This contribution is part of the book “The Dragon at the Gates of Europe: Chinese presence in the Balkans and Central-Eastern Europe” (more info here) and has been selected for open access publication on Blue Europe website for a wider reach. Citation:

Hazla, Marceli, Opportunities for Three Seas Initiative countries for maintaining diplomatic relations with Taiwan, in: Andrea Bogoni and Brian F. G. Fabrègue, eds., The Dragon at the Gates of Europe: Chinese Presence in the Balkans and Central-Eastern Europe, Blue Europe, Dec 2023: pp. 57-98. ISBN: 979-8989739806.

1. Introduction

Since 1971, when representatives of the Government of the Republic of China in exile were stripped of their exclusive rights to represent China in the UN General Assembly which were then handed over to the Chinese Communist Party, Taiwan’s status has remained unresolved. Taiwan is currently not represented in the United Nations or its affiliated organisations, making it difficult for the Taiwanese government to pursue its foreign policy and international cooperation objectives. However, as will be outlined in this chapter, Taiwan’s current status quo is not only related to legal issues, but also depends heavily on economic conditions and political arrangements. As a result of Chinese economic and political pressure, Taiwan’s geopolitical situation is somewhat reminiscent of that of the Three Seas Initiative countries that are in the former Soviet sphere of influence, to which the current aggressive Russian foreign policy refers[1].

The aim of this chapter will be to present the opportunities for Three Seas Initiative (TSI) countries[2] to maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan, taking into account the legal, economic and political context. This approach is inspired by the theory of institutional economics, according to which the final political arrangements are derived from the legal and economic conditions[3], which helps to clarify certain issues in international relations[4] – in this case, the status quo of Taiwan. Therefore, despite the existence of a significant number of studies touching on the issue of Taiwan’s international legal status, this publication aims to bring a slightly different perspective to the discussion on it than has been done so far. The chapter is divided into four parts. In the first part, the historical context of Taiwan’s international status is presented, taking into account the legal conditions for maintaining diplomatic relations. Parts two and three present the economic and political conditions for maintaining diplomatic relations with Taiwan, both in general terms and with regard to the specificities of the TSI countries. The subject of part four are the perspectives of TSI countries for maintaining diplomatic relations with Taiwan in light of the arguments raised earlier. The research method adopted is a qualitative analysis of statistical data, literature and press reports. The temporal scope of the study is 1912-2023 in relation to the historical introduction, but the main focus is on the 21st century due to the greater availability of data.

2. Historical context and legal conditions for establishing and maintaining diplomatic relations with Taiwan

Due to numerous historical circumstances that took place between 1912-1951, the international legal status of Taiwan remains unresolved[5]. Following the retreat of the Republic of China (ROC) authorities to Taiwan in 1949, the dual representation of China has been discussed on many occasions – unfortunately without success. Indeed, both People’s Republic of China (PRC) and ROC were equally adamant that their representation was the only legitimate representation of the whole of China[6]. Faced with the impossibility of forging a compromise, the UN General Assembly finally adopted Resolution 2758 on 25 October 1971, which led to the expulsion of ROC from the United Nations and all other related organisations[7].

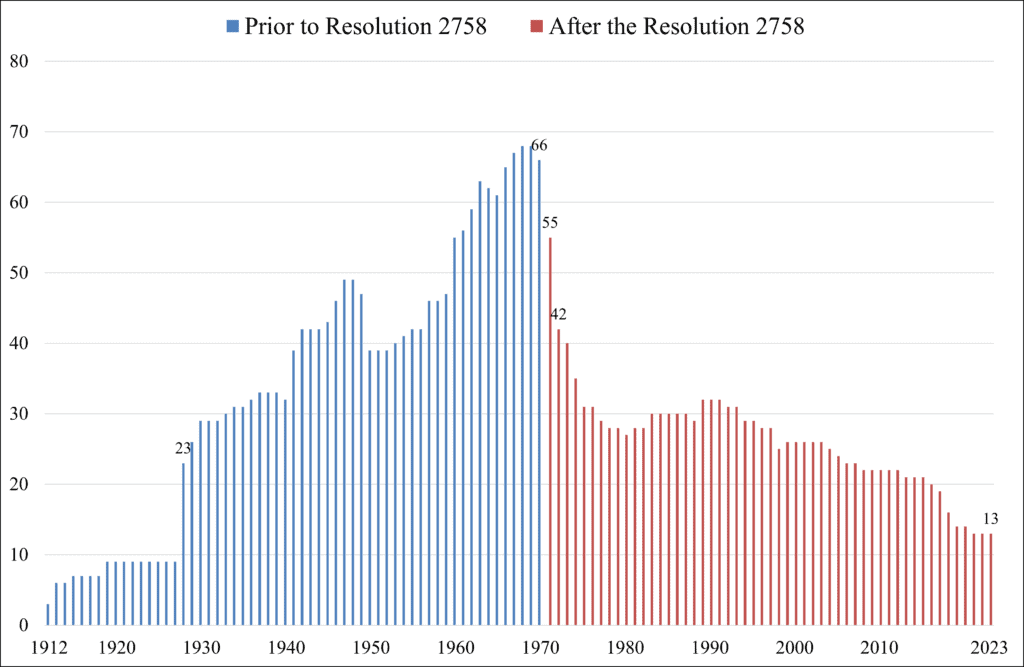

In order to better illustrate the varying recognition of ROC, it is worth referring to the number of states recognising it over the years (Figure 1). After a significant increase in 1928 as a result of the establishment of relations with the United States, and thanks to the increasing number of states joining the United Nations in the wake of post-war decolonisation, ROC managed to maintain a high level of international recognition for two decades after the breakaway from mainland China in 1949. In 1968, the number of states recognising ROC reached a record high of 68 entities, which at the time represented the majority of UN member states. As a direct result of the adoption of Resolution 2758 in 1971, however, a downward trend began among the number of countries recognising ROC in international relations – from 66 in 1970 to 42 in 1972. The following decades were also associated with PRC’s growing importance in the international arena as a result of the reforms of Deng Xiaoping and his successors, which opened the country to foreign investment and trade[8]. Thus, in 2023, only 13 countries in the world maintains official diplomatic relations with the Republic of China[9].

Despite its low level of official international recognition, Taiwan[10] nevertheless maintains numerous unofficial relations with 59 UN member states, 3 territories (Guam, Hong Kong and Macao) as well as all member states of the European Union[11]. In this way, it has a total of 110 representations, which ranks it 31st in the world in terms of the size of the diplomatic network it maintains[12].

Figure 1: Number of countries recognising the Republic of China (Taiwan) in international relations from 1912 to 2023

Source: World Population Review, Countries that Recognize Taiwan, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-that-recognize-taiwan [accessed 02.03.2023].

This provides an important starting point for the discussion of Taiwan’s recognition under international law. In the context of the basic requirements necessary for an entity to be considered a state, the most commonly adopted point of reference is 1933 Montevideo Convention, which laid the foundations for what is now the most popular state recognition practice – according to which, a state must have a permanent population, a defined territory, a government and the capacity to conduct international relations[13]. While the ability to meet the last criterion in the case of Taiwan is limited due to the non-admission of its representatives to the UN, the Convention does not specify the exact means of conducting diplomatic relations. Hence, maintaining unofficial diplomatic relations with a number of countries through numerous ‘Bureaus of Economy, Trade and Culture’ and other think tanks instead of traditional embassies and consulates is a sufficient form of meeting this criterion[14]. It is also worth addressing the issue of the national identity of the people of Taiwan. According to Article 1 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, “All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development”[15]. Article 3 of this Covenant also clarifies that “The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to ensure the equal right of men and women to the enjoyment of all civil and political rights set forth in the present Covenant”[16]. This is particularly significant in light of the fact that, among those living in Taiwan, the number of people identifying themselves solely as Taiwanese has increased from 17.6% in 1992 to 60.8% in 2022, while the number of people identifying themselves as Chinese has decreased from 25.5% to 2.7% over the same period[17]. This makes it clear that Taiwanese citizens are increasingly emphasising their distinct national identity, which is different from that of Chinese citizens – hence their right to self-determination. As China has been a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights since 1998[18] this means that its denial of Taiwan’s right to self-determination is a violation of international law, given the wording of Article 3. Another topic worth mentioning in this regard are the actual intentions of the UN member states when they voted in favour of Resolution 2758. According to its wording, the General Assembly intended only to grant the People’s Republic of China a seat occupied by the Republic of China in the General Assembly and the Security Council, as reflected in the official historical records and meeting minutes[19]. However, the resolution did not resolve other issues, such as Taiwan’s independent participation in UN bodies – and so the United Nations is legally free to recognise that Taiwan has all the characteristics of statehood and accept it as a new member[20]. This is particularly important given the current lack of official representation of Taiwan’s population in the UN and related organisations. Indeed, according to Article 1 of the Charter of the United Nations, the main objectives of the Organisation are to maintain international peace and security, to develop friendly relations among nations and to solve problems through international cooperation[21]. Denying Taiwan the right to represent its nearly 24 million population[22] within the General Assembly, and thus significantly impeding its ability to pursue these objectives, is therefore a clear denial of the values underlying the entire United Nations. Hence, as Anthony Blinken has aptly observed, “Taiwan’s exclusion undermines the important work of the UN and its related bodies”[23].

3. Economic conditions

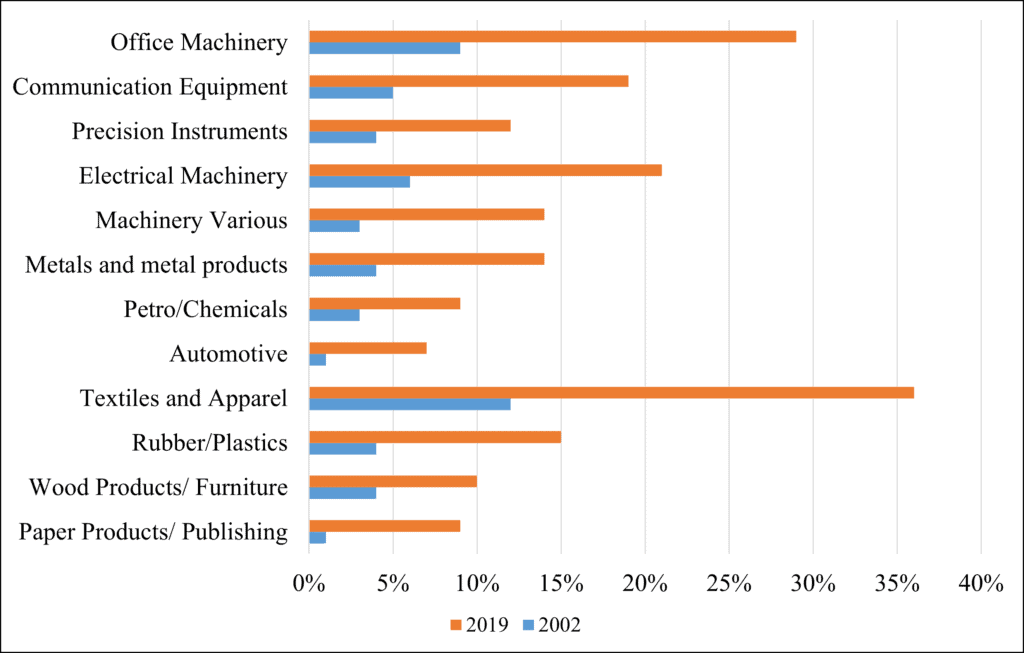

The vast majority of countries do not currently recognise Taiwan in official diplomatic relations, as this would risk a retaliatory break in relations by the Chinese side, in line with the Chinese Communist Party’s ‘One China’ policy. Such outcome would be undesirable for most economies due to China’s growing importance in the international arena. Between 1978 and 2020, China’s share of total world merchandise exports increased from 0.8 % to 14.7 %, which is currently the highest in the world and almost double the share of the second-placed United States (8.1 % in 2020)[24]. At the same time, China’s share of global exports of parts, components and intermediates, which are most used by industrialising and emerging economies, has also increased significantly – in many sectors it amounts to several percent, even reaching a record 36% in the case of textiles and clothing (Figure 2). Thus, a growing number of countries are becoming closely linked economically with China, forcing positive diplomatic relations with the PRC[25].

In this situation, certain key strategic points are therefore of increasing importance in the international arena, due to their raw material, economic, technological or geopolitical potential. Taiwan is one such point, which is related to its key role in global high-tech value chains. Founded in 1987, the state-owned TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) has over the past decades become the world’s most technologically advanced company in the industry, responsible for the production of a significant proportion of the most advanced microchips that are now the backbone of modern developed economies[26].

Figure 2: China’s share of global exports of parts, components and intermediates by sector in 2002 and 2019

Source: C. Razo, China’s participation in global value chains, ‘Flourish’, 03.05.2021, https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/5871475/ [accessed 07.03.2023].

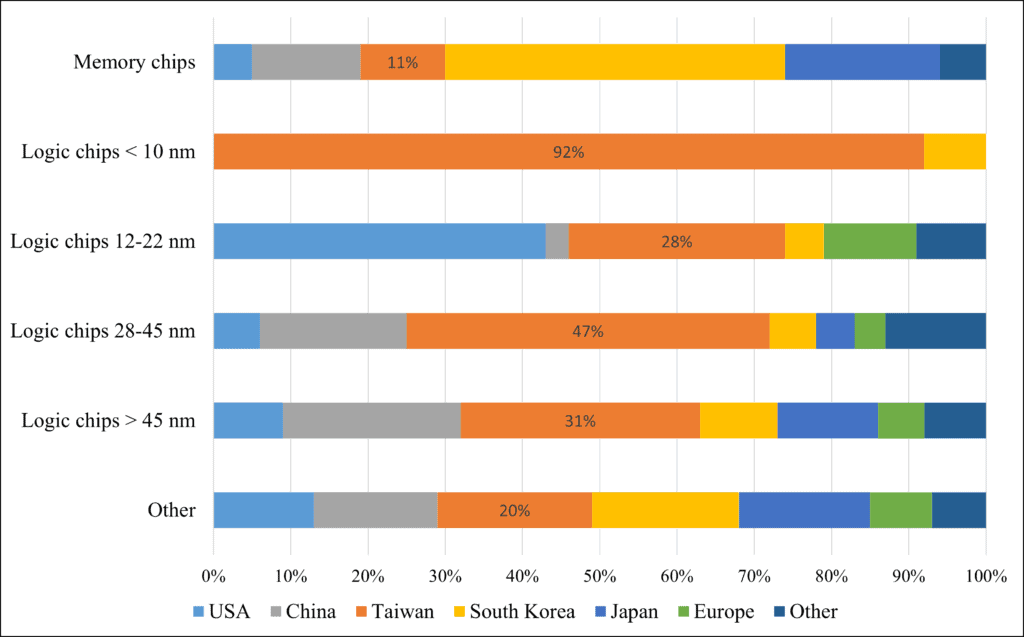

At the same time, the level of concentration in the microchip market is becoming a source of increasing anxiety and tension. Indeed, due to the multitude of applications and the growing number of industries dependent on their production, microchips have become a strategic industry. Meanwhile, 90 per cent of all memory chips and 75 per cent of logic chips are produced in East Asian countries, particularly Taiwan (20 per cent) and South Korea (19 per cent)[27]. Taiwan is also the almost exclusive producer of the most advanced microchips with transistor spacing of less than 10 nanometres, accounting for 92% of their global production (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Global chip production by region, 2019

Source: Boston Consulting Group & Semiconductor Industry Association, Strengthening the Global Semiconductor Supply Chain in an Uncertain Era, Boston, Massachusetts 2021, p. 35.

The level of these tensions could be seen in full force for the first time in 2018-2019, when the US entered into a trade conflict with China after imposing tariffs of several per cent on nearly USD 0.5 trillion worth of goods[28]. Regardless of the economic impact of the conflict, according to many authors, it became a major turning point in China-US relations, from which China began to challenge US hegemony more forcefully and openly, and to aspire to achieve technological supremacy[29]. For this, however, it will be necessary for China to gain control of Taiwan, given its aforementioned key role in the chip market.

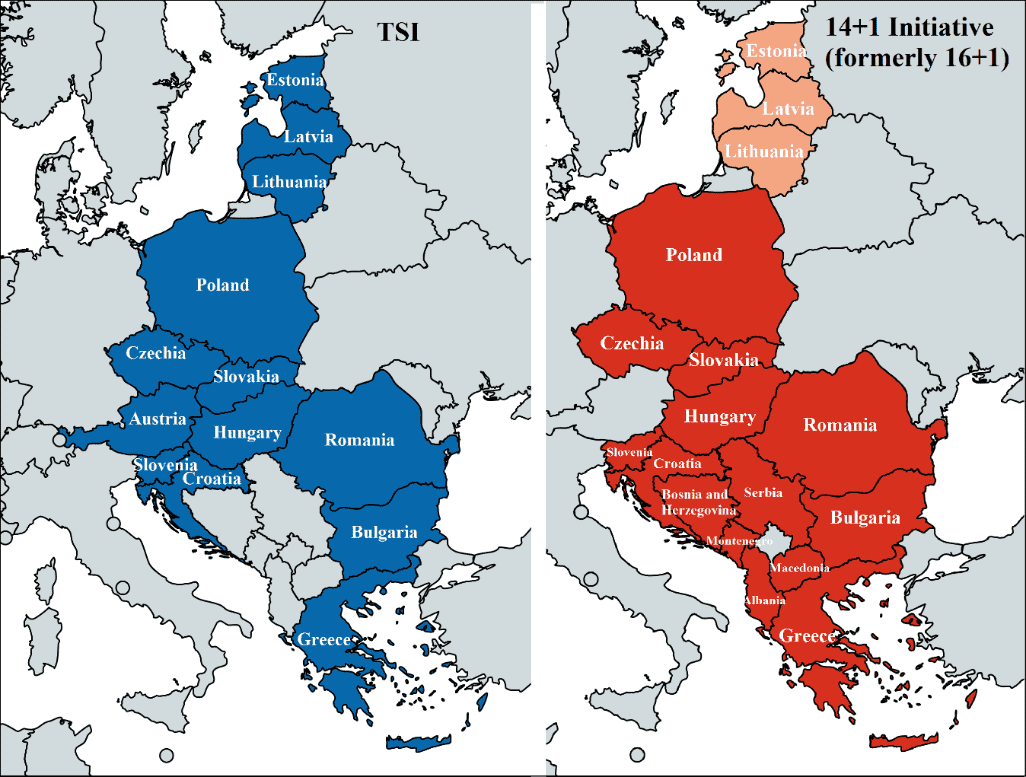

Considering the broader context of the rivalry between the US and China, the TSI countries are a particularly interesting case. The Three Seas Initiative was warmly welcomed by the US given its potential to limit Chinese influence in the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) region and is sometimes referred to as the “American Silk Road”[30]. The growing importance of the region is illustrated by the fact that back in 2012 China established the 16+1 (now 14+1) Initiative, aiming for it to be a “bridge in terms of Eurasian connectivity, and achieve an advanced level of political coordination and reciprocal comprehension between Beijing and 16 Central and Eastern European Countries in areas of infrastructure, high and green technologies”[31], and the set of countries included in both initiatives was relatively similar[32] (Figure 4).

Figure 4: TSI countries and 14+1 Initiative countries

Source: MapChart, https://www.mapchart.net/europe.html [accessed: 05.10.2023].

However, after a decade of cooperation, criticism of the format promoted by China began to emerge, given the unequal distribution of its benefits[33]. Indeed, Central and Eastern European countries served as an extension of the Central State’s economic sphere of influence without receiving the expected FDI inflows in return (Table 1).

It can be observed that Chinese FDI in the CEE region amounted to less than USD 11 billion between 2012 and 2020, compared to USD 205 billion of total FDI inflows between 2010 and 2019. Annual average Chinese FDI inflows as % of annual average total FDI inflows also shows that for most countries in the region (with the exception of Hungary and Serbia) Chinese investment was not an important source of FDI. Another problem with the Chinese FDI is how their nature has evolved. The first wave of Chinese investment in the CEE region between 2010 and 2014 was mostly greenfield in nature[34], however in the following years the FDI stream become more brownfield-oriented, especially in telecommunication and other digital industries[35].

Table 1: Chinese FDI inflows in comparison to total FDI inflows to 16+1 Initiative countries, 2012-2020

| Country | Total FDI inflow, 2010-2019 (mln USD) | Annual average total FDI inflow (mln USD) | Chinese FDI inflow, 2012-2020 (mln USD) * | Annual average Chinese FDI inflow (mln USD) | Annual average Chinese FDI % of annual average total FDI |

|

Albania |

5 556 |

694.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.00 % |

|

Bosnia-Herzegovina |

2 046 |

255.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.00 % |

|

Bulgaria |

6 886 |

860.8 |

450.0 |

56.3 |

6.53 % |

|

Croatia |

-2 349 |

-293.6 |

311.3 |

38.9 |

n/a |

|

Czechia |

42 178 |

5 272.3 |

362.0 |

45.3 |

0.86 % |

|

Estonia |

11 925 |

1 490.6 |

66.3 |

8.3 |

0.56 % |

|

Hungary |

6 826 |

853.3 |

2 572.5 |

321.6 |

37.69 % |

|

Latvia |

7 079 |

884.9 |

62.5 |

7.8 |

0.88 % |

|

Lithuania |

5 072 |

634.0 |

2.5 |

0.3 |

0.05 % |

|

Macedonia |

1 999 |

249.9 |

33.8 |

4.2 |

1.69 % |

|

Montenegro |

1 421 |

177.6 |

112.5 |

14.1 |

7.92 % |

|

Poland |

48 904 |

6 113.0 |

917.5 |

114.7 |

1.88 % |

|

Romania |

28 396 |

3 549.5 |

2 012.5 |

251.6 |

7.09 % |

|

Serbia |

21 665 |

2 708.1 |

3 306.3 |

413.3 |

15.26 % |

|

Slovakia |

9 422 |

1 177.8 |

163.8 |

20.5 |

1.74 % |

|

Slovenia |

7 468 |

933.5 |

411.3 |

51.4 |

5.51 % |

| 16+1 Initiative countries | 204 494 | 25 561.8 | 10 785.0 | 1 348.1 | 5.27 % |

Source: Macrotrends, Euro Dollar Exchange Rate (EUR USD) – Historical Chart, https://www.macrotrends.net/2548/euro-dollar-exchange-rate-historical-chart [accessed: 05.10.2023]; T. Matura, Chinese Investment in Central and Eastern Europe: A reality check. Budapest 2021, p. 14; UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2020: International Production Beyond the Pandemic, New York 2020, pp. 260-263.

This has therefore become the start of a discussion on the region’s cyber security, given China’s growing influence in 5G network technology, control of data flows due to Huawei’s cooperation with many telecom providers and the resulting concerns about spying[36].

In the context of the China’s current trade relations with CEE countries, it is worth referring to the value of trade between China and members of the TSI (table 2). Again, as with the FDI, the most important striking finding is the unequal distribution of benefits. The value of total exports of TSI countries to China is less than 20% of the total value of TSI countries’ imports from China. Associated with this inequality is the composition of trade between countries in question. While about 50% of Chinese exports to TSI countries are machines and electronics, some of the TSI countries serve mostly as a Chinese resource repository – for instance, in 2021 mineral products were responsible for over 60% of Greek exports to China, copper articles represented 49% of Bulgarian exports to China, whereas wood accounted for almost 40% of all Latvian exports to China[37]. While not being a part of the TSI, some Western Balkan nations have also voiced concerns about this issue – with Albania focusing on exporting chromium ore (38% of all exports to China), Macedonia on ferroalloys (65%) and Serbia on iron ore (48%)[38]. This has been an issue raised by the European Parliament for several years now, suggesting that the 16+1 format mainly serves as a platform for China to gain greater access to the European market while failing to offer a reciprocity in market openness.[39]

Thus, for none of the TSI countries is China a key importer – as with the exception of Bulgaria, for none of the individual countries does the share of exports to China exceed 3% of the value of their total exports, and for the region as a whole the figure is 1.79%. China represents a relatively more important role as a supplier to TSI countries – catering for 8.68% of the region’s total imports. Poland (USD 45.8 billion, including 51% of machines and electronics) and Czechia (USD 20.9 billion, including 72% of machines and electronics) are responsible for more than half the value of TSI countries’ imports from China. Therefore, in the event of a desire to achieve a greater degree of economic independence from China by seeking to establish closer relations with Taiwan, it can be concluded that the policies of Poland and Czechia will largely determine the shape of China’s further trade relations with the TSI countries[40].

Table 2: Value of trade between TSI countries and China in 2021

| Country | Total exports (bln $) | Exports to China (bln $) | Exports to China as % of total exports | Total imports (bln $) | Imports from China (bln $) | Imports from China as % of total imports |

| Austria | 198 | 5.91 | 2.98 % | 203 | 7.43 | 3.66 % |

| Bulgaria | 43.3 | 1.49 | 3.44 % | 45.8 | 2.56 | 5.59 % |

| Croatia | 22.8 | 0.323 | 1.42 % | 34.9 | 1.66 | 4.76 % |

| Czechia | 225 | 3.22 | 1.43 % | 198 | 20.9 | 10.56 % |

|

Estonia |

21.9 |

0.279 |

1.27 % |

26.2 |

1.55 |

5.92 % |

|

Greece |

82 |

1.23 |

1.50 % |

113 |

12.6 |

11.15 % |

|

Hungary |

137 |

2,63 |

1.92 % |

136 |

10.8 |

7.94 % |

|

Latvia |

20 |

0.218 |

1.09 % |

14.4 |

1.14 |

4.67 % |

|

Lithuania |

40.8 |

0.316 |

0.77 % |

42.7 |

2.16 |

5.06 % |

| Poland | 323 | 3.76 | 1.16 % | 354 | 45.8 | 12.94 % |

| Romania | 90.8 | 1.57 | 1.73 % | 111 | 6.89 | 6.21 % |

| Slovakia | 104 | 2.87 | 2.76 % | 101 | 5.6 | 5.54 % |

| Slovenia | 46.7 | 0,464 | 0.99 % | 57.1 | 6.59 | 11.54 % |

| TSI countries | 1 355.3 | 24.28 | 1.79 % | 1 447.1 | 125.68 | 8.68 % |

Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity database, https://oec.world/en [accessed: 05.10.2023].

4. Political circumstances

Unfortunately, geopolitical tensions found their vent during the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24th February 2022. Indeed, for strategic and ideological reasons, China and Russia have increasingly started to cooperate against Western countries, hence it can be assumed that Beijing was aware of the Russian invasion plans[41] – especially as the current situation provides a great opportunity for China to observe the mistakes of the Russian military, as well as the response of Western countries to aggression through economic sanctions and arms supplies[42]. This knowledge could, in turn, be applied in the future, given that, according to US intelligence, Xi Jinping has ordered the Chinese army to “achieve readiness to conduct an invasion of Taiwan in 2027”[43]. Nevertheless, this does not mean that such an invasion will actually take place – for the strong reaction of Western countries in the face of a war not far from the European Union’s eastern border took everyone by surprise, including Vladimir Putin, who expected a repeat of the situation after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, when the EU’s retaliation oscillated mainly in the diplomatic dimension[44]. This may therefore also lead Beijing to conclude that a possible invasion of Taiwan would not be a profitable venture. This is becoming increasingly likely in view of the firm stance of Western countries towards the war in Ukraine, as well as Chinese plans for the armed seizure of Taiwan. In August 2023, the total losses (including killed and injured troops) of the Russian army may already have reached 500,000 soldiers and a significant part of the military equipment it possessed at the beginning of the war[45], a multiple of the losses suffered by the Ukrainian side. Taking into account the fact that, according to official statistics, the Chinese army is significantly inferior to the Russian army in many aspects[46], this means that its potential to carry out a successful armed invasion of Taiwan is even smaller – something that Western countries, with the United States at the forefront, have begun to recognise.

In August 2022, US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi met with the Foreign Minister and the President of Taiwan, seeking to demonstrate her “unwavering commitment to supporting Taiwan’s thriving democracy”[47], which prompted an unusually fierce response from the Chinese side[48]. In response to these moves, President Joe Biden took a significant step away from the doctrine of strategic ambiguity that had been in place for more than 50 years, clearly declaring that the United States would defend Taiwan “if there is indeed an unprecedented attack” by directly engaging its military[49].

Japan, too, has in recent years begun to move away from the strategy of ambiguity it adopted over the post-war decades in a bid to avoid the rise of anti-Japanese nationalist movements in Chinese society[50]. In 2021, a high-ranking Japanese official referred to Taiwan in an official statement using the word ‘country’ for the first time, rather than ‘region’ as before, suggesting a significant change in the previous approach[51]. The views of late Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who had for years advocated stronger measures to guarantee Taiwan’s sovereignty, suggesting that “a Taiwan contingency is a contingency for Japan”[52], may also have been a significant turning point here. Thus, in late 2022, Japan’s new Prime Minister Fumio Kishida announced plans to raise defense spending to 2% of GDP by 2027[53]. The choice of date suggests that this is directly related to Xi Jinping’s order to “achieve readiness to invade Taiwan by 2027”, thus fulfilling a deterrent function against Chinese ambitions.

European Union member states have also begun to strengthen relations with Taiwan, calling it an “important partner and democratic ally in the Indo-Pacific” in 2021 and sending the first ever diplomatic delegation from the European Parliament[54]. However, this takes place in a broader diplomatic context – for the EU is currently trying to manoeuvre between expressing support for Taiwan’s independence and respecting the ‘One China’ policy, as maintaining positive relations with Beijing, and thus being able to exert political pressure on the Kremlin, may prove essential to ending the conflict in Ukraine[55]. Thus, although European countries have not expressed such clear-cut positions as the US or Japan, their growing support for Taiwan can be observed.

CEE countries in particular took a very negative view of China’s stance on the war in Ukraine. As mentioned earlier, the countries of the region had already for some time recognised the unequal distribution of benefits associated with cooperation with China (particularly in areas of FDIs and trade in goods), especially in the context of the EU’s economic recovery from the global financial crisis and the eurozone crisis, which originally became important arguments for establishing cooperation with China in 2012[56]. The first half of the 2010s was indeed a very productive period in the development of European-Chinese relations, given that the EU was looking to diversify its external relations after the economic crisis, while China sought new markets for the accumulated capital[57]. However, frustration and disillusionment with cooperation with China has been growing in CEE region since a few years already, especially in the context of Chinese political threats to countries which decided to prioritise relations with Taiwan, such as warning the Czech Senate president to “pay a heavy price” for his official visit to Taiwan in 2020[58], targeting Lithuania by economic sanctions for its decision to open the Taiwanese Representative Office[59], or spreading official Chinese propaganda through numerous Confucius Institutes[60]. Nevertheless, the Chinese position[61] relating to the war in Ukraine has become the most important turning point in relations with CEE countries, which began treating Beijing as an explicit threat.

This is because despite statements about their support for global peace, both China and Russia seem ready to attack or intimidate third parties, especially those smaller and militarily or economically weaker. While Moscow does it through direct military means, Beijing prefers to use indirect means of coercion to influence other countries’ behaviour[62]. Therefore, Taiwan’s and CEE countries’ experiences concerning their relations with bigger, assertive regional powers have contributed to the political rapprochement of CEE countries with Taiwan[63]. In 2022 Central European Institute of Asian Studies launched the Center for CEE-Taiwan Relations, which is “a specialized unit tasked with producing and disseminating expert knowledge necessary for ensuring sustainable development of relations between Taiwan and the EU, while having a special focus on the CEE countries”, and one of the pillars of its operations will be political relations and security[64]. In 2023 Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen has also established closer relations with the Czech President-Elect Petr Pavel, Lithuania’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Gabrielius Landsbergis and many representatives of Slovakia and Poland[65], which resulted in CEE countries becoming the key drivers in developing EU-Taiwan relations, making up 60% of all interactions between EU and Taiwan actors[66]. As a result of the political warming, an increasing number of Taiwan-backed venture capital firms are looking to expand their investments in Central and Eastern Europe and to act as a bridge for startups that want to grow their businesses in Asia and beyond – especially given that Taiwanese companies would also like to become involved in the reconstruction of Ukraine after the war[67].

All things considered, the recent proposals and moves taken by administrations of the Baltic states, Poland, Czechia, Slovakia and others regarding Russia and China signal a more proactive and confident foreign policy within the CEE countries and make it possible to presume that TSI members will increasingly place limits on China’s economic ambitions in the coming years[68].

5. Discussion on the prospects for TSI countries to maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan

As outlined throughout the chapter, on the international legal side there is no contraindication to establishing diplomatic relations with Taiwan. At the same time, current economic conditions allow for different conclusions and policy responses than was the case even a decade ago. In light of the information cited so far, it can therefore be concluded that the question of maintaining diplomatic relations with Taiwan now largely depends on political arrangements. A decision in this regard should therefore be tailored to the agenda and objectives of each country (or group of countries) that is considering establishing unofficial or official relations with Taiwan. Given the author’s Western affiliation, however, this section will be devoted to making recommendations of a political nature for TSI countries, taking into account the considerations made so far.

The first and most relevant issue with which to begin this review is, of course, the need to avoid armed conflict. Until recently, the possibility of a US-China conflict was very remote and unlikely, but since 2000, when the People’s Republic of China launched an extensive lobbying campaign to increase support for the ‘One China’ principle on the international stage, tensions over Taiwan’s status have been steadily rising. Today, therefore, the theme of minimising the risk of war between the world’s two most powerful powers is on the US military’s agenda[69]. Nevertheless, as can be seen from the example of the United States and Japan, they are simultaneously adopting a strategy of raising their military capabilities to a level that allows them to effectively deter aggressors, which is one of the main reasons why this situation is being referred to by some analysts as a ‘second Cold War’[70]. However, as neither side wants to create a situation in which China might feel provoked to invade, these actions are purely defensive in nature. Therefore, increasing own defense capabilities, with equipment that can be easily transferred to Taiwan’s defenders in the event of a conflict, seems to be the optimal solution in the current situation. A similar response can be expected from TSI countries, given the record defense spending planned for the coming years by many of the countries, with Poland in the lead[71].

Secondly, it is also worth mentioning the strategy of reducing the degree of economic dependence on China and thus limiting its ability to exert political pressure. As could be observed in Figure 3, China has over the last decades become an extremely important economy for global value chains, particularly in the export of parts, components and intermediates. This has enabled them to spread their growing sphere of influence among developing and emerging economies, greatly expanding the circle of countries expressing support for the ‘One China’ policy. The New Silk Road project, which has been under way for several years, despite its potential to support the economic development of the countries that comprise it, will also mean a significant increase in their degree of interconnectedness with China. Therefore, countries that wish to retain their decision-making power to maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan should consider gradually reducing the degree of their economic dependence on China.

The same conclusion has been reached by European Union member states, which aim to achieve a 20% share of global semiconductor production by 2030[72], in response to Europe’s declining resilience to supply disruptions in recent decades, due to the geographical concentration of supply chains in many industries. The situation is similar for TSI countries, which have been the target of Chinese political propaganda since a decade, escalating in recent years to the level of economic and political threats. However, as shown in Tables 1 and 2, the CEE and TSI countries are not economically dependent on China, unlike many developing countries in the New Silk Road initiative. This leaves them more room for maneuver when shaping relations with Beijing, implying freedom of choice regarding the establishment of diplomatic relations with Taiwan. Nevertheless, it should be borne in mind that the full regionalisation of the global economy, which may follow the adoption of a strict position by CEE countries toward Taiwan, may pose a significant risk of increasing tensions between emerging blocs[73], hence a complete cessation of economic cooperation with China would be highly undesirable. Instead, consideration should be given to gradual independence in key sectors of the economy[74].

A further, third issue relates to the diplomatic sphere and possible activities within the United Nations and other international organisations. In the context of the aforementioned arguments, it will be legitimate to question Beijing’s interpretation of Resolution 2758 currently being pushed, which only sought to address China’s dual representation in the General Assembly, whereas it did not in any way deny Taiwan’s right to self-determination.

However, it will not be necessary to deny the ‘One China’ policy – for it is sufficient to make the caveat that it is fully acceptable with regard to the unquestioned right of the Chinese Communist Party to rule China, ultimately resolving the problem of dual representation. However, it is not the same as exercising sovereignty over Taiwan, which under international law fulfils the prerequisites for being recognised as a state and thus has the right to self-determination. Democratic countries should therefore press UN-related organisations as well as others (such as the International Organisation for Standardisation; ISO) to reverse their decisions to use wording indicating China’s sovereignty over Taiwan, in particular ‘Taiwan, a province of China‘[75]. TSI countries could also develop a position towards Taiwan similar to the rationale of the U.S. Taiwan Relations Act, which makes Taiwan be treated the same as other countries, allows for supplying of necessary defense services and recognises it as a de facto foreign state – despite the lack of official diplomatic relations[76]. Poland might play a key role in this regard, given its position among TSI countries, and its hitherto highly restrictive One-China policy among the government’s efforts to avoid antagonizing Beijing[77].

The above recommendations touch on three main spheres of activity – diplomatic, economic and military – that can be used by TSI countries wishing to demonstrate support for Taiwan in its long struggle for international subjectivity, in view of the changes taking place in the international arena. However, these do not constitute a closed catalogue, and are only intended to highlight the most important issues in light of the considerations raised in this article. It should be borne in mind that, despite the need for each state to meet its own political objectives, in the case of Taiwan, the final decision as to how to shape diplomatic relations with the rest of the actors should rest with the Taiwanese themselves. Indeed, it can be argued that the current situation represents, in a sense, an optimal status quo to which they have managed to get used to and adapt[78], so that they do not run the risk of Chinese invasion – and, overall, the lack of international recognition is no longer a significant obstacle for them to establish informal relations with the other actors[79].

6. Conclusion

Taiwan’s current status has been shaped by a multitude of historical, legal, economic and political circumstances. As outlined throughout this article, the ‘one China’ principle promoted by the People’s Republic of China, according to which it should be treated as a Chinese province, lacks establishment in international law. As a result of post-war oversights and the actual intentions of the UN General Assembly when enacting Resolution 2758, Taiwan’s status remains unsettled, hence the question of interpreting the possibility of diplomatic relations with it is still open. At the same time, the rationale for treating it as a sovereign state under international law can be enumerated by referring, inter alia, to the principle of self-determination of peoples and the requirements for treating an entity as a state in terms of the Montevideo Convention.

Current economic conditions also allow for different conclusions and policy responses than was the case even a decade ago, referring back to the theory of institutional economics raised in the introduction. It can therefore be concluded that the question of maintaining diplomatic relations with Taiwan now largely depends on political arrangements, and the decision in this regard should therefore be tailored to the agenda and objectives of each country (or group of countries, such as TSI) that is considering establishing such relations. Over the past few years, for example, one could observe a slow shift in stance in this regard from the United States, Japan and EU member states, which, in the face of the war in Ukraine and rising tensions between Western countries and China, have begun to express support for Taiwan’s democratic society with greater boldness. Also, the TSI countries, due to their growing dissatisfaction with the course of cooperation with China and especially in view of the Chinese position on the war in Ukraine should – and most likely will – revise their policies toward China in the coming years. However, it is important to remember, in expressing support for Taiwan, to oscillate within a range of actions that will not carry the risk of armed conflict between Western countries and China – examples of which were discussed earlier.

Bibliography

-

P. Tůma, What’s driving Central and Eastern Europe’s growing ties with Taiwan?, “Atlantic Council”, 27.06.2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/whats-driving-central-and-eastern-europes-growing-ties-with-taiwan/ [accessed: 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

The Three Seas Initiative was established in 2015 and was initiated by the governments of Poland and Croatia. Its original premise was to strengthen regional cooperation and promote economic development. However, since the outbreak of war in Ukraine on 24 February 2022, its objectives were extended into the geopolitical dimension, through “promoting the European Union’s cohesion and reinforcing the transatlantic bond”, see Three Seas, Three Seas Initiative: Objectives, https://3seas.eu/about/objectives [accessed: 05.10.2023]. ↑

-

Which in turn are formed on the basis of beliefs and ideas, see D.C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. St Louis 1990, pp. 131-140. ↑

-

Thoroughly addressed in H. Kissinger, World Order. London 2015. ↑

-

A full overview of these is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the retreat of the Republic of China authorities to Taiwan in 1949 after losing a civil war to People’s Republic of China in 1945-1949 can be considered the most important point of reference, see K.T. Li, What Is Taiwan’s Legal Status According to International Law, Japan, and the US?, “The News Lens”, 02.12.2019, https://international.thenewslens.com/feature/taiwan-for-sale-2020/128242 [accessed 14.03.2023]. ↑

-

S. Winkler, Taiwan’s UN Dilemma: To Be or Not To Be, “Brookings Institute Taiwan-US Quarterly Analysis”. 20.06.2012, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/taiwans-un-dilemma-to-be-or-not-to-be/ [accessed 02.03.2023]. ↑

-

“The General Assembly […] Decides to restore all its rights to the People’s Republic of China and to recognize the representatives of its Government as the only legitimate representatives of China to the United Nations, and to expel forthwith the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek from the place which they unlawfully occupy at the United Nations and in all the organizations related to it.”, see United Nations, UN Resolution 2758: Restoration of the lawful rights of the People’s Republic of China in the United Nations. New York 1971. ↑

-

E.C. Economy, The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State. Oxford 2018, pp. 102-104. ↑

-

These are: Belize, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nauru, Palau, Paraguay, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Tuvalu, the Vatican and the Marshall Islands, see World Population Review, op.cit. ↑

-

Hereinafter, the Republic of China will be referred to as Taiwan, given its weakening relationship with the historic Republic, and due to the nomenclature which is commonly used nowadays. ↑

-

Wikipedia, Foreign relations of Taiwan, “Wikipedia”, 23.02.2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foreign_relations_of_Taiwan [dostęp: 07.03.2023]. ↑

-

It is ahead of countries such as Sweden (104 delegations), Norway (99 delegations) or Finland (85 delegations), among others, see G. Van der Wees, Is Taiwan’s International Space Expanding or Contracting?, “The Diplomat”, 14.12.2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/12/is-taiwans-international-space-expanding-or-contracting/ [accessed 02.03.2023]. ↑

-

International Conference of American States, Convention on Rights and Duties of States (inter-American), 26.12.1933, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/intam03.asp [accessed 06.03.2023]. ↑

-

In many cases, they are funded by the government, disseminating its official views and demands – meaning that they de facto perform similar tasks to embassies, see A. Pascal, Taiwan’s Think Tanks and the Practice of Unofficial Diplomacy, “The Asia Dialogue”, 20.08.2019, https://theasiadialogue.com/2019/08/20/taiwans-think-tanks-and-the-practice-of-unofficial-diplomacy/ [accessed 06.03.2023]. ↑

-

United Nations, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. New York 1966. ↑

-

Ibidem. ↑

-

Election Study Center, National Chengchi University. Taiwanese / Chinese Identity(1992/06~2022/12), https://esc.nccu.edu.tw/PageDoc/Detail?fid=7800&id=6961 [accessed 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

United Nations Treaty Collection, Status of Treaties: International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-4&chapter=4&clang=_en [accessed 06.03.2023]. ↑

-

More extensively addressed in J. Drun, B.S. Glaser, The Distortion of UN Resolution 2758 to Limit Taiwan’s Access to the United Nations. Washington, DC 2022, pp. 36-44. ↑

-

Y.J. Chen, Must Taiwan Remain Invisible for the Next 50 Years?, “The Diplomat”, 25.10.2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/10/must-taiwan-remain-invisible-for-the-next-50-years/ [accessed 06.03.2023]. ↑

-

United Nations, United Nations Charter. San Francisco 1945. ↑

-

Taiwan has the world’s 57th largest population – meaning that nearly 140 countries with populations smaller than Taiwan are represented at the UN, see Worldometer. Countries in the world by population (2023), https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-country/ [accessed 07.03.2023]. ↑

-

L. Chung, Support grows for Taiwan to take part in UN, but status change ‘still runs through Beijing’, ‘South China Morning Post’, 30.10.2021. ↑

-

A. Nicita, C. Razo, China: The rise of a trade titan, “UNCTAD News”, 27.04.2021, https://unctad.org/news/china-rise-trade-titan [accessed 07.03.2023]. ↑

-

Also, the New Silk Road initiative announced in 2013 by Xi Jinping is seen by many analysts in this context as a long-term strategy to economically link its neighbours with China, see Organisation of Economic Co-Operation and Development. The Belt and Road Initiative in the global trade, investment and finance landscape. Paris 2018, p. 4. ↑

-

C. Miller, Chip War. The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology. London 2022, pp. 163-167. ↑

-

Ibidem, pp. 164-165. ↑

-

BBC, A quick guide to the US-China trade war, “BBC News”, 16.01.2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-45899310 [accessed 09.03.2023]. ↑

-

R. Richard, China and the race for technological supremacy, “Polytechnique insights”, 23.03.2022, https://www.polytechnique-insights.com/en/braincamps/economy/the-technology-war-between-china-and-the-usa/china-and-the-race-for-technological-supremacy/ [accessed: 05.10.2023]. ↑

-

M. Maciejewska, Inicjatywa Trójmorza vs Inicjatywa Pasu i Szlaka,”Układ Sił” 2022, no. 36, pp. 93-97. ↑

-

E. Ricci, The 16+1 Initiative, “Geopolitica.info”, 21.02.2019, https://www.geopolitica.info/the-161-initiative/ [accessed: 05.10.2023]. ↑

-

However, growing tensions between China and Western countries due to their failure to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine have provided a pretext for some of the countries to review the rationale for belonging to the Chinese initiative. Lithuania has left the format in 2021, while Latvia and Estonia have left in 2022, see D. Kochis, Europe Must Put China’s 16+1 Format Out of Its Misery, “The Heritage Foundation”, 10.08.2022, https://www.heritage.org/asia/commentary/europe-must-put-chinas-161-format-out-its-misery [accessed: 05.10.2023]. ↑

-

B. Kowalski, All quiet on the Eastern front: Chinese investments in Central Europe are still marginal, “Central European Institute of Asian Studies”, 18.06.2019, https://ceias.eu/all-quiet-on-the-eastern-front-chinese-investments-in-central-europe-are-still-marginal/ [accessed: 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

A. McCaleb, Á. Szunomár, Chinese foreign direct investment in central and eastern Europe: an institutional perspective, (in:) Chinese investment in Europe: corporate strategies and labour relations, Drahokoupi J. (ed.). Brussels 2017, p. 129. ↑

-

G. Lewicki, China’s Belt and Road meets the Three Seas Initiative Chinese and US sticky power in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and Poland’s strategic interests. Warsaw: 2020, pp. 26-28. ↑

-

Ibidem. ↑

-

See Observatory of Economic Complexity database, https://oec.world/en [accessed: 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

Ibidem. ↑

-

See G. Grieger, E. Claros, China, the 16+1 format and the EU. Brussels: 2018. ↑

-

It is worth adding here that following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine and the deterioration of China’s relations with Western countries, which will be discussed in more detail in the next section, the value of trade with China has most likely decreased – however, this has not yet been reflected in the text due to the lack of availability of the most recent data. ↑

-

On 4th February 2022 China and Russia declared their “boundless friendship”, which, according to many commentators, became the reason for the official confirmation of the Beijing-Moscow axis, see S. Czubkowska, op.cit., p. 82. ↑

-

C.Y. Lee, Ukraine and Taiwan: Comparison, Interaction, and Demonstration, “Taiwan Insight”, 04.04.2022, https://taiwaninsight.org/2022/04/04/ukraine-and-taiwan-comparison-interaction-and-demonstration/ [accessed 09.03.2023]. ↑

-

M. Martina, D. Brunnstrom, CIA chief warns against underestimating Xi’s ambitions toward Taiwan, “Reuters”, 03.02.2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/cia-chief-says-chinas-xi-little-sobered-by-ukraine-war-2023-02-02/ [accessed 09.03.2023]. ↑

-

N.N. Taleb, A Clash of Two Systems, “Incerto”, 19.04.2022, https://medium.com/incerto/a-clash-of-two-systems-47009e9715e2 [accessed 09.03.2023]. ↑

-

H. Cooper, T. Gibbons-Neff, E. Schmidt, J.E. Barnes, Troop Deaths and Injuries in Ukraine War Near 500,000, U.S. Officials Say, “The New York Times”, 18.08.2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/18/us/politics/ukraine-russia-war-casualties.html [accessed: 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

In particular, in terms of military equipment owned, see Global Firepower, Comparison of China and Russia Military Strengths (2023), https://www.globalfirepower.com/countries-comparison-detail.php?country1=china&country2=russia [accessed 06.20.2023]. ↑

-

H. Davidson, Nancy Pelosi arrives in Taiwan as China puts military on high alert, The Guardian, 02.08.2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/aug/02/nancy-pelosi-lands-in-taiwan-amid-soaring-tensions-with-china [accessed 13.03.2023]. ↑

-

Ibid. ↑

-

Rzeczpospolita. Biden: Jeśli Chiny zaatakują Tajwan, będziemy bronić wyspy. “Rzeczpospolita”, 19.09.2022, https://www.rp.pl/dyplomacja/art37078011-biden-jesli-chiny-zaatakuja-tajwan-bedziemy-bronic-wyspy [accessed: 07.03.2023]. ↑

-

Y.H. Chen, Japan’s Taiwan Policy in the Xi Jinping Era: Moving Toward Strategic Clarity. “Strategic Review” 2022, no. 15, pp. 299-302. ↑

-

Ibid. ↑

-

K. Takahashi, How Would Japan Respond to a Taiwan Contingency?, “The Diplomat”, 20.08.2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/how-would-japan-respond-to-a-taiwan-contingency/ [accessed 13.03.2023]. ↑

-

T. Kajimoto, T. Yamaguchi, Japan unveils record budget in boost to military spending, “Reuters”, 23.12.2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/japan-unveils-record-budget-boost-military-capacity-2022-12-23/ [accessed 13.03.2023]. ↑

-

A. Qin, S. Erlanger, As Distrust of China Grows, Europe May Inch Closer to Taiwan, “The New York Times”, 10.11.2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/10/world/asia/taiwan-europe-china.html [accessed 13.03.2023]. ↑

-

Interestingly, according to the European Union’s current position, ‘the One China Policy does not prevent us – the European Union – from continuing and intensifying our cooperation with Taiwan’, suggesting that Taiwan is treated by the European Union as an entity entirely separate from China, in line with the interpretation presented in the previous sections, see M. Esteban, M. Malinconi, EU-Taiwan relations continue to expand in the framework of the One China Policy, “Elcano Royal Institute”, 10.10.2022, https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/commentaries/eu-taiwan-relations-continue-to-expand-in-the-framework-of-the-one-china-policy/ [accessed 13.03.2023]. ↑

-

R.Q. Turcsányi, China and the Frustrated Region: Central and Eastern Europe’s Repeating Troubles with Great Powers, “China Report” 2020, no. 56, pp. 60-77. ↑

-

J. Melnikova, China and Europe: What Was It? The Rise and Crumbling of the ‘16+1’ Format, “Valdai Discussion Club”, 26.01.2023, https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/china-and-europe-what-was-it-the-rise-and-crumblin/ [accessed: 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

I. Karásková, A Foreign Policy Pendulum: Explaining the Tension between Normative Impulses and Economic Interests in Czech-China Relations, “Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung”, 20.10.2020, https://cz.boell.org/en/2020/10/20/foreign-policy-pendulum-explaining-tension-between-normative-impulses-and-economic [accessed: 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

Deutsche Welle, Taiwan opens representative office in Lithuania, “Deutsche Welle”, 18.11.2021, https://www.dw.com/en/taiwan-opens-representative-office-in-lithuania/a-59853874 [accessed: 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

Thoroughly addressed in S. Czubkowska, Chińczycy trzymają nas mocno. Kraków 2022. ↑

-

Including decision to back Russia’s claims on redesign of European security architecture through a joint statement opposing the enlargement of NATO on 4th February 2022, see Russian Federation, People’s Republic of China. Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development. Beijing 2022. ↑

-

For instance, Taipei keeps living under constant pressure from Beijing, including growing numbers of incursions into Taiwanese air defense identification zone by Chinese warplanes or disinformation campaigns, see R. Kumar, In Taiwan China has launched a disinformation campaign in Chinese on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, “Reuters Institute”, 29.03.2022, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/news/taiwan-china-has-launched-disinformation-campaign-chinese-russian-invasion-ukraine [accessed: 07.10.2023]. ↑

-

A. Bachulska, Taiwan and Central and Eastern Europe Are More Than Just Pawns in Bigger Players’ Game, “China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe”, 06.10.2022, https://chinaobservers.eu/taiwan-and-central-eastern-europe-are-more-than-just-pawns-in-bigger-players-game%EF%BF%BC/ [accessed: 07.10.2023]. ↑

-

M. Šimalčík, CEIAS launches Center for CEE-Taiwan Relations, “Central European Institute of Asian Studies”, 28.04.2022, https://ceias.eu/launching-center-for-cee-taiwan-relations-2/ [accessed: 07.10.2023]. ↑

-

C. Horton, China is losing Europe’s east to Taiwan, “The China Project”, 31.01.2023, https://thechinaproject.com/2023/01/31/china-is-losing-europes-east-to-taiwan/ [accessed: 07.10.2023]. ↑

-

M. Hudec, Central Europe drives EU-Taiwan relations, “Euractiv”, 14.03.2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/central-europe-drives-eu-taiwan-relations/ [accessed: 07.10.2023]. ↑

-

R. Bartlett-Imadegawa, Taiwan-backed fund invests in Central, Eastern Europe as ties warm, “Nikkei Asia”, 24.06.2023, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Taiwan-backed-fund-invests-in-Central-Eastern-Europe-as-ties-warm2 [accessed: 07.10.2023]. ↑

-

I. Karásková, How China lost Central and Eastern Europe, “Mercator Institute for China Studies”, 22.04.2022, https://www.merics.org/en/comment/how-china-lost-central-and-eastern-europe [accessed: 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

N.K. Cobbins, Taiwanese Sovereignty & the United States’ Assurance and Dissuasion Alliance to Combat Chinese Use of Force, July 2021, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ISR/student-papers/AY21-22/TaiwaineseSovereigntyDissuation_Cobbins.pdf [accessed 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

G. Rachman, Ukraine and the start of a second cold war, “Financial Times”, 06.06.2022, https://www.ft.com/content/34481fbd-4ca7-4bb3-bef5-e68fefed7438 [accessed 13.03.2023]. ↑

-

Poland has increased its minimum statutory requirement of military spending to 3% of GDP, starting from 2023, see J. Ciślak, Polska planuje gigantyczne wydatki na obronność w 2023 roku, “Defence24”, 30.08.2022, https://defence24.pl/polityka-obronna/polska-planuje-gigantyczne-wydatki-na-obronnosc-w-2023-roku [accessed: 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

Kearney. Europe’s urgent need to invest in a leading-edge semiconductor ecosystem. Atlanta 2021, p. 24. ↑

-

M. Ruta, How the war in Ukraine is reshaping world trade and investment, “World Bank Blogs”, 03.05.2022, https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/how-war-ukraine-reshaping-world-trade-and-investment [accessed 14.03.2023]. ↑

-

These will vary depending on the degree and development strategy of the economy concerned. For example, for highly developed countries such a key sector may be semiconductors, while for developing countries it may be heavy industry or energy. ↑

-

J. Drun, B.S. Glaser, op.cit, p. 6. ↑

-

According to its contents, Taiwan shall be “treated under U.S. laws the same as foreign countries, nations, states, governments, or similar entities”, thus recognising it as the equivalent of a foreign state. It also stipulates that “the United States will make available to Taiwan such defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability”, see United States Congress, Taiwan Relations Act: H.R. 2479. Washington 1979. ↑

-

M. Šimalčík, A. Gerstl, D. Remžová, Beyond the Dumpling Alliance: Tracking Taiwan’s relations with Central and Eastern Europe, Bratislava 2023, pp. 98-111. ↑

-

According to Election Study Center of National Chengchi University, when it comes to Taiwanese declared preferences for Taiwan’s status quo, the two most popular responses representing the combined views of nearly 60% of the public advocate maintaining the status quo for as long as possible, while all variants oscillating around maintaining the status quo at least some of the time is a view shared by more than 75% of Taiwanese in total, see Election Study Center, National Chengchi University, Taiwan Independence vs. Unification with the Mainland(1994/12~2022/12), https://esc.nccu.edu.tw/PageDoc/Detail?fid=7801&id=6963 [accessed: 06.10.2023]. ↑

-

T.S. Rich, Does It Matter If Taiwan Loses Formal Recognition?, “Australian Outlook”, 19.10.2019, https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/does-it-matter-if-taiwan-loses-formal-recognition/ [accessed 06.10.2023]. ↑