Jan Normann – University of Wrocław

Jan Normann is a third-year undergraduate student at the University of Wrocław, Poland, majoring in European Studies. Since March, he has interned at Blue Europe, serving as a Public Relations Intern. Jan is also a dedicated member of the Forum of Young Diplomats in Poland and contributes actively to the university’s academic society, Project Europe. He organizes significant events such as recent pre-election debates for the European Parliament. His international experience includes a year on the Erasmus+ exchange at Ben-Gurion University in Beer Sheva, Israel, and serving as an assistant to the Honorary Consul of Poland in Jerusalem, Zeev Baran. He participated in an international research team studying the impact of foreign powers on elections in European countries through social media platforms in 2023. Jan has also interned at the Polish Culture Institute in Paris and attended a week-long course focused on Ukraine in Covilhã, Portugal. His primary interest lies in diplomacy, particularly EU-Middle East relations.

1. Definition of security within the EU

Since the beginning of the European Union, the issue of security has been one of the most important when it comes to giving shape and functioning to the EU. Even before the 1992 Maastricht Treaty during the so-called Cold War, European countries knew they needed each other to repel the threat from the East. In addition to economic and political integration, the defensive aspect was also important, as manifested in the Western European Union, which served as the European Defense Community until the Lisbon Treaty came into force in 2010. Since then, the defence issue has been integrated into the Common Foreign and Security Policy. However, it must be stressed that defence issues, as well as security issues, are the prerogative of states, so the Lisbon Treaty aims to increase cohesion and capabilities but does not in any way interfere with the behaviour of member states[1]. Moreover, it is worth emphasizing that the European Union was created as a socio-economic organization, so today security in Europe is not only about avoiding war and violence through the use of military instruments. It encompasses social and even individual dimensions, as well as economic, environmental, criminal, humanitarian and human rights issues, as well as those related to the unauthorized use of violence[2]. To emphasize, the individual EU countries look after their own security and defence interests. Geographically speaking, in fact, it is not possible to have the same interest from Lisbon to Tallin. Therefore, it is worth defining and analyzing security issues using the examples of two of largest EU countries, France and Poland, which have different geographic and strategic interests and, above all, security.

2. A brief overview of France’s security interests in the European Union

In France, there isn’t a singular, static perspective, but rather a dynamic amalgamation of viewpoints stemming from various ideological factions. This results in a constantly evolving national stance, influenced by different administrations and historical contexts. Despite occasional misunderstandings with European allies, France’s defence administration operates along two main lines of thinking: one emphasises political-military relations with a bilateral focus, while the other prioritizes diplomacy with a Euro-centric approach. These perspectives, more akin to strategic dispositions than rigid doctrines, shape how France navigates global challenges and relationships[3]. Referring to the 2021 document defining France’s challenges, there are indications that it is looking at security from a global perspective. France faces ongoing threats to its interests, including jihadist terrorism, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and strategic competition between major powers. Russia and China have intensified their military capabilities, prompting a response from the United States. Regional powers in the Middle East and Mediterranean, emboldened by global power shifts, are asserting themselves more aggressively. Hybrid strategies, combining military and non-military tactics, are on the rise. The international order is fragmenting, with Europe’s security architecture weakening. France is adapting its defence strategy, focusing on cyber, space, AI, and energy. Strengthening European sovereignty and defence autonomy is crucial, along with enhancing national resilience. Future challenges require continued modernization and scaling up of defence capabilities. Ambition 2030 aims to ensure France’s security and autonomy in an increasingly complex geopolitical landscape[4]. It is worth noting that France has historical interests that it still cultivates today. This is due to its colonial history, as well as its influence in the Mediterranean, Africa and the Middle East. Therefore, an Eastern European perspective is inherently foreign to Paris. Additionally, under Macron’s presidency, Franco-German relations have become the most important format for cooperation[5]. Moreover, after Britain’s exit from the European Union in 2020, France has become the leader and, next to Germany, the most powerful country in the EU. Therefore, the EU’s foreign policy interests are inextricably linked to the French perspective.

3. A brief overview of Poland’s security interests in the European Union

When analyzing Polish security interests in the 21st century, it should be noted that Poland is in a difficult position being on the eastern flank of the EU, which poses a serious defence challenge. Russia is expanding its power, which threatens its security[6]. In such a situation, there is an opportunity to create a bridge between East and West and take a leading role in the region. Poland is active in the Visegrad Group format, and since the end of 2023, it has also increased its activities in the Weimar Triangle format. In addition, in the broader picture of the 21st century, Poland has been trying to draw the attention of the rest of Western Europe to the regional problems and to participate in cooperation initiatives such as the Lublin Triangle and the reactivation of an historical idea, the so-called ‘Trimarium’, which was intended to emphasize the importance and establish deeper cooperation in the area of Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans. To elaborate further, in 2015, the Trimarium Initiative Group was founded by the presidents of Poland and Croatia, with its inaugural summit held in Dubrovnik on August 25-26, 2016. Eastern European leaders at the summit endorsed a declaration outlining cooperation goals in energy (specifically diversification of gas supplies), transportation, and digital communications. They believed that achieving these goals would enhance security and competitiveness in Eastern Europe, thereby strengthening the European Union[7]. There is no denying that Poland’s position was not very strong during the first two decades of the 21st century. Many initiatives were not effective or are, as of today, still in their infancy. Compared to France, Poland is undoubtedly a local player, which, together with other Central and Eastern European countries, is trying to find a counterweight to what is often referred as the “centre” of the European Union, France and Germany.

4. Different security interests’ approaches between Poland and France within the European Union

In France, the approach to security within the European Union is characterized by political-military relations with a bilateral focus, while others prioritize diplomacy with a Eurocentric approach. France’s security interests are intertwined with its historical interests, colonial history, and influence in regions such as the Mediterranean, Africa, and the Middle East. Under Macron’s presidency, Franco-German relations have become the cornerstone of cooperation, and France has emerged as a key leader in the EU following Britain’s exit[8]. Therefore, France’s perspective on EU foreign policy is closely aligned with its interests, emphasizing a balance between bilateral relations and a Euro-centric approach. Finally, it should be noted that both countries through the 21st century had different perceptions of the East, and above all of Russia, which for Poland is the main enemy and entity with which it competes in the eastern part of Europe. On the other hand, France has not had a negative experience of relations with Moscow, so the relationship has generally been correct and a partnership, especially on political as well as economic issues.

Poland’s security approach within the European Union is shaped by its unique position on the eastern flank, which presents significant defence challenges due to Russia’s expanding power. Poland seeks to play a leading role in the region by fostering cooperation initiatives such as the Visegrad Group and the Weimar Triangle. Additionally, Poland aims to draw attention to regional issues and participate in initiatives like the Lublin Triangle and the Trimarium[9], emphasizing cooperation in Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans. Unlike France, Poland’s focus within the EU is more localized, as it strives to find a counterweight to the dominance of countries like France and Germany. Poland’s security interests are primarily centred on addressing regional threats and enhancing cooperation within its immediate vicinity, reflecting a more regional and focused approach compared to France’s broader strategic outlook within the EU. An important highlight is the approach to security, as Poland has a land border with Russia, Belarus and Ukraine with a length of about 1186 km. That’s why it sees the situation in the east, and even more so Russia, as a real and immediate security threat. Poland feels a more immediate threat to its territory than Germany and France, so the approach to this issue is met with different intensity and solutions.

5. The war in Ukraine as a turning point in the context of the unification of Polish and French security interests within the EU

The war in Ukraine was a turning point in the context of the unification of Polish and French security interests within the European Union. In the case of Poland, it is worth noting Poland’s increased strategic importance in Europe. Most experts agree that the Russo-Ukrainian war has increased Poland’s significance in Eastern Europe for several reasons[10]. Poland accurately recognized the threat from Russia, which, combined with its favourable geographical location, allowed it to shield the rest of the region and support Ukraine. Additionally, there was a convergence of interests between Poland and the main Western powers, particularly the USA. However, experts emphasize that this situation may be temporary. Poland has temporarily become a “security hub” due to three main processes: support from the USA and NATO, including counterintelligence protection and NATO military transport support; substantial humanitarian aid to Ukraine, including the acceptance of several million refugees; and significant military assistance to Ukraine, including equipment and training for Ukrainian forces. Poland’s position has been strengthened by a temporary political consensus in the country around these processes. Experts recommend that Poland increase its “geopolitical dividend” resulting from its international roles. However, they are sceptical about Poland’s rapid ability to influence other countries. It is observable that the time of war represents a unique “window of opportunity” for Poland, which should be utilized. It is a chance for a “fresh start” in terms of external security and preparing Poland for long-term changes in international power dynamics in the region. Experts emphasize that security policy has become one of the priorities of the Polish government in 2022. Work on defence reform has been accelerated, a weapons program has been announced, and an increase in defence spending and the size of the armed forces has been promised. At the same time, the presented bill on population protection has been criticized by experts and public opinion. Poland and Ukraine are embarking on a new chapter in their relations, opening up[11]

On the other hand, from neutral and good pre-war relations with Russia, France has changed its rhetoric 180 degrees by antagonizing, criticizing Moscow and fully supporting Ukraine.[12] However, Paris’ much more radical stance toward Russia can be seen more recently, 2 years after the beginning of the most destructive war on the continent since World War II. This is because attempts for dialogue and de-escalation with Russia have failed.[13] The attitude of the United States, and in particular the delayed aid procedure from Congress, also began to be an important issue.[14] The turning point was the signing of a security cooperation agreement between France and Ukraine in February 2024. It was a key decision that included bilateral cooperation and €3 billion in aid. The agreement aimed to help Ukraine restore its territorial integrity within internationally recognized borders and prevent any renewed aggression by Russia[15]. “The outcome of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine will be decisive for our interests, our values, our security and our model of society,” Macron said[16]. However, many countries in Central and Eastern Europe, including Poland, there is scepticism over the fact that France has had a long, traditional[17]. An opportunity to change this attitude was seen after the change of government in Poland in December 2023. One of Warsaw’s major foreign policy decisions was the resumption of talks and cooperation within the Weimar Triangle, a significant change in the context of European cooperation over the past eight years.

6. Resumption of cooperation within the Weimar Triangle

The Weimar Triangle is a format of Polish, German and French cooperation set up in 1991. From the beginning, the premise of the format was to be political dialogue and cooperation, but it has not been a very popular format since its inception. For the past eight years, Poland has not used this option, basing its security position on relations with the US, while France and Germany have close bilateral relations. The new situation of war in Europe and the search for a counterweight led these countries to resume talks within the format.[18]

Tusk’s visit was accompanied by a meeting at the La Celle-Saint-Cloud castle near Paris of the foreign ministers of Poland Radoslaw Sikorski, France Stephan Sejournei and Germany Annalena Baerbock. The Polish head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs already spoke in January about renewing the Weimar Triangle formula. A declaration was signed reaffirming the commitment of France, Germany and Poland to work together to promote peace and stability in Europe.[19] It emphasizes the principles of democratic security, pledging to strengthen the NATO alliance through a commitment to a European defence initiative and joint foreign policy action.

Poland’s prime minister has made it clear that the country is determined to work closely with its two largest European partners in an attempt to also break the deadlock in bilateral Franco-German relations. It is no secret that Olaf Scholz and Emmanuel Macron have not stepped up to the level of the once all-powerful tandem led by Angela Merkel and successive French leaders. That tandem had its flaws and its decisions were often rightly criticized for ignoring the interests and sensitivities of smaller partners. However, the Franco-German partnership had a leading role in the EU and gave the Union direction. Working together with pro-European Poland in the Weimar Triangle, the Franco-German engine can again work for the good of the EU as a whole. Tusk’s experience, first as prime minister and later as president of the EU Council, is an asset here – he knows how to forge a European consensus with the necessary participation of Germany and France while respecting the interests of smaller member states.[20]

Observable is that there is another dimension to this cooperation, which is contained within NATO. When looking at Europe’s 2023 defense spending, Poland, France and Germany show the largest expenditure, which is crucial in the current situation.

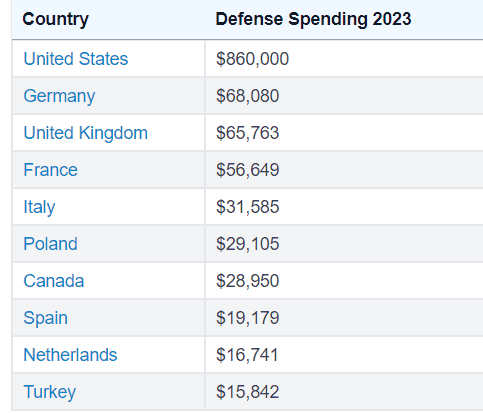

Table 1. Top 10 NATO defense spending countries in the year 2023 (in USD)

Source: Top 10 NATO Countries with the Highest Defense Expenditures (by total US$).[21]

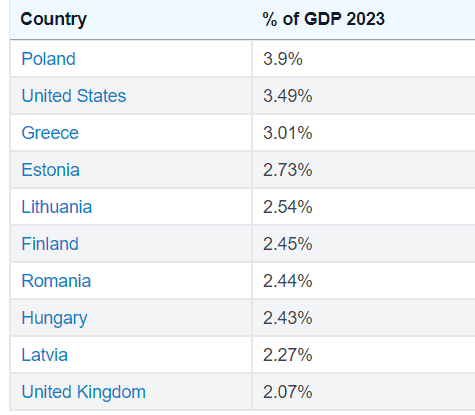

Table 2. Top 10 NATO defense spending countries in the year 2023 as percentage of GDP

Source: NATO Spending by % of GDP 2023.[22]

As it can be observed in Table 1, France, Germany and Poland are among the top ten countries spending the most on defence. On the other hand, Poland spends the highest percentage of GDP on defence at 3.9% Table 2. This is the highest percentage in NATO, and the country often “turns up the heat” and encourages the rest of the European countries to exceed the 2% ceiling, something Germany and France is not currently doing. However, taking everything together, it can be seen that cooperation between these countries on security issues can be beneficial.

Now the strengthening of relations continues, as further regular meetings of the three countries’ foreign ministers have been announced. Another example of the resumption of cooperation was the sudden Weimar Triangle summit in Berlin on March 15. Donald Tusk, Olaf Scholz and Emmanuel Macron met in Berlin. The Weimar Triangle format discussed the future of the war in Ukraine as the Polish head of government returned from a meeting with Joe Biden in Washington, which was so important to share with European partners. The German chancellor conveyed that the allies will purchase more weapons for Ukraine on “world markets.” The French president emphasized that “European security is at stake,” and the Polish prime minister stressed that the three countries “speak with one voice.” “This is a good new beginning for the Weimar Triangle,” he furtherly assessed[23].

Observing recent developments, one can point to the complement of Macron’s anti-Russian rhetoric toward Russia. In February of this year, after a meeting of heads of state and government in Paris, French President Emmanuel Macron said that “there is no agreement at this stage to send troops to Ukraine,” adding, however, that “nothing can be ruled out.” The statement sparked considerable controversy among NATO leaders[24]. This is the first time a European leader has loudly and firmly considered sending troops to Ukraine. This was met with a response from the Polish side. A day later after Macron’s statement, during a conference of the Polish and Czech prime ministers, Donald Tusk addressed the words: “I think we should not speculate today about the future, or whether there will be circumstances that will change this position,” emphasized. “Today we should focus, as the Polish or Czech governments do, on supporting Ukraine to the maximum in its military effort,” continued the head of the Polish government. “I don’t want this to sound too harsh, but if all the countries of the European Union were as engaged in helping Ukraine as Poland and the Czech Republic are, perhaps there would be no need to discuss other forms of support for Ukraine,” added Tusk[25].

7. Conclusion

France and Poland, as two very different countries with different geopolitical and strategic interests, have found common ground in the perspective of European security interests. Following completely different paths, the war in Ukraine made it necessary to go into the Europeanization and not the nationalization of the security interest. This is also important because they are one of the larger countries in the European Union and the most significant. Of course, the approach will differ all the time, as the ultimate goal for Poland is to ensure a decisive defeat for Russia in Ukraine. Poland’s geographical position and historical context have led to a firm dedication to securing an unequivocal military triumph for Ukraine. Meanwhile, France prioritizes managing escalation and shaping the future framework of European security[26]. Moreover, it is worth emphasizing that as long as cooperation within the Weimar Triangle continues to grow, and as long as countries from Paris to Warsaw tighten relations and cooperation, it will lead to an overall increase in security in Europe, as a full complement to the American component in European security and defence interests. I would add that if these two countries develop their relations and together with Berlin build a sustainable core of Europe this will be a long-term solution and will not only be in the context of the war in Ukraine but also in the context of other challenges that await the EU, including the increase in illegal migration, potential terrorism, economic issues and relations with other countries.

References

-

Menon, A. (2011). Much ado about nothing: EU defence policy after the Lisbon treaty, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anand-Menon/publication/228715077_Much_Ado_About_Nothing_EU_Defence_Policy_after_the_Lisbon_Treaty/ ↑

-

Deighton, A. (2002), The European Security and Defence Policy. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 40: 719-741. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00395 ↑

-

De France, O. (2019). The French Perspective. Armament Industry European Research Group, https://preprod.iris-france.org/ ↑

-

Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, (2021). Defence – 2021 strategic renewal/summary – Communiqué issued by Mme Florence Parly, Minister for the Armed Forces, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/security-disarmament-and-non-proliferation/news/article/defence-2021-strategic-renewal-summary-communique-issued-by-mme-florence-parly ↑

-

Kempin, R. (2021). France’s foreign and security policy under President Macron: The consequences for Franco-German cooperation, https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2021RP04/ ↑

-

Antczak-Barzan, A. (2014). Rangi wyzwań dla bezpieczeństwa Polski w XXI wieku, Studia Politologiczne, 34, 226-240, http://www.studiapolitologiczne.pl/pdf ↑

-

Baziur, G. (2017). Trójmorze jako koncepcja bezpieczeństwa i rozwoju ekonomicznego Europy Wschodniej, Przegląd Geopolityczny, (23), 24-38, https://www.ceeol.com/search/viewpdf ↑

-

Kempin, R. (2021). France’s foreign and security policy under President Macron: The consequences for Franco-German cooperation, https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2021RP04/ ↑

-

Baziur, G. (2017). Trójmorze jako koncepcja bezpieczeństwa i rozwoju ekonomicznego Europy Wschodniej, Przegląd Geopolityczny, (23), 24-38, https://www.ceeol.com/search/viewpdf ↑

-

Pawłuszko, T. (2023). Polityka bezpieczeństwa Polski-wnioski z badań empirycznych, Przegląd Geopolityczny, (43), 49-70, https://www.ceeol.com/search/viewpdf?id=1223204 ↑

-

Ibidem, https://www.ceeol.com/search/viewpdf?id=1223204 ↑

-

Kapp, C. L., & Fix, L. (2023). German, French, and Polish Perspectives on the War in Ukraine, In Polarization, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376852587_German_French_and_Polish_Perspectives_on_the_War_in_Ukraine ↑

-

Świerczyński, M., & Tenenbaum, E. (Hosts). (2024). Spokojnie czy przedwojennie? PI Podcast, In Polityka Insight, https://www.politykainsight.pl/nowa/podcast, [41:00-50:00]. ↑

-

Ibidem, https://www.politykainsight.pl/nowa/podcast, [41:00-43:00]. ↑

-

Le Monde (2024). Zelensky signs security agreement with France, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/europe/article/2024/02/16/zelensky-signs-security-pact-with-france ↑

-

Moulson, G., & Corbet, S. (2024). Ukraine’s Zelenskyy in Paris signed a security agreement with France after a similar deal with Germany, AP News, https://apnews.com/article/germany-france-ukraine-zelenskyy-security ↑

-

Świerczyński, M., & Tenenbaum, E. (Hosts). (2024). Spokojnie czy przedwojennie? PI Podcast, In Polityka Insight, https://www.politykainsight.pl/nowa/podcast, [46:30-48:00]. ↑

-

Zaremba, M. (2024). Świat dostrzegł wizytę Tuska w Paryżu i Berlinie. “Reaktywacja Trójkąta Weimarskiego”, Wprost, https://www.wprost.pl/polityka/11582203/wizyta-tuska-w-paryzu-i-berlinie-zauwazona-czym-jest-trojkat-weimarski.html ↑

-

Ibidem. ↑

-

Przybylski, W. (2024), Nowy impuls dla Trójkąta Weimarskiego, Opinie Polityczno-Społeczne, Rzeczpospolita, https://www.rp.pl/opinie-polityczno-spoleczne/art39856621-wojciech-przybylski-nowy-impuls-dla-trojkata-weimarskiego ↑

-

https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/nato-spending-by-country ↑

-

Ibidem. ↑

-

asty/ft, adso, mrz, (2024). Nagły szczyt Trójkąta Weimarskiego. Scholz, Tusk i Macron o zakupach broni dla Ukrainy z zamrożonych rosyjskich pieniędzy, TVN24 Świat, https://tvn24.pl/swiat/trojkat-weimarski-nagly-szczyt-donald-tusk-olaf-scholz-i-emmanuel-macron-rozmowy ↑

-

ks/tok, Macron o wysłaniu wojsk na Ukrainę, “gdyby Rosjanie się przedarli”, TVN 24, 2024, https://tvn24.pl/swiat/ukraina-rosja-macron-o-wyslaniu-wojsk-na-ukraine-gdyby-rosjanie-przedarli-sie-przez-linie-frontu-st7897742 ↑

-

tas, Tusk: Polska nie przewiduje wysłania żołnierzy na Ukrainę, TVN 24, 2024, https://tvn24.pl/swiat/ukraina-emmanuel-macron-o-mozliwosci-wyslania-zolnierzy-na-ukraine-donald-tusk-polska-tego-nie-przewiduje-st7793577 ↑

-

Kapp, C. L., & Fix, L. (2023). German, French, and Polish Perspectives on the War in Ukraine, In Polarization, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376852587_German_French_and_Polish_Perspectives_on_the_War_in_Ukraine ↑