The author : Adalgisa Martinelli graduates in International Affairs at University of Bologna in December 2022, with a Master thesis on “The role of agriculture between Africa and EU relations: Kenya case-study” supervised by Professor Arrigo Pallotti. On May 2023, she receives the award America Giovani from Fondazione Italia-USA for talent and curriculum. Her goal is to research on the role of small farmers in East Africa, applying Elinor Ostrom’s theory and shed light on the current food sovereignty challenge.

Blue Europe is an indipendent think tank and does not approve nor share the content or the position of invited authors. The article was created during the 2022 Blue Europe student contest.

Introduction

The Kosovo conflict is the predictable consequence of the long-term shadow of the manipulation of history and the so-called “interethnic conflicts”. The area represents a perfect example of a conflict-ridden and segregated society in which two different cultures live completely separated in parallel societies (Strapcova, 2016: 56–76).

The research question aims to understand the local role in Kosovo after the conflict in re-building their society; we will focus only in one field: the education system. The essay will show in detail that multiculturalism led to an ethnic-based education system; nonetheless, education reflects the tension between exclusivist nationalistic concerns and multicultural international models. The international focus on stability and Serbo-Albanian nationalistic competitive agendas have led to an education that reflects and reproduces this conflict.

International mission – UNMIK

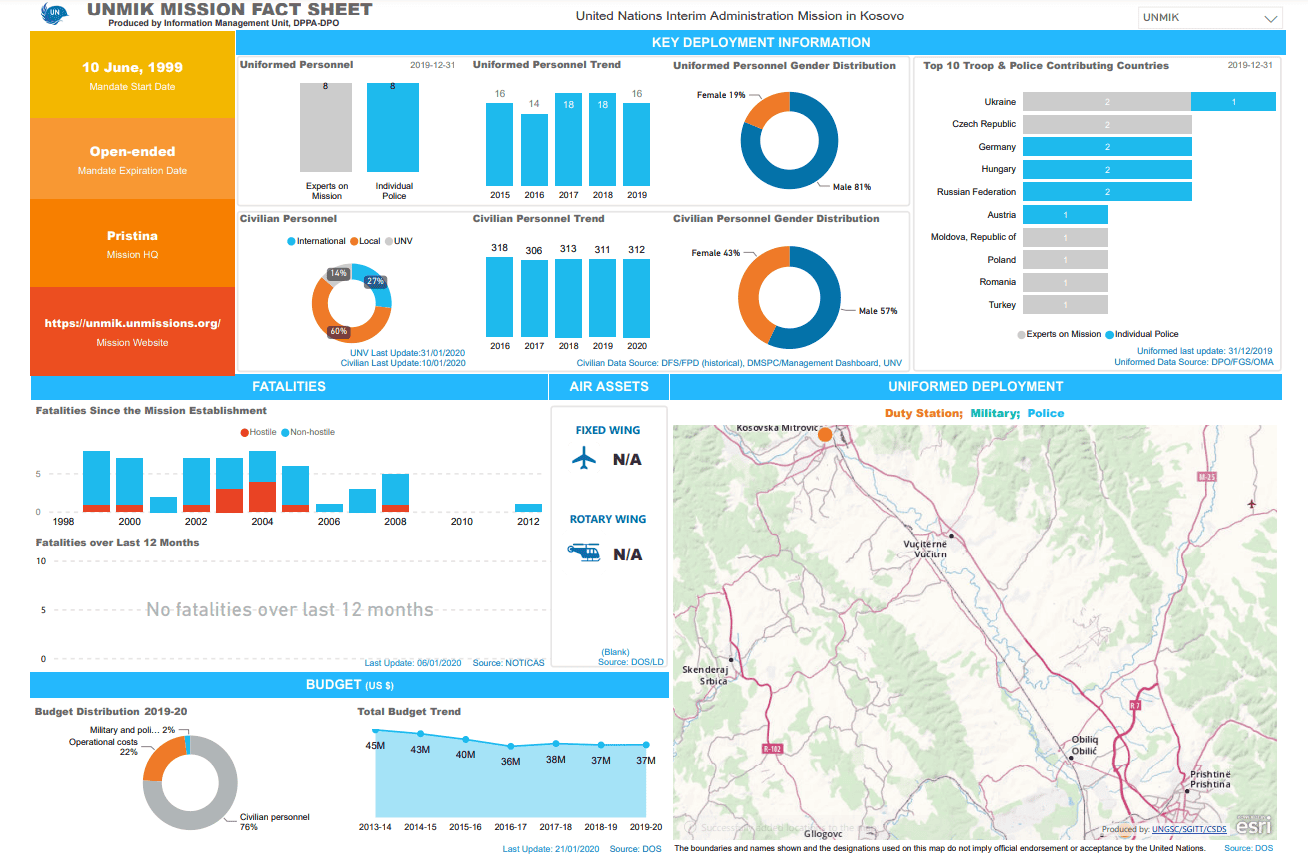

On 10th June 1999, the mandate of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) is established by the Security Council in its resolution 1244. Having its headquarters in Pristina, the goal is helping to ensure conditions for a peaceful and normal life for all inhabitants of Kosovo and advance regional stability in the Western Balkans area (UNMIK, w.p., online). The task of letting people in Kosovo enjoy a substantial autonomy, highlights the unprecedent and complicate scope of the UN mission (Mandate UNMIK, 2016, w.p., online). The Security Council vested UNMIK of all power: legislative, executive and administration of justice. In 1999 the UN establishes also an international military force with NATO’s leadership. KFOR is a NATO-led international military mission initially established with a broad mandate: to avoid clashes and threats against Kosovo by Serbian and Yugoslav forces; to re-establish and maintain public security and civil order in the region; demilitarize the UÇK (Albanian name of the Kosovo Liberation Army); support humanitarian efforts; support the international civilian presence and act in coordination with it (ISPI, 2009, w.p., online: 1).

In the resolution 1244, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) is included under the status of UNMIK’s pillar for institution building (UNMIK, w.p., online). In addition, the Special Representative also ensures coordination with the head of the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX), operating under the United Nation’s authority, which has operational responsibility in rule of law. The UN Office in Belgrade represents the political and diplomatic role and liaises with the political leadership of Serbia (UNMIK, w.p., online).

In the resolution 1244, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) is included under the status of UNMIK’s pillar for institution building (UNMIK, w.p., online). In addition, the Special Representative also ensures coordination with the head of the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX), operating under the United Nation’s authority, which has operational responsibility in rule of law. The UN Office in Belgrade represents the political and diplomatic role and liaises with the political leadership of Serbia (UNMIK, w.p., online).

Despite the Unilateral Declaration of Independence of Kosovo on the 17 February 2008 (It has been recognized by more than 100 UN Member States), UNMIK continues to operate in this area under its mandate of 1999 with the status of neutral manner (UNMIK, w.p., online). However, the priorities of the Mission are changed; promoting security, stability, and respect for human rights in Kosovo and in the region are at stake (Mandate UNMIK, 2016, w.p., online). 2013 is a crucial year, in fact on 19th April is approved the “First Agreement of Principles Governing the Normalization of Relations” and there is a more collaborative dialogue with the European Union, trying to achieve a more structural progress in the Westernization of local institutions. UNMIK’s originally heavily presence, has been redesigned to a sort of day-to-day functions in favour of EULEX which itself operates within the framework of Security Council Resolution 1244 institutions (Mandate UNMIK, 2016, w.p., online). On 29 January 2009, following the termination of the operational activity of the UNMIK Mission, the national staff, employed, returns in its own homeland. However, the mission headquarters remained open for reasons of political expediency, linked to the official recognition of EULEX (Generalità – Difesa,w.p., online).

UNMIK is a unique mission of its kind, managing the activities of other non-UN organizations under full UN jurisdiction. The mission is essentially composed of four components (so-called Pillars):

- Pillar I: humanitarian assistance (under the leadership of UNHCR, the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees). The UNCHR provides humanitarian aid and facilitating the return of refugees and displaced persons. With the return of most of the refugees, Pillar I end in June 2000. However, the problem is not completely solved and the UNCHR still continues to work under disguised forms (Şafak, 2016: 106).

- Pillar II: civil administration (under the leadership of the United Nations). Regarding Pillar II, the civil administration of Kosovo is directly controlled by the UN mission. In 2005, this pillar is almost completely deployed to local authorities taking over most of the civil administration functions (Şafak, 2016: 106).

- Pillar III: development of democratic institutions (under the leadership of the OSCE, the Organization for Co-operation and Security in Europe). The OSCE is assigned Pillar III, “managing democratization and institution building”. The mission, which is among the largest OSCE field operations, runs a wide array of activities, from the development of democratic institutions and civic participation in decision-making to the promotion of human rights and the rule of law. The organization is particularly engaged in the protection of community rights; monitoring the judiciary; local governance reform; and the development of independent institutions, such as the Ombudsperson Institution of Kosovo, the Independent Media Commission, the Central Election Commission, the Kosovo Judicial Institute, and the Kosovo Police. This is the first time the organization has structurally linked this mission to a UN mission (Şafak, 2016: 106).

- Pillar IV: reconstruction and economic development (under the leadership of the European Union). Pillar IV, performed by the EU, who is the largest donor to Kosovo, and is headed by the Deputy SRSG for economic reconstruction, is characterized by activities focusing on economic reconstruction in the war-torn country (Şafak, 2016: 106). Martina Spernbauer defines EU activities as “peacebuilding” and states that EU assistance gradually shifted from reconstruction to institution-building and the rule of law (Spernbauer, 2014: 159).

The mission’s structure has the aims to promote the creation of democratic institutions in Kosovo and to set the stage for long-term solutions for economic and social reconstruction even during the phase of humanitarian assistance and emergency aid (Generalità – Difesa,w.p., online).

The declaration of independence by the Kosovo authorities requires an important change in the peace operation deployed (Şafak, 2016: 107). First, UNMIK tasks are downsizing and ceasing some of them to EULEX. Although the EU has been part of the UN Kosovo mission since the beginning, EULEX has been playing the main role for the peace operation in Kosovo on the EU’s behalf since 2008. EULEX is the largest civilian mission ever launched under the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP). The central aim of the mission is to assist and support the Kosovo authorities in the guarantee of the rule of law (Şafak, 2016: 107). After independence, the International Civilian Representative (ICR), also working as the EU Special Representative (EUSR), for Kosovo, becomes the main authority in Kosovo and encourages the implementation of the Ahtisaari Plan (2007). In September 2012 international supervision ends, and Kosovo became responsible for its governance (Şafak, 2016: 107).

Peacekeeping: the historical precedent

The international mission in Kosovo has been categorized in various ways. The UN classifies UNMIK mission as peacekeeping operation, defining it as “a technique designed to preserve the peace, however fragile, where fighting has been halted, and to assist in implementing agreements achieved by the peacemakers.” (UN, 2008: 18). The traditional term ‘peacekeeping’ had a generally accepted definition: a multinational force, sometimes with a civilian element, mandated to administer, monitor, or patrol in conflict areas in a neutral and impartial way, usually with the consent of the parties to a dispute, and nearly always under the provisions of Chapter VI of the UN Charter (Pugh, 2004: 11). UNMIK is part of the second generation of peacekeeping operations, with a completely new mandate focusing on the separation of forces.

NATO officials call their mission a “peace support operation”, stating on their official website that “NATO has been leading a peace-support operation in Kosovo since June 1999 in support of wider international efforts to build peace and stability in the area.” (NATO, w.p., online).

UNMIK is the precedent in the history of UN peacekeeping operations, because for the first time four international organizations operated under UN leadership, along with NATO’s involvement. For this reason, in international law theory there is no unique qualification for UNMIK; especially regarding the pillar system has been one of the most important characteristics of UNMIK.

John Cockell supports this idea and argues that UNMIK and KFOR have undoubtedly been the most successful but also complex Balkan operations, showing that many lessons are effectively applied in the international peace building response to the Kosovo conflict (Cockell, 2003: 113)

Tasking international organizations with civilian activities, assigning the UN as coordinator and leader of these organizations, and support civilian counterparts are few lessons learned from the Bosnian operation. The peacekeeping operation due to the difficulty of the mandate and the lack of political collaboration of the parties in the region, produces two negative externalities: confusion over the rule of engagement and inadequate resources and logistics. The above-mentioned outcomes are predictable if the reader considers that the UN faces three major issues:

- Transition towards what? Goal is ambiguous.

- Address the root causes of the conflict, aiming at preventing another escalation of violence. However, who can define what are the root causes of the conflict? The answer relies on the perspective chosen.

- Lack of coordination among the representative of the four pillars of the mission

Broadly speaking, the international efforts to promote peace and security in a post conflict country often clashes with the ambiguity of the goals. The above assumptions result in a lack of effectiveness in a conflict affected country (Choedon, 2010: 41-47).

Hybrid peace governance

Most of the time, the major challenge is to find a compromise between international actors and local population, because both claim the ownership of being in command. The result is usually a hybrid peace governance, where liberal and illiberal norms coexist; hybridity is an unplanned consequence resulting in a background where war and peace are blurred concepts. There are three categories that describe hybrid peace governance: victor’s peace, divided state, and anarchy. Kosovo is part of the first category, the most common: the truce established combines liberal and illiberal institutions. Formally, there are all the democratic elements (elections, for example) but the absence of war is not reached by a peaceful compromise but after the defection of the opposition by force (Jarstad & Belloni, 2012: 1-6).

Local role

International peace initiatives have become increasingly prominent; however, it is widely agreed that peace is only sustainable when it is driven and led locally, that is, by the people and institutions of the country or countries concerned. They know the context well enough to judge what measures might work, and have the knowledge, relationships and motivation needed to ensure they do work, especially over the longer term (Autesserre, 2017: 114).

Local peacebuilding is related to peacebuilding initiatives owned and led by people in their own context. It includes small-scale grassroots initiatives, as well as activities undertaken on a wider scale (Autesserre, 2017: 114). International organisations neglect local initiatives for three principal reasons:

- There is a strong aversion towards risks: international organisations often lack confidence that local organisations will implement programmes and steward resources effectively.

- Many international organisations find it operationally difficult to collaborate with local initiatives; there is a huge distance between local communities and international organizations due to limited knowledge and understanding of local context.

- There is a limited body of recognised evidence demonstrating the success of local initiatives, which makes it difficult to allocate resources to them. This is exacerbated by a prevalent understanding that ‘successful’ peacebuilding means having an impact on highly visible political or economic processes (Autesserre, 2017: 115).

When community-based peace initiatives are adopted as part of local governance mechanisms, their ongoing contribution is sustained, representing a structural change. Successful community-based peace structures tend to reflect the diversity of their communities, and allow people of different genders, ages, and ethnicity to have their issues heard. Local peacebuilders who engage specific segments of the community have clearly shown they can make a difference. By tailoring their initiatives to those whose experience of conflict has left them traumatised, to young people who so often become the tools of conflict entrepreneurs, and to women whose potential to contribute to peace has been overlooked, they have helped these groups begin to shape more peaceful societies.

“Local turn” is terra nullius and the requirement to establish peace again is used to justify the implementation of international actions. UN Security Council Resolution 2282 on Sustaining Peace mandates declares that the UN and its member states must implement and support peacebuilding initiatives at all stages of the conflict cycle, and ‘reaffirms the importance of national ownership and leadership in peacebuilding, whereby the responsibility for sustaining peace is broadly shared by the Government and all other national stakeholders and underlines the importance […] of inclusivity’ (UN, 2016, w.p., online). This statement is matched by other international policies, and by peacebuilding theory, which consistently state that local initiatives are essential for peace. While there is no shared policy benchmark for the minimum proportion of peacebuilding aid that should be given to local initiatives, nor accurate data about the proportion that is currently flowing to local initiatives, the Charter for Change – which calls for the ‘localisation’ of humanitarian aid – has set the initial benchmark at 20% of total humanitarian funding (Charter for change, w.p., online).

Local peacebuilders are making a substantial impact but need more support to expand and deepen their efforts. The UN should reform his approach towards local peacebuilding, following these requirements:

- Increase levels of sustained funding to local peacebuilding initiatives at all stages of the conflict cycle, in ways that respect their leadership and autonomy.

- Collaborate with and support local peacebuilders to help maximise their direct and indirect impact.

- Support local peacebuilders to generate and take advantage of learning about what works locally.

- Adapt the way donors, multi-lateral organisations, and international NGOs work, to make it easier to collaborate with and support local peacebuilders, and for local peacebuilders to access support (Autesserre, 2017: 128-129).

- Education system

Focusing on our research question: is there a link between education policies and liberal peace in post-conflict Kosovo?

Regarding the education field, the international community adopts a blank slate approach: ignoring every institutional inheritance survived and indifferent to the ownership and capacity of the locals to re-build their nation. Many critics define these approaches as neo-colonial, making a comparison with the French assimilation system in Africa during the ‘30. In such fragile contexts, education reform is normally regarded as a developmental activity, and thus as an integrated part of a wider process of rebuilding institutions and assisting the reconciliation process to achieve long-term stabilization and lasting peace. Indeed, the role of the international community in this sector is unprecedented, because our case-study is an emerging example of postintervention societies. Education is one of the core fields of intervention, because the international community knows the historical role played by the national question causing the war. Whoever would be in command of the education system will win the war because the winners can re-shape the history. Following these assumptions, the UN tries to spur multiculturalism and Westernization hoping to integrate Kosovo in the European Union and in the global market (Ervjola, 2018: 1-2).

Regarding the school system, does the hybrid peace governance established in Kosovo give voice only to international inputs and not take in consideration local agents’ efforts in shaping educational policies?

In Kosovo, foreign actors are essential to initiate this process, as previous attempts of implementing such policies made by the local population crashed in most cases. It is important to underline that local authorities work parallel to UNMIK, even if the UN mission maintains ‘exclusive’ power over crucial sectors: Kosovo’s economy and foreign policy; while the local authorities gain gradual ownership in ‘transitional areas’, such as education. The nexus between education, conflict and peace in post-war contexts has received growing attention in the past two decades.

During 1999-2001, the UN reforms the education system considering the report of Bush & Saltarelli (UNICEF) “The Two Faces of Education in Ethnic Conflicts”. In this report, the double role of education is analysed in a context where ethnicity is a highly politicized issue towards which the government is legitimate to go in war and the public opinion justifies this identity war. In the report, education can prevent and address the root causes of the conflict; however, at the same time, education can be manipulated and amplify discriminations as well as exacerbate the conflict by reproducing the structural inequalities and injustices (Bush & Saltarelli, 2000: w.p. online).

On 19 November 1969, the foundation of the University of Pristina in the Albanian language, is a symbol of autonomy after a lot of years of segregation. In 1974 after the Yugoslav constitutional reform, Kosovo has total control over governance of education and its contents. Now, Kosovo-Albanians can teach and learn about their own history. During the 1980s, Belgrade starts to regain control over the school system introducing separated buildings, more focus on Serbian history… This renewed centralization causes some riots around the University of Pristina in 1981. After 1990, the oppression culminates with the expulsion of teachers and the closure of secondary schools (Ervjola, 2018: 5).

Kosovo Albanians responds with the proclamation of the shadow ‘Republic of Kosovo’, a parallel system of governance. Kosovar pupils boycott classes and they attend parallel schools in homes, garages, cellars; the education system is ethnically segregated in structure and content. It is a typical form of non-violent strategy to protest and, during the 1990s, it plays a fundamental political role. However, the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords failure trigger new waves of student protests and the central government starts to believe that control over the shadow system is essential to show strength. After the war, UNMIK assumes full control in managing educational reconstruction (Ervjola, 2018: 5).

At the beginning, OSCE’s goal is to create a unified educational system, but also promote a pluralist approach representing all minorities of the society. Progressively, there is a transfer of competencies for education reform and governance to local authorities (completed in 2001). European standards and the importance of inclusiveness are the ultimate goals of UNMIK. The Kosovo Education Strategic Plan 2011–2016 is a crucial step towards a more comprehensive school system (Ervjola, 2018: 6).

Education for minority communities and their rights to access to education is still a massive problem. For this reason, UNMIK tries to implement as many inclusive policies as possible aiming at promoting equality between different ethnic groups. Even if some schools try to implement the above policies, the lack of will from the communities will bring failure to the program. By 2000, the parallel system of education comes back stronger than ever; as a matter of fact, a system for the recognition of Serbian curricula and textbooks that could be used by the Kosovo education system at the municipal level is not put in place. OSCE’s attention towards minorities is reflected in the institution of curricula in different languages; despite all the effort, in 2009 it is reported that curricula for community-specific ‘national’ subjects are not developed yet. Besides, the ones deployed are not promoting integration and inclusivity. In addition, Kosovo’s curriculum and textbooks have not been translated into Serbian, suggesting that Kosovo institutions are lacking both the will and the strategy for integrating the Serbian parallel education system into the education system of the new State (Ervjola, 2018: 6-8).

More controversial is the situation with higher education; in particular, universities are extremely politicized, and they become the place where the inter and intra-ethnic visions clash several times (many students were involved in the war). UNMIK try to transform the University of Pristina into a democratic, non-segregated institution; however, PISG does not accept Serbs applications, bringing failure to the international attempt. The University of Pristina is regarded as a tool to bring democratization into the country, but the international community understands that to establish a peaceful pattern it is necessary to link education and economy. Despite some efforts by the international community to offer scholarships for minorities in Kosovo, the university does not appeal to Kosovo Serbs. Given resistance from local actors, internationals’ vision for an inclusive and multi-ethnic university is gradually replaced with ethnically separate universities within the same system. It is only between 2000 and 2003 that the two universities of Pristina seem to develop in parallel; however, several political events such as the assassination of the Serbian Prime Minister in 2003, the resumption of a more nationalist government in Serbia, the violent March riots in Kosovo in 2004, and the unilateral declaration of independence break the initial attempt to collaborate. After UDI by Kosovo Albanian authorities, the UPKM is identified by the Serbian Government as the ‘forefront of the defence of Serb national interests’ and the university adopts the same Serbian official reaction to opposing Kosovo’s independence. The creation of the University of Prizren, including programs for teacher education in Bosnian, is a clear sign of resistance towards integration. Reforms and policy instruments developed upon the Bologna Process have the objective to transcend the ethnic nature of university and to be involved into a Westernization process. Still the segregation of two universities continues to symbolize separation between Kosovo Serb and Kosovo Albanian communities. Until the Declaration of Independence in 2008, local governments maintain a restrictive approach towards higher education (Ervjola, 2018: 9- 11).

In 2013, the European Council publishes a report shedding light on the corrupted system of education; the University of Pristina is in the spotlight regarding scandals for unfair promotions. Even if Kosovo’s scholars argue that the liberalization of education lowered its quality, the proliferation of private universities has political and not economic reasons behind. No matter the implementation of reforms based upon the Bologna Process, the University of Pristina does neither compare nor compete with universities in other European countries. The diplomas, knowledge, and skills produced do not match those demanded by the European market, increasing youth unemployment and general dissatisfaction in the country (Ervjola, 2018: 12- 14). The international attempt to link education and economy is failed; consequently, the threat of a latent conflict remains.

Conclusion

The rivalry between the superpowers did not allow the UN to provide a lasting or effective solution for interstate or intrastate conflicts during the Cold War. That rivalry resulted in the invention of “traditional” peacekeeping operations, which was foreseen neither in the UN Charter nor in other official documents. The peacekeeping operation became a feasible solution for the UN to fulfil its main responsibility while preventing conflicts from becoming major security problems involving the superpowers. Post-Cold War conflicts, with serious humanitarian crises, opened a new era in peacekeeping operations, requiring wider and more comprehensive military and civilian activities, along with participation by other international organizations (Cockell, 2003: 120).

New multidimensional and multifunctional operations incentivized the UN to review its main documents for peacekeeping, redefining principles, and guidelines for operations. Performed by different international organizations under UN leadership, UNMIK has been one of the major milestones in conceptualizing post-Cold War operations; even if it was not the first multinational peace operation led by the UN. The most important characteristic of the peace operation in Kosovo was its pillar system, which combined various organizations such as OSCE and EU. The flexibility of UNMIK, allowing for functional and structural changes in the pillar system, has been another key characteristic of the mission. Although begun as a UN peacekeeping mission, the peace operation in Kosovo became a civilian task performed mainly by the OSCE, and especially by EULEX, after 2008. Thus, since the beginning the mission in Kosovo has experienced peace-making, peace enforcement, peacekeeping, and post-conflict peacebuilding activities (Cockell, 2003: 121).

The essay shows the connection between conflict-poverty-education. The dimension of this hidden crisis and documentation of brutality of violence against school-age children, shook the international community and shows them the lack of efficiency towards such reconstructive programs. With the collapse of communist regimes removing Cold War barriers, the resurgence of nationalist narratives brought the question of national education to centre stage in Kosovo.

The country, which after the fall of communism embarked on a long battle for independence and statehood, serves as a case in point to analyse and discuss how education acquired a crucial role. With the emphasis in education policies, the international community that stepped into Kosovo attempted to shift the focus from separate ethnic claims towards a common multi-ethnic identity. The outcomes showed that the struggle for multi-ethnicity, multiculturalism and inclusiveness has been fueled by conflicting international and local agendas on the role of education in the new state. The internationally driven ‘liberal peace’ agenda has strongly focused on stability and security and has emphasized equal collective rights and extensive decentralized autonomy for different ethnic communities. Local actors, however, perceived education as an arena for exclusive national and ethnic claims and some of the externally driven reforms were used to further segregation of the education system and reassertion of ethnic control. International actors’ strategy of emphasizing collective rights, and decentralized governance of education, has enabled education segregation. Such strategy has empowered local elites to resist all-inclusive education and has made communities to pursuit ethnically segregated education, resulting in further separation between already divided ethnic groups (Ervjola, 2018: 15).

This separation is captured in higher education and the phenomena of universities’ ethnic dualization. The development of the University of Pristina and other public and private universities in Kosovo has been used by Kosovo Albanian political elites to consolidate, legitimize their power base. The result has been an education system that reflects and reproduces a model of segregated and negative peace. The functions of education can be thus seen as the result of two diverging agendas. On the one hand, the international community, through its focus on community and minorities education, sought to support a multi-ethnic education system as the foundation for a new multicultural polity that transcended the experience of nation-state and could be integrated into the EU. On the other hand, local elites (either Kosovo Albanian or Serbian) have side-tracked these efforts, incorporating education as part of the process of building a society that remains mono-national or thus ethnically exclusive. The result is an education system that reflects such tensions between multiculturalism and nationalism, ethnic segregation, and Europeanization, and rampant clientelism and political control. It is this clash and tension between various agendas that has re-defined and shaped the role of education in post-conflict Kosovo (Ervjola, 2018: 16).

Defining the multi-organizational structure in detail, performing joint exercises, and training, and preparing common operational documents before deployment, would help ensure better coordinated peace operations in the future. Multidimensional peace operations will succeed most when the interests of international and regional organizations converge. Without this convergence and cooperation, the goals temporarily achieved would not survive into a long-term strategy.

Bibliography

Bush, K.D., and D. Saltarelli. 2000. The Two Faces of Education in Ethnic Conflict. Innocenti Research Centre. Florence: UNICEF.

Charter for Change (s.d.) Charter for Change. Disponibile su: https://charter4change.org/ (Accessed: 24 May 2023).

Choedon, Y. (2010) ‘The United Nations Peacebuilding in Kosovo: The Issue of Coordination’, International Studies, 47(1), pp. 41–57. doi: 10.1177/002088171104700103.

Cockell, John G. “Joint Actions on Security Challenges in the Balkan”, Michael Pugh and Waheguru Pal Singh Sidhu (eds.), The United Nations and Regional Security: Europe and Beyond, Boulder, Lynne Rienne Publisher, 2003, pp. 115-136.

Duijzings, G.H.J. (1999) Religion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo. PhD thesis. Universiteit van Amsterdam. Availbale on: https://dare.uva.nl/personal/pure/en/publications/religion-and-the-politics-of-identity-in-kosovo(6811d877-98bf-4a6d-9f2f-676defba5fa1).html

Ervjola Selenica (2018): Education for Whom? Engineering Multiculturalism and Liberal Peace in Post-Conflict Kosovo, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, pp. 1-22.

Fischer, B. J. (1985) ‘Italian Policy in Albania, 1894-1943’, Balkan Studies, 26(1), pp. 101–112.

Generalità – Difesa.it (s.d.). Availbale on: https://www.difesa.it/OperazioniMilitari/op_int_concluse/KosovoUNMIK/Pagine/default.aspx (Accessed: 24 May 2023).

Hosmer, S. T. (2001) “The Conflict over Kosovo: Why Milosevic Decided to Settle When He Did”. Rand Corporation.

Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale (2009) Indipendenza del Kosovo. Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale. ISPI. Availbale on: https://www.ispionline.it/sites/default/files/pubblicazioni/Indipendenza%20Kosovo%202-2009.pdf.

Jarstad, A., & Belloni, R. (2012). Introducing Hybrid Peace Governance: Impact and Prospects of Liberal Peacebuilding. Global Governance, 18(1), 1-6.

Josip Broz Tito | Biography & Facts (s.d.) Encyclopedia Britannica. Available on: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Josip-Broz-Tito (Accessed: 24 May 2023).

La Storia del Kosovo (s.d.). Available on :http://www.italia-liberazione.it/novecento/antecedenti.html#:~:text=Nel%201877%2D78%20avviene%20un,serba%20%C3%A8%20intorno%20al%2025%25. (Accessed: 24 May 2023).

United Nations mission in Kosovo, UNMIK, Mandate (2016). Available on: https://unmik.unmissions.org/mandate (Accessed: 24 May 2023).

Martina Spernbauer, EU Peacebuilding in Kosovo and Afghanistan: Legality and Accountability, Leiden, Martinus