by Piotr Nowak, University of Warsaw

Introduction

Since its inception in 2012, China’s “17 + 1” cooperation platform — an initiative aimed at deepening Beijing’s economic and cultural ties with 17 countries in Central and Eastern Europe — has sparked considerable speculation about China’s motivations and raised concerns about the format’s tangible deliverables. Beijing’s initiatives to finance essential infrastructure, promote foreign direct investment (FDI), and expand trade have generated controversy both inside the 16 participating nations and among EU neighbours. However, despite this climate of political ambiguity, the Baltic nations have been able to capitalise on their connection with China without antagonising Brussels, up until this year.

China has made significant gains in the last decade toward integrating Eastern Europe into a web of cooperative partnerships. In what can be defined as the swiftest international policy in the last century, Beijing promised significant financial investments in the region via a chequebook diplomacy strategy. Following the introduction of the so-called 17 + 1 platform (initially 16 + 1, up until Greece joining), Eastern Europe’s relations with the developing superpower grew stronger and looked to be relatively frictionless. China’s courtship of this region of Europe alarmed Brussels governance, who feared that the Chinese Communist Party may use its financial and technological strength to create a schism between EU member states. However, as time has passed, three of the forum’s member countries — Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — have noticeably ceased rowing in Beijing’s direction.

A Part of a Greater Strategy

As the Communist Party of China’s 19th National Congress closed in October 2017, observers declared Xi Jinping’s “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” the conference’s crowning achievement and “Chinese Diplomacy for a New Era” the conference’s most significant innovation. While the notion has only lately achieved such prominence, it has been practised for nearly five years, showing the Chinese nation commitment to their strategy. The Baltic republics, in particular, have served as a litmus test for China’s new diplomatic strategy.

China’s new foreign policy concept was entrenched in the Party constitution as “a community with a shared future for humanity’. When China first expressed its desire to unite a diverse group of Balkan, Baltic, and Central European countries in the document “China’s Twelve Measures for Promoting Friendly Cooperation with Central and Eastern European Countries,” many commentators noted that the 16 newly proclaimed partners shared nothing more than their socialist pasts and a desire to avoid antagonising Russia: for instance, both Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine, and Kosovo were ostensibly omitted from the invitation for Russia-related concerns.

As collaboration progressed, a number of issues arose, the most obvious of which were political objections from Western European politicians who said China was attempting to divide the EU. Yet, the “divide and rule” allegation levelled at China’s actions was not a point of contention among the Baltic states, not at the Bruxelles level. The pro-EU Baltic states have refrained, when the discussion started, from using China as a bargaining chip in intra-European negotiations, noting that the “17 + 1” cooperation platform complements the EU-China Strategic Partnership conversation.

In 2019, the New York Times ran a major exposé of internal Chinese government documents that have been leaked. According to the materials, China’s president is actually quite knowledgeable and well versed in the Baltic countries’ history. He allegedly warned in one of his addresses that, while economic development is a ‘primary objective and the foundation for attaining permanent stability,’ it is erroneous to believe that ‘with progress, every problem resolves itself.’ .

The Baltic States and “17 + 1”

While Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia were caught away by the format’s size, they embraced this new avenue for cooperation. Officials wanted to minimise their trade deficits with China, attract Chinese direct investment, and integrate their transportation infrastructure into the network of roads, railroads, and ports that connect China to Europe. Due to the Baltics traditionally limited economic relations to China, the bar for success was relatively low. This set the Baltic nations apart from other “16 + 1” (today 17 + 1) members such as Hungary [editor note: for which Blue Europe will publish a full report soon about the links between China and Hungary], the Czech Republic, Poland, Serbia, and, to a lesser extent, Slovakia, which already had a strong reputation in China and a history of collaboration. Hungary, for example, dominated the region in 2013 in terms of attracting Chinese capital investment, increasing the standard for the newly established cooperation platform. Due to the Baltic states’ initial lack of ties to China, any improvement in relations was welcomed.

The disconnect between expectations and reality is the most serious challenge confronting China’s “17 + 1” collaboration policy, with a special emphasis on the Visegrad Group countries of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. Disappointment may stem from the fact that the anticipated investment flow did not materialise. The critical “17 + 1” role ascribed to these countries by official Chinese rhetoric heightened expectations.

The Baltic States have never had exaggerated expectations. As Estonia’s Ambassador to Latvia, Tonis Nirk, described it, “the sixteen nations that participated in the Format were essentially concerned in two things: access to the Chinese market and logistics and transportation cooperation.” As a result, when Lithuania and Latvia joined the format in 2012, the greatest danger they foresaw was going unnoticed by the various other countries interested in engaging with China. All of the “17 + 1” countries made identical sales pitches, claiming to be “gateways to the East” and “perfect locations for China to enter Western European markets.”

Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia also recognized that their shared characteristics acted as roadblocks to cooperation with China: their geographical location, the small size of their domestic markets (the total population of Baltics countries is similar to either Slovakia or Hungary), and their lack of brand recognition in China. Another roadblock in the construction of infrastructure was a lack of EU funding and the incompatibility of Chinese agreements with EU laws, especially in matter of competition and common markets. With such low expectations, each positive development — whether in logistics, trade, or interpersonal interactions — had the potential to become a success story. As a result, the Baltic states did not share, at least to start, their Central European colleagues’ dissatisfaction with China’s glacial pace of cooperation — because their initial expectations were acceptable.

On the contrary, in the first years, Latvia was even qualified by a paper as a “ambitious partner” of China. Sino-Baltic cooperation was even pushed through non-Chinese channels, such as the Nordic Baltic Eight (NB8), a group of eight Nordic and Baltic countries that sent a parliamentary delegation to Beijing in January 2018. Even if the economic content of China’s new involvement remains limited, the diplomatic symbolism was sufficient to sustain both China and the Baltic states’ interest in the relationship.

After almost ten years of collaboration under the “17 + 1” structure, none of the sixteen partners demonstrated a significant rise in Chinese investment in their economy. However, the Baltic states have achieved a number of objectives. They have maintained cordial connections with China while adhering to the EU’s official position, for example, when expressing concern about EU companies’ limited access to Chinese markets or during disputes over EU human rights pronouncements in China. Notably, Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania have advocated for the inclusion of European institutions and adherence to EU values during “16 + 1” debates, most recently at the 2016 Riga Summit. hey also channelled China’s political desire for cooperation into increasing their visibility in a rising great power. Given their low expectations about relations with China, this represents a real success for Baltic diplomacy.

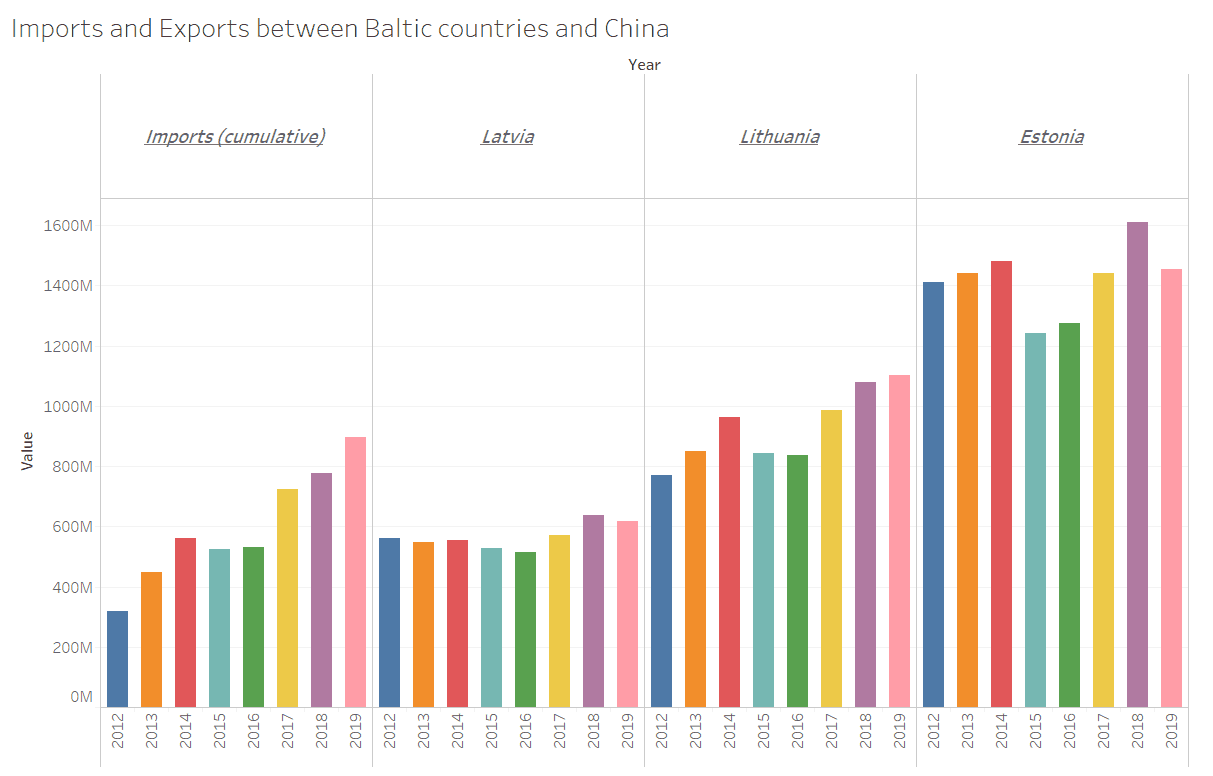

On the economic front, the commercial balance has kept degrading between China and the Baltics. This graph, made from data from the OCE, shows how the total imports from the Baltics to China (first column), is similar only to those exports from Latvia to China. Far from correcting, the commercial balance has kept getting worse for the Baltics countries in general.

Yet, the exports (numbers from 2019) to China from the Baltics are extremely limited, especially compared to nearby and small countries. Italy, who is almost on the other side of Europe, has a larger share of exports from the Baltics than China itself.

Not everything was bad, though. Cooperation in high-tech has been a priority for the Sino-Baltic relationship since China’s engagement with the region began in the early 2010s. The Baltic states believed they did not require Chinese loans and instead could establish high-value-added cooperation in cutting-edge sectors that benefited from the complementarity between China’s technological development and the Baltics’ highly educated workforce, low production costs, and digital orientation. This framework was backed, at least symbolically, by all three Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian states.

Building on Estonia’s reputation for e-savviness, China and Estonia signed a Memorandum of Understanding on the Digital Silk Road in 2017. The document promised, “the development of e-commerce ecosystems, digital services, the exchange of technical information as well as facilitating the connectivity of logistics and trade information.” While not directly tied to the political process of Sino-Baltic contacts, a concrete illustration of technological cooperation occurred earlier that year in the form of China’s Didi Chuxing became a strategic partner to Taxify (now known as Bolt), an Estonian-founded ride-sharing company.

Lithuania, meantime, was chosen to host the secretariat for Fintech cooperation under the “16 + 1” (later renamed “17 + 1”) arrangement between China and Central and Eastern European governments. In 2018, Vilius apoka, the finance minister at the time, called the decision “a perfect example that China and Central and Eastern European countries are linked by common interests, i.e., creation of attractive environment for financial innovations and promotion of development of innovative business.”

Although Latvia aimed lower and prioritised logistical collaboration over high-tech cooperation through “16+1,” the notion of cooperation in technology persisted. Following a EUR 15 million investment from BGI Group, a biotech genome sequencing giant out of Shenzhen, a gene-sequencing equipment production facility was opened in the country.

Although scattered across different technology fields and different in size, these examples nevertheless demonstrate a joint initial determination by the Baltics to take advantage of China’s technology.

Baltic states slowly starting to turn away from China: from Nuctech to the forbidden list

By 2018, however, this had changed as the broader discourse around China shifted from being a national issue to a keystone of the transatlantic alliance. Why exactly did this once seemingly promising economic partnership sour so quickly?

The Chinese side may have underestimated the significance that the region’s primary geopolitical competitor, the United States, plays. It’s difficult to overstate Washington’s strategic influence on NATO’s eastern flank. For the last two decades, the Baltic states’ foreign policy credo has been to align themselves as closely as possible with the alliance’s hegemon.

As a result, it was no coincidence that Estonia was one of the first EU member states to sign a declaration with the US government essentially blocking Huawei from operating in their territory. Latvia and Lithuania immediately followed. When Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania signed Joint Declarations and MoUs on 5G security with the United States in 2019 and 2020, pledging to take “into account risk profile assessments” and to conduct “careful and complete evaluation of component and software providers“, the message was clear. The Baltics, along with several other European Transatlanticist states, had made a decision to move away from strategic ambiguity surrounding Huawei and into a clear-cut geopolitical position – namely, US-led security first, EU aspirations for strategic autonomy second.

The Baltic states growing suspicion of the People’s Republic of China’s by the Baltics administration and governments may be monitored in 2020 through the countries’ annual national intelligence reports. Historically, these strategic texts have been almost entirely focused on Russia, their larger eastern neighbour. Paragraphs and pages were reserved for the threat posed by China. the Global Times, the CCP daily newspaper, described as an attempt to “reinforce ‘The China Threat.’

This year, in January, Lithuania’s government banned China’s state-owned company Nuctech from supplying X-ray scanning equipment to local airports in January, citing national security concerns. The decision, which was criticized by the Chinese embassy in Vilnius, grabbed the attention of Global Times. In this article, a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences said that “by playing hardball with China, its primary purpose is to give in to the US”.

NucTech had previously received contracts in Latvia (the equipment was allegedly purchased for the use at Latvian customs, not airports) and Lithuania, among a long list of other European countries from 2007/08. It was the most reasonably priced product on offer. NucTech’s pricing strategy has consistently been under market rates – so much so, that the EU accused the company of dumping in 2010. The issue was resolved by creating industrial facilities in Warsaw, Poland, adjacent to the Baltic countries. Prices climbed slightly but remained competitive, assisting in the proliferation of NucTech equipment throughout Europe. As a result, the company that won the Lithuanian offer was not exceptional.

Ultimately, however, the Lithuanian government cancelled the contract. The government explained the decision as a matter of national security: “The government’s decision is that the deal is not in line with national security interests,” Rasa Jakilaitienė, the prime minister’s spokeswoman commented on the matter.

The Lithuanian decision had come directly after the US had added NucTech to the List of entities that “have been involved, are involved, or pose a significant risk of being or becoming involved in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States” in late 2020. The blacklisting was followed, according to the Wall Street Journal, by the “campaign led by the [US] National Security Council and a handful of US agencies … trying to rally European governments to uproot NucTech Co.” Recognising the strategic nature of its partnership with the United States, the Lithuanian government chose to veto the contract. And Lithuania is by no means an exception in this sense among the Baltics. According to sources, both Riga and Tallinn would make the same choice if presented with a comparable problem.

On February 9, the Baltics appeared on China’s radar again. The 17 + 1 summit, presided by China President, Xi Jinping himself, was partially ignored by Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and several other countries that sent ministers instead of heads of state. In February, Lithuania’s Parliamentary Committee on Foreign Affairs agreed that the country should leave the 17 + 1 format altogether, with Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis later saying that it has brought “almost no benefits” and is used to “divide Europe”.

Chinese leadership were hoping to receive the presidents and prime ministers in Beijing, but due to the pandemic the meeting took place in front of computer screens. The gesture by the Baltic states did not pass without notice in China.

On the night before the summit, the Chinese Foreign Ministry summoned the Lithuanian and Estonian ambassadors to explain their leaders’ decision, according to Edward Lucas from the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) in Washington.

“From the Chinese perspective, this is very serious,” said Konstantinas Andrijauskas, an expert on China at Vilnius University’s Institute of International Relations and Political Science (TSPMI). “At least some officials in Xi Jinping’s environment, say, the [Chinese] Foreign Ministry, may treat this as an insult. Xi Jinping is not used to such behaviour – if he invites someone, everyone must be present,”

What future for China in the Baltics — Cybersecurity, does it really matter?

In September 2020, a leak from a Chinese company, Zhenhua Data Information Technology, which is linked to the Chinese government and armed forces, showed that it was collecting data on some 2.4 million people around the world – all of them related to the 17 + 1 format, including over 500 people from Lithuania. This September, another “IT scandal” rose. While China’s rigorous control over what its citizens are permitted to read and write on their cellphones has never been a secret, Lithuanian authorities, on the other hand, were caught aback when they discovered that a popular Chinese-made smartphone sold in the Baltic nation hid a dormant feature: a censorship list of 449 terms outlawed by the Chinese Communist Party. Lithuania’s government promptly pushed officials who were using the phones to discard them.

From China’s perspective, last september publishing of a study on Chinese-made cellphones by Lithuania’s Defense Ministry Cyber Security Center was yet another provocation. The center uncovered a concealed registry that permits the detection and censorship of phrases like as “student movement,” “Taiwan independence,” and “dictatorship.”

Beijing is outraged, recalling its ambassador, stopping Chinese cargo rail service into the country, and effectively prohibiting numerous Lithuanian exporters from selling their products in China. Chinese state media have mocked Lithuania, accusing it of becoming Europe’s “anti-China vanguard.”

According to Margiris Abukevicius, a Lithuanian deputy defence minister in charge of cybersecurity, the registry is “shocking and quite terrifying.” Apart from recommending government agencies to destroy the phones, Mr. Abukevicius added in an interview that ordinary users should assess their “personal tolerance for danger.”

Closely aligned with the US in strategic affairs, the Baltic states are frequently eager to accommodate the US’ geopolitical goals. This complicates China’s efforts to establish a foothold in the region.

“The recent 17 + 1 summit was disappointing for China. […] The investment that China promised has largely failed to materialise,” said Chris Miller, director of the Eurasia Programme at the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI).

“The expectations that political and economic leaders in Central Europe and the Baltics may have had, have been frustrated,” said Konstantinas Andrijauskas, Associate Professor of Asian Studies and International Politics at the VU IIRPS. “There are no indications that Beijing will return its focus to the region or showers us with mountains of gold and rivers of honey and milk. […] It’s important to answer whether there are still any benefits from participating in the format that raises concerns for our partners and allies,”.

China will not turn away from the region. “The fact that China already imagines itself as a superpower means that Beijing is interested in all regions and countries of the world,” said Andrijauskas. “When we acknowledge this fact, it will be easier to understand China’s actions,”

The Chinese leadership has demonstrated a tendency in alienating prospective partner governments. It has reacted angrily to any criticism of its human rights record. Local Chinese embassy websites in the Baltics frequently sound like a manifesto for a misunderstood superpower, replete with propagandistic declarations pleading with Baltic governments to abandon their Cold War worldview. To illustrate, in response to an Estonian intelligence assessment, the Chinese embassy in Tallinn declared: ‘The Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service is requested, based on facts and truth, to correct its wrong expressions.’

In a similar vein, following a debate in Lithuania’s parliament over China’s human rights violations, Chinese MPs sprung into action by denouncing the debate as ‘an anti-China farce choreographed by some anti-China individuals intended to smear China’. Whereas Baltic officials initially looked to be prepared to compartmentalise their differences on human rights problems for economic gain, they now clearly do not want to simply gallop along, for various reasons. Last summer, China’s Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying stated that Washington is “assembling its henchmen to blackmail, assault, and oppress Chinese firms.”

There is no “option” for Central and Eastern European countries between the American and China — all NATO members in the region chose to rely on the United States. “The US continues to encourage European partners not to ‘free ride’ on the alliance by relying on the US to stand up to China politically while seeking economic gains from Beijing. The Biden administration is almost certain to maintain the approach. For instance, in the previously quoted Huawei affairs, Estonian Minister of Foreign Affairs put it at the time: “It is important to make sure that the development of European defence cooperation complements the European security architecture based on transatlantic ties instead of attempting to replace it.” A very sound support of their American ally.

Yet the Baltics face a big problem about their “vision” of the EU and NATO: Atlanticism and Russophobia is in sharp decline, especially after the Australian submarine’s affairs. The French president Emmanuel Macron, keeps calling for more dialogue with Russia, a country considered the number one security threat to most Baltic countries. As a more hawkish line on China was one of the core American requests, which no Western country is ready to follow.

Apart from minor policy differences, all three Baltic countries have exhibited a broadly similar view of China’s position in the region. They are eager to pursue high-value-added commercial prospects while avoiding ceding political influence to China. They make no attempt to leverage Beijing against Brussels and, most crucially, they remain steadfast in their transatlantic pledges. The technological factor is particularly relevant because it was intended to be a focal point of the Baltic republics’ relations with China.

As tensions between the US and China are expected to persist and the dilemmas surrounding cooperation with China in technology continue to pervade international security discourse, the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia are increasingly opting out of collaboration with China in technology. They are making a deliberate choice between a transatlantic alliance and EU aspirations for strategic autonomy or the more permissive agenda promoted by large European economies. Washington is the most important security partner for Vilnius, Riga, and Tallinn.

“The small European country will be hoisted by its own petard by acting as a ‘chess piece’ in the US’ strategy against China,” Wang Yiwei, director of the institute of international affairs at Renmin University

“[they] miscalculated China’s economic influence by overestimating itself in a desperate bid to gain more benefits. Lithuania is sacrificing its national interests by cooperating with the unreliable US”.