja “Krzyżowa” Dla Porozumienia Europejskiego, (Nie)Symboliczne Pojednanie: rozważania o relacjach polsko-niemieckich po 1945 roku, 2019. ↑

- ibiden ↑

- Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). Rangfolge der Handelspartner im Außenhandel der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (vorläufige Ergebnisse) 2024. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt, 20. März 2025. https://www.destatis.de. ↑

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Obroty towarowe handlu zagranicznego ogółem i według krajów w styczniu–grudniu 2024 r. Warszawa: GUS, 14 lutego 2025. https://stat.gov.pl. ↑

- Deutsche Bundesbank. Direktinvestitionsstatistiken. Aktualisierte Ausgabe. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Bundesbank, 30. April 2024. https://www.bundesbank.de/Navigation/DE/Statistiken/Zeitreihen_Datenbanken/Makrooekonomische_Zeitreihen/its_details_value_node.html?tsId=BBFBOPV.A.N.DE.W1.S1.S1.T.A.FA.D.F._Z.EUR._T._X.N.ALL. ↑

- Ministerstwo Rozwoju i Technologii, Polsko-niemieckie konsultacje międzyrządowe – wymiar gospodarczy, Gov.pl, dostęp 10 kwietnia 2025, https://www.gov.pl/web/rozwoj-technologia/polsko-niemieckie-konsultacje-miedzyrzadowe–wymiar-gospodarczy. ↑

- Fundacja Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. 20 lat obecności Polski w Unii Europejskiej: Komunikat z badań jakościowych. Nr 4/2024, ISSN 2956-7394. Warszawa: CBOS, kwiecień 2024. ↑

- Fundacja Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Stosunek do innych narodów rok po wybuchu wojny na Ukrainie: Komunikat z badań. Nr 33/2023, ISSN 2353-5822. Warszawa: CBOS, marzec 2023. ↑

- Bankier.pl. „Telewizja publiczna przeprosiła Donalda Tuska. Chodzi o słynne ‘für Deutschland’.” Ostatnia modyfikacja 30 lipca 2024. https://www.bankier.pl/wiadomosc/Telewizja-publiczna-przeprosila-Donalda-Tuska-Chodzi-o-slynne-fur-Deutschland-8790000.html. ↑

- Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej i Rząd Republiki Federalnej Niemiec. Polsko-Niemiecki Plan Działania. Warszawa, 2 lipca 2024. ↑