Since 2015, when the Memorandum of Understanding on cooperation between Poland and China within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was signed, the volume of trade between the two countries has grown steadily; from $17 billion in 2017 to $49 billion in 2021. However, the exchange is characterized by a significant imbalance in the trade balance – in 2021, Polish exports to China amounted to $3.76 billion (just 1.17% of Poland’s total exports), while Polish imports from China amounted to $45.8 billion (as much as 13% of Poland’s total imports)[1]. In 2022, due to the war in Ukraine and supply chain disruptions, the Polish trade deficit narrowed slightly (from over $40 billion to around $35 billion), but it was still the third highest among European Union countries, just behind the Netherlands and Italy[2].

According to the BRI’s findings, strengthening economic cooperation was also supposed to be associated with increased FDI inflows to Poland, but so far their value leaves much to be desired. At the end of 2020, the value of Chinese FDI in Poland amounted to $2.2 billion, compared to the total value of FDI in Poland exceeding $200 billion[3]. Thus, at the economic level, Poland’s cooperation with China is still largely one-sided, where Poland acts as a sizable market for the Middle Kingdom[4].

The above patterns are also found in many other countries in the region – the total value of Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries’ exports to China was less than $25 billion in 2021, representing fewer than 20% of their total imports from China, which exceeded $125 billion. Moreover, while China exports mainly machinery and electronics, in many cases CEE countries serve mainly as China’s reservoir of natural resources – such as copper (Greece, Bulgaria), iron ore (Serbia, Macedonia) or timber (Latvia, Poland)[5].

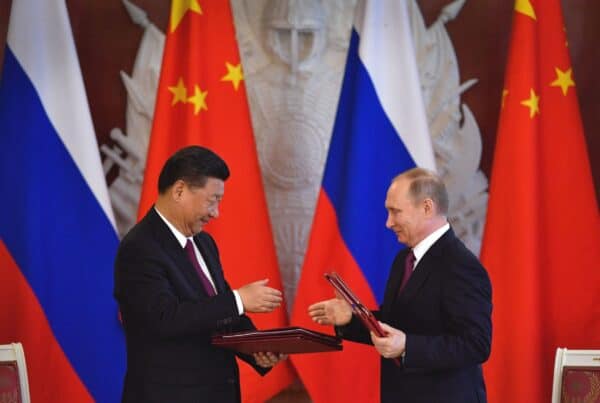

China’s relations with the CEE region have deteriorated considerably over the course of 2022 due to Beijing’s stance on Russian aggression in Ukraine, and especially in the context of Chinese political threats against countries that have chosen to prioritise relations with Taiwan – such as the Czech Senate President’s warning that he would “pay a high price” for his official visit to Taiwan, the extension of economic sanctions to Lithuania for its decision to open a Taiwanese representative office, and the spread of official Chinese propaganda through numerous Confucius Institutes. This has become a reason for the Baltic countries to leave China’s “16+1” format and discussions about taking an identical step in the Czech Republic[6].

Polish-Sino relations: an ambiguous mutuality

Despite the war across the eastern border, however, Poland’s trade relations with China have remained almost unchanged – between January and July 2023, the value of trade between the two countries reached a record $76.8 billion, Huawei’s involvement in Poland’s 5G network remains a viable scenario despite concerns over the region’s cyber-security and accusations of Chinese espionage, and a Polish-Chinese consortium recently signed another tender for the construction of an $880 million railroad line[7].

Poland also continues to be a member of the “16+1” (now “14+1”) format, despite the fact that this has so far not translated into tangible economic benefits. Although Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau and President Andrzej Duda called for China’s condemnation of Russian aggression in the 2022 space, their statements were largely soft, with a diplomatic tone[8]. It is possible that this had to do with a desire to leave themselves more room to maneuver in foreign relations with the East, wanting to gain a counterbalance to their EU partners – particularly in the context of the numerous disputes between the Polish government and Brussels, which, although left “suspended” due to the war, continue to impact the perception of Poland in Europe[9]. Thus, it can be concluded that relations between Poland and China remain positive, despite tensions over the war in Ukraine.

This could, of course, change in the event of an escalation of East-West tensions, which could occur if the Taiwan crisis were to occur, for example. In the event of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, it will be more difficult for Poland to maintain a neutral stance on the issue, given its NATO membership and alliance with the United States, which last year declared that it would defend the island “in the event of an unprecedented attack”. The outcome of October’s parliamentary elections and the declarations of the new ruling coalition about improving relations with Brussels are also not without importance, which could mean a greater degree of convergence of Polish foreign policy with its Western partners, who declare their desire for economic independence from the Middle Kingdom and an attempt to “de-risk” their supply chains[10].

The outlook for China’s trade relations with Poland thus remains ambiguous – which in a way is an asset for Poland. For as long as the darkest scenario doesn’t materialise, in which Russia wins the war in Ukraine and China, encouraged by this outcome, decides to invade Taiwan, there is little likelihood of reaching a level of tension between Beijing and the West that threatens Polish relations with China. By the same token, Poland should not completely scrap its economic ties with the Middle Kingdom. Instead of severing them completely, it can instead insure against the risk of a negative geopolitical scenario by simultaneously developing relations with other countries in the region. While the obvious directions seem to be Japan and South Korea, among others, Vietnam could become an extremely promising trade partner for Poland.

Polish-Vietnamese relations: opportunity for growth

Trade between Poland and Vietnam has grown rapidly over the past decade, although its value still does not reflect its full potential. Between 2010 and 2021, the value of Polish imports from Vietnam rose from $435 million to $2.69 billion, an increase of as much as 18% average annual growth rate. The value of Polish exports to Vietnam in the same period rose from $163 million to $626 million, increasing at an average annual rate of 13%. Despite the favorable trade dynamics, however, Vietnam is still not a key partner for Poland – accounting for 0.76% of total Polish imports and just 0.19% of Polish exports in 2021[11].

Meanwhile, Vietnam is home to nearly 100 million people, among whom a rapidly growing middle class (its share is expected to rise from 20% to 30% of the population by 2030) is responsible for growing demand for imported consumer goods[12]. Since Vietnam joined the World Trade Organization in 2007, the country has also negotiated a series of free trade agreements – initially mainly with Asian countries, but from 2020 also with the European Union, under the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA). The agreement virtually eliminates tariffs (not counting transition periods for selected goods) and significantly simplifies trade procedures, making it much easier to do business[13].

To date, Polish exports to Vietnam have been dominated by agri-food products, as reflected in the veterinary certificates obtained for poultry (July 2023) and beef (September 2023) products over the course of 2023, as well as ongoing negotiations for the terms of blueberry fruit exports (to be completed in the first half of 2024)[14]. While the efforts of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development to date in this regard should be appreciated, they should also be supported by complementary actions on the part of other ministries, increasing the export potential of the most popular Polish products, such as electrical appliances and electronics, furniture, automotive or pharmaceutical products. This is all the more promising given the perception of Polish products in Vietnam, which have made a name for themselves there as goods of European quality at competitive prices[15].

The March visit of Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau to Hanoi, where he held talks with Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh, may become a certain contribution to the intensification of business relations. At that time, the issues of creating favorable conditions for Vietnamese agricultural products in Poland and encouraging Polish companies to invest in Vietnam’s pharmaceutical, food processing and manufacturing industries were raised. Minister Rau also expressed a desire to strengthen bilateral partnerships in areas such as IT, smart cities, green technologies and environmental protection[16]. Joint ventures could become a good starting point for Polish companies planning to expand into the Vietnamese market, taking into account both the high requirements of the local bureaucracy and the country’s current development strategy, which includes demands to increase the share of medium-sized enterprises in the structure of the economy, in a bid to reduce dependence on large transnational corporations for GDP growth[17].

Concluding remarks and future prospects

In addition to favorable institutional conditions and a favorable geopolitical climate, one should also remember Poland’s positive image among the Vietnamese public. Diplomatic relations between Poland and Vietnam were established as early as 1950 (Poland was the 7th country in the world to take such a step), and during the American war in Vietnam, Polish diplomacy acted as a mediator seeking a quicker end to the conflict. Thanks to this, Poland is treated as a friendly country there, and among the Vietnamese elite one can still find numerous graduates of Polish universities from the 1970s[18]. This is one of the reasons why Poland currently has a large and friendly Vietnamese diaspora estimated at 40-50 thousand people, who often play the role of an intermediary in trade[19].

There is no doubt, therefore, that Poland should make efforts to tap the potential of the Vietnamese market and make it easier for domestic entrepreneurs to cooperate with Asian partners. Increasing the frequency of high-level delegation exchanges with Vietnam to enhance political trust and mutual understanding should therefore become part of the new government’s agenda in Poland’s foreign policy in the Southeast Asian region.

Bibliography

- Observatory of Economic Complexity. (2024). Poland – China. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/pol/partner/chn ↑

- Frączyk, J. (2023). Giant trade deficit with China. Only a few countries are worse than Poland. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://businessinsider.com.pl/gospodarka/gigantyczny-deficyt-handlowy-z-chinami-gorszych-od-polski-jest-tylko-kilka-krajow/916t2ps ↑

- Polish Investment and Trade Agency. (2024). Foreign markets – China. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://www.paih.gov.pl/rynki_zagraniczne/chiny/ ↑

- Rajca, K. (2022). Poland economy briefing: Polish – Chinese economic relations. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://china-cee.eu/2022/11/20/poland-economy-briefing-polish-chinese-economic-relations/ ↑

- European Parliament. (2018). China, the 16+1 format and the EU. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/625173/EPRS_BRI(2018)625173_EN.pdf ↑

- Hązła M., Stępniak, M. (2023). Możliwości utrzymywania stosunków dyplomatycznych z Tajwanem z uwzględnieniem kontekstu prawnego, gospodarczego i politycznego. Gdańskie Studia Azji Wschodniej, (24), 181-199. ↑

- Money.pl. (2020). The Chinese will help build Rail Baltica. The contract for 3.3 billion PLN. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://www.money.pl/gospodarka/rail-baltica-pomoga-zbudowac-chinczycy-kontrakt-na-33-mld-zl-6525689229297281a.html ↑

- wGospodarce.pl (2023). What should China do? The head of the Foreign Ministry responds. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://wgospodarce.pl/informacje/126251-co-powinny-zrobic-chiny-szef-msz-odpowiada ↑

- EGA. (2023). Poland set for pro-EU coalition government as populist right loses grip on power. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://www.edelmanglobaladvisory.com/insights/poland-set-pro-eu-coalition-government-populist-right-loses-grip-on-power ↑

- Uznańska, P. (2024). De-risking in low gear. The way forward for the EU’s economic security agenda. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2024-01-26/de-risking-low-gear-way-forward-eus-economic-security-agenda ↑

- Observatory of Economic Complexity. (2024). Poland / Vietnam. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/pol/partner/vnm ↑

- Trade.gov.pl. (2023). Vietnam is waiting for Polish products. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://www.trade.gov.pl/wiedza/w-wietnamie-czekaja-na-polskie-produkty/ ↑

- European Commission. (2024). EU-Vietnam Trade Agreement and Investment Protection Agreement. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/vietnam/eu-vietnam-agreement_en ↑

- farmer.pl. (2023). Vietnam has approved a veterinary certificate for beef imported from Poland. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://www.farmer.pl/produkcja-zwierzeca/bydlo-i-mleko/wietnam-zatwierdzil-swiadectwo-weterynaryjne-dla-wolowiny-importowanej-z-polski,136051.html ↑

- Exporter.pl. (2024). Image of Poland and Poles in the eyes of Vietnamese businessmen. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://en.vietnamplus.vn/vietnam-wants-to-strengthen-multifaceted-cooperation-with-poland-pm/249987.vnp ↑

- Vietnam Plus. (2023). Vietnam wants to strengthen multifaceted cooperation with Poland. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://en.vietnamplus.vn/vietnam-wants-to-strengthen-multifaceted-cooperation-with-poland-pm/249987.vnp ↑

- McDonald, R. (ed). (2020). The Economy and Business Environment of Vietnam. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ↑

- Gov.pl. (2024). Polish – Vietnamese bilateral relations. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://www.gov.pl/web/wietnam/relacje-dwustronne ↑

- Polish Ministry of Development and Technology. (2022). New Perspectives on cooperation with Vietnam. Accessed 19.02.2024 at: https://www.gov.pl/web/rozwoj-technologia/nowe-mozliwosci-wspolpracy-z-wietnamem ↑