The Western Balkans have long served as a geopolitical ‘chessboard’ between Russia and the West. The region’s protracted EU accession process and current enlargement fatigue provide Russia with a rare opportunity to further expand its influence in the region, ultimately weakening the functions of the EU and NATO. While Russian economic efforts cannot compete with EU investment and funding in the region, its deep and historical cultural proximity with Serbia still bonds the two nations together.[1]

Serbia-Russia relations during the centuries

It is a rather complicated set of interests that has bound Russia to the core of the region dominated by the Balkans for millennia. It is a relationship that has remained tense throughout its history, despite the fact that the two territories have been at the centre of some of the most radical and dramatic political, economic and border developments that the contemporary world of international relations has ever seen. The Treaty of Kucuk Kaynarca (1774), which dealt the blow that marked the slow and inexorable decline of the Ottoman Empire, granted the Tsarist Empire not only the outlet to the Black Sea and the right of transit through the Dardanelles, but also the right to oversee the protection of the numerous Orthodox prelates. Eager to pursue the expansion plan that would bring Russia to complete dominance over the straits of the warm seas, the tsarist leadership saw the Serbian element and its goals of identity realisation as a potential picklock that could shatter the Ottoman hegemony over south-central Europe.

What followed was a century of revolts and the gradual recognition of Belgrade’s autonomy by the Sublime Porte. Yet despite shared political goals and a brotherhood cemented by language, family and religion, Russia and Serbia maintained a shifting, ambiguous and at times extremely uncomfortable relationship. During the Crimean War, from 1806 to 1812, Belgrade supported St Petersburg in its fight against the Turks, although it advocated the policy of neutrality first adopted by Austria (1853-1856). On the other hand, at the decisive moment, the Tsarist Empire supported the uprising that led Serbia and Montenegro to declare war on the Sublime Porte in 1876. However, after the two Balkan nations suffered their first military defeats, the Tsarist Empire withdrew its support and turned its attention to Bulgaria. Therefore, the full international independence granted to Serbia, led by the Obrenovic dynasty, at the Congress of Berlin in 1878 was realised with the blessing of Austria-Hungary, which also interceded to ensure that Serbia received the lands that St. Petersburg had intended for Bulgaria. In June 1903, a terrible massacre removed the pro-Russian Karadjordjevics from the Serbian throne and reinstated the pro-Obrenovich Obrenovic family. Obviously, the most permanent evidence of the newly formed coalition was the First World War. It led, among other things, to two major transformations: the emergence of the Soviet Union, on the one hand, and a unified kingdom with Serbs, Croats and Slovenes under the same sceptre, which, after the (ninth) coup d’état in 1929, adopted the name of Yugoslavia.

The events that led from the Second World War to the beginning of the Cold War in Europe included a disruption of the usual geostrategic trends. In his meetings with Milovan Djilas, Tito’s right-hand man and a key intellectual in the emerging Communist Yugoslavia, Stalin summed up the situation. In a collection of memoirs, Djilas describes how the Georgian commander defined the impact of the struggle as the beginning of a new era, stressing that for the first time in history, people who conquer a country impose not only their military presence but also their socio-economic system. In Yugoslavia, the ideology of the federation led by Tito remains to some extent subordinate to traditional geopolitics, which, mutatis mutandis, echoes that of nineteenth-century Serbia, which was liberated mainly by exploiting the rivalries between the Tsarist and Austro-Hungarian empires.

Since the famous break with Stalin in 1948, Belgrade has survived in the bipolar tension by getting caught up in the competition between the Soviet Union and the United States: Tito remained an orthodox Communist until his death, but if in 1956 he supported Moscow’s intervention in Hungary, in 1968 he condemned it as aimed at crushing the Prague Spring, or in the last months of his life, at the 1979 summit in Cuba, he fought with all his might to prevent his Non-Aligned Movement from being The dramatic consequences of the end of the bipolar world affected Moscow and Belgrade in particular: From their respective disintegration emerged a Russian Federation, almost painlessly, and a newly independent Serbia, bloodily defeated in its efforts to maintain a unified state and not yet fully reconciled with some of its new neighbours in the region.

If in the 1990s Yeltsin’s Russia, despite providing Belgrade with limited economic support and acting as a megaphone for Serbian demands in the United Nations Security Council, failed to impose itself diplomatically on the United States and NATO, on the other hand the rise of Vladimir Putin has restored Moscow to its prominent position in the Western Balkans.[2]

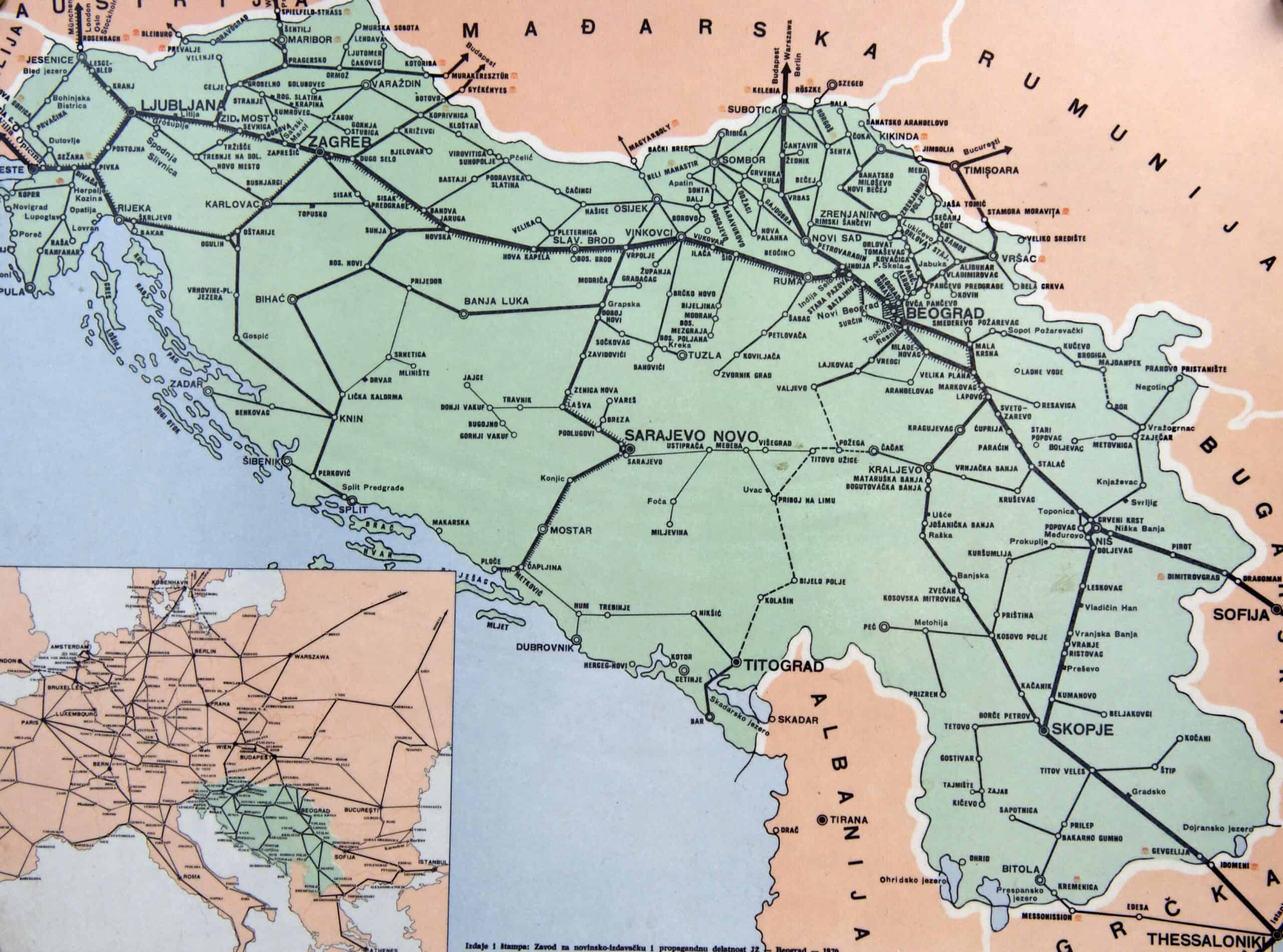

After the expansion of the Atlantic Alliance in 2004 reduced Russia’s sphere of influence to the West, Russia responded by focusing its efforts on relations with its traditional Orthodox brethren, expanding their diplomatic[3], commercial[4] and military[5] ties. In terms of economic relations, Moscow has primarily invested in the energy and infrastructure sectors, thanks to a 2008 agreement in which Gazprom acquired more than 50 per cent of NIS[6], Belgrade’s counterpart, and more recently with a 2015 agreement, finalised last summer, to invest more than $800 million in the modernisation of Serbia’s railway network[7], after Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic declined Brussels’ invitation to join the European Union’s economic sanctions in 2014[8]. On the military side, for instance, in 2012 Russia built a facility in southern Serbia, near Ni airport, which was officially used as an emergency centre for natural disasters but was seen by Western analysts as a response to NATO’s expansion policy in Montenegro and equipped with capabilities far beyond humanitarian purposes[9]. Moscow also supplied Belgrade with several MiG-29 fighter jetsover the time[10].

The current President of the Republic received support from Vladimir Putin, yet, widening the political-international lens, it cannot be ignored that, even in the current scenario, Belgrade cannot avoid counterbalancing the Russian shadow by looking to the West: like Vienna in the nineteenth century or Washington in the twentieth, the friendship of Brussels is today a necessary reference for the survival of the Orthodox Republic as well as the periphery. Putin has expressed the expectation that Vucic’s successor as prime minister will also prioritise the Moscow-Belgrade fast track, and there is little doubt that the new government, regardless of its leader, will not cut ties with Russia.

Equally clear, however, is that he will remain steadfastly committed to the path he has been preparing for the past decade: that of Serbia’s final integration into the European Union. The country has shown a willingness to move closer to Europe in recent years and has begun the process of EU integration. The accession process officially began in 2008, when the country signed the Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) with the EU[11], but talks on the SAA began in 2005, when Serbia was still a confederation with Montenegro. In 2009, the country submitted its application, and in 2012 the European Council granted it formal candidate status. From 2013 to 2014, screening and talks began, covering as many as 24 chapters.

“Recent” estrangement with Kosovo and the EU

In contrast to the process of integration, it’s relevant to note that Serbia is the only country in the Western Balkans that has not imposed sanctions on Russia, despite intense pressure from the European and American sides to do so in retaliation for Russia’s actions against Ukraine. President Vucic refused[12], arguing that such measures were not in the country’s interests. This led to a breakdown in the negotiation process, especially in the cluster on the EU’s foreign and security policy, which requires strict compliance with European decisions for this chapter to succeed. In fact, in 2022, all European institutions urged Serbia to adopt the same sanctions as the EU[13]. In the Balkans, unlike Serbia, the other non-EU states, such as Montenegro and North Macedonia, have adopted sanctions against Russia in line with the EU.

Kosovo’s interior minister, Khilal Svekla, recently accused Serbia of trying to destabilise his country under Russian influence by supporting the Serb minority in northern Kosovo, which has blocked highways in an escalation of weeks of demonstrations[14].

Serbs in the ethnically divided town of Mitrovica in northern Kosovo erected additional barriers on Tuesday, hours after Serbia announced it had put its armed forces on maximum alert following weeks of heightened tensions between Belgrade and Pristina over the protests. This is the first time since the start of the latest crisis that Serbs have used loaded trucks to block motorways in one of Kosovo’s main cities.

Almost 50,000 Serbs live in northern Kosovo and refuse to recognise the Pristina administration or Kosovo as an independent state[15]. They regard Belgrade as their capital and want to keep their Serbian number plates. Serbia denies wanting to destabilise neighbouring Kosovo and claims it is merely defending the unrecognised Serb minority living in what is now Kosovo.

As a result, Serbia is increasingly caught between two competing realities. It is trying to juggle as best it can. It is the non-EU country that receives the most European money, especially in the energy sector, and it has adopted agreements to increase its competitiveness at the European level. The most recent agreement in chronological order is the one that gives Serbia access to EU research funds. This agreement will put Serbian scientific research organisations on an equal footing with those from EU member states. In addition, the Decision on the establishment of the network for the fight against fraud and irregularities in the management of EU funds was adopted, in order to improve the implementation of measures and procedures for the prevention, control, detection and punishment of irregularities and fraud in the management of EU funds.

Nevertheless, Russian vicinity is in no way diminishing. The Russian invasion of Ukraine prompted EU states to devote additional resources to developing relations with the six Balkan states of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia, despite their reluctance to further enlarge the EU.

References

- http://balkanist.net/culture-as-an-instrument-of-instrumental-political-strategy-in-russia-serbia-relations/ ↑

- https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/russias-influence-balkans ↑

- https://www.mfa.gov.rs/en/foreign-policy/bilateral-cooperation/russia ↑

- https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/srb/partner/rus?redirect=true ↑

- https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/01/03/serbia-praises-another-arms-shipment-from-russia/ ↑

- https://www.ogj.com/general-interest/article/17278484/gazprom-neft-finalizes-51-stake-in-serbias-nis ↑

- https://seenews.com/news/serbia-spends-full-amount-of-800-mln-russian-loan-for-railway-projects-591318 ↑

- https://balkaninsight.com/2014/04/30/serbia-stays-neutral-towards-ukraine-crises-dacic/ ↑

- https://www.voanews.com/a/united-states-sees-russia-humanitarian-center-serbia-spy-outpost/3902402.html ↑

- https://tass.com/defense/971755 ↑

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/stabilisation-and-association-agreement-with-serbia.html ↑

- https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-politics-europe-serbia-european-union-6deaa57230993b02e7a67f57693bf7f2 ↑

- https://euobserver.com/world/156357 ↑

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/12/28/kosovo-minister-sees-russian-influence-in-growing-serbian-tension ↑

- https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/kosovo-put-detained-serb-under-house-arrest-possibly-easing-standoff-2022-12-28/ ↑