DIGITISATION IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES: CYBERSECURITY CONCERNS, CORPORATE RESPONSES, AND GOVERNMENT STRATEGIES By Manel Bernadó Arjona

April 2021 – Accepted by Blue Europe Committee of Publication on the 15/05/2021

As technology grows in complexity and further embeds in social and economic relations of all kinds, the exposure to cyber threats increases, and so does the relevance of constantly developing and implementing proper cybersecurity systems. This is especially true for Central and Eastern European countries (hereinafter, “CEE”), whose capacity to face cyberthreats generally remains subpar vis-à-vis other EU member states.

Cybersecurity threats have deep implications, from data breaches and ransomware, to attacks on critical infrastructure. As the NIS Directive suggests, the national security implications of these threats require governments to assume a leading role in pursuing a high level of security by establishing cybersecurity strategies and maintaining a set of minimum capabilities at all times. However, even where these strategies have effectively been developed, they fail to prevent the majority of cyberattacks against businesses and individuals. In this regard, governmental institutions cannot, in practice, prevent, monitor, and respond to cyberattacks against the private sector on their own. Thus, companies have been forced to assume the challenging endeavour of developing and maintaining cybersecurity systems that repel and minimize the impact of cyberattacks.

Cybersecurity concerns grow across the globe and in all industries as the frequency and severity of attacks continue to surge. As a consequence, the cybersecurity industry has grown as much, increasing by a third (33.83%) in the past 3 years. In absolute terms, the global market –encompassing any means of protecting information systems, hardware, network, and data from cyberattacks– has increased from $137.64B in 2017 to $184.19B in 2020. At a compound annual growth rate of 10.2%, it is projected to reach $248.26B by 2023, almost doubling in 6 years (STATISTA 2018).

According to the Cyber Risk Index (NordVPN 2020) elaborated by NordVPN, factors such as a higher-income economy, advanced technological infrastructure, and the process of digitization in a country, inter alia, contribute to increasing the vulnerability and exposure a country has to cyberattacks, and empirically correspond to higher degrees of cybercrime.

This relationship would explain why Central and Eastern European countries have not been among the most exposed countries to cyberattacks in the past two decades. As their economies grow and move towards digitisation, they will indeed become more vulnerable and attractive for prospective cyberattacks. Political turmoil with neighbouring countries and the apparition of digital hybrid warfare dramatically increase the prospects for CEE countries to be targeted by state-sponsored cyberattacks (CSIS 2016). To cope with this changing environment, CEE countries should guide their economic growth and digitisation process with proper government and corporate strategies that prevent, deter, and counter cyber threats.

This article aims at providing a data-based analysis on the progressive digitisation process in CEE countries in the past years, assessing its cybersecurity implications, and describing the private and public responses undertaken to tackle cybersecurity concerns in CEE countries.

-

Digitisation in CEE Countries

Just like their European neighbours, CEE countries have embraced digitisation as a key factor for growth. Digitisation provides a unique opportunity to overcome economic challenges, and come out of the COVID-19 crisis stronger than ever. Efforts to develop a substantial digital infrastructure, alongside the lack of legacy industries, can help propel their individual national and overall regional growth in these difficult times. A 2018 report by McKinsey estimated that digitisation in CEE countries could add more than $200 billion to regional GDP by 2025, with the IT industry growing to represent up to 16% of their GDP (Digital McKinsey 2018).

The digitisation process is nowadays employed as a vague, widely used term, and the reality of progressive digitisation is assumed anywhere in the world. What does digitisation actually translate to in CEE countries, and what implications does it entail?

Public data on relevant indicators obtained from Eurostat and the OECD offers a glimpse at the upward trend in the use of IT products and services across CEE countries in corporations, households, and new forms of e-government. For matters of simplicity and representativeness, this article analyses data from Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and Lithuania. The aggregated values for the European Union (without the United Kingdom) are included for comparison.

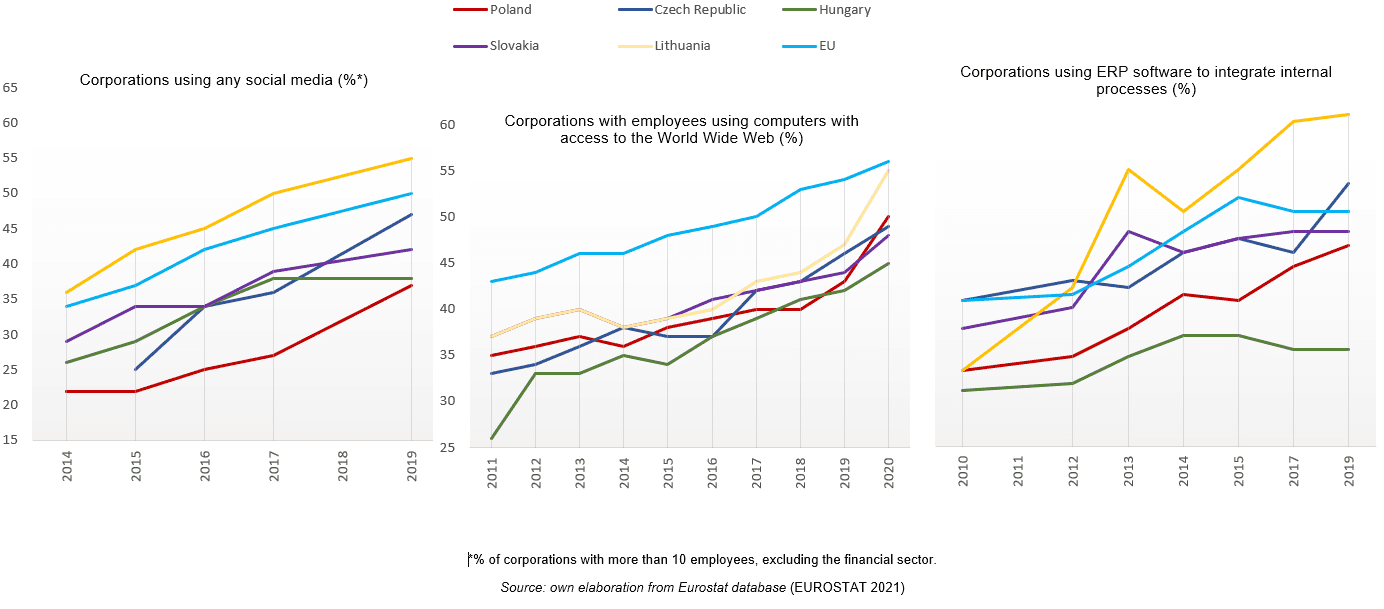

Corporate Digitisation

How have companies in CEE countries incorporated IT products and services to adapt to new market realities? Have they found innovative solutions to business problems? This can be assessed in several ways. Around half of corporations in CEE countries currently use social media to interact with the market, and half of them have employees who use computers with internet access in the workplace. We also witness the rise in the use of Enterprise Resource Planning software to integrate internal processes for e-commerce practices implies deep, structural company digitisation.

Most of the CEE countries analysed here generally follow a similar upward trend. Lithuania is positioned at the head in all charts, being the CEE country with the most digitised companies. Its corporations have increased the use of computers with internet access and social media by approximately 50% in nine and five years, respectively. Most impressive has been the evolution of Lithuanian companies of ERP software usage, increasing more than 330% in nine years and positioning the country above the aggregate EU level.

Lithuania is followed by the Czech Republic and Slovakia, which have witnessed similar paths in corporate digitisation, achieving a certain degree of parity with EU levels across most indicators. The least performing CEE countries of those analysed are Poland and Hungary, which started with the lowest levels of digitisation but still have increased in all fronts, with more or less intensity, and with some exceptions.

Overall, CEE economies show empirical signs of progressive digitisation, following the trend of their Western neighbours of further incorporating IT products and services in their business models and structure, as well as in the ways they interact with their costumers.

*% of corporations with more than 10 employees, excluding the financial sector.

Source: own elaboration from Eurostat database (EUROSTAT 2021)

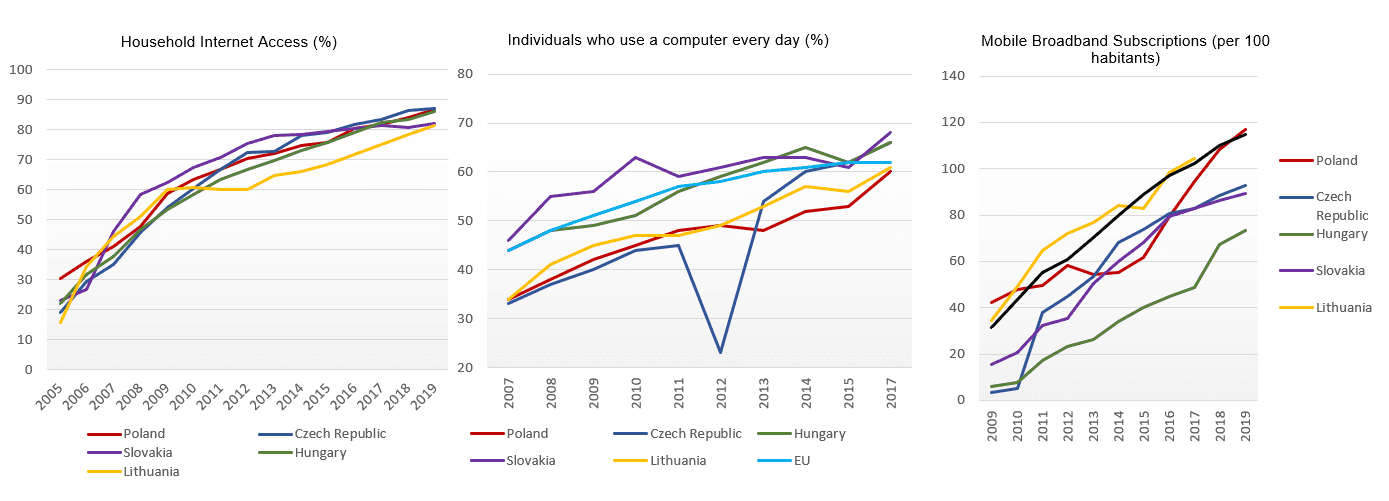

Digitisation in Households

We can measure digitisation at an individual level, by observing the extent to which households have access to computers and the internet, and the frequency with which they use them. Indicators such as household internet access, mobile broadband subscriptions or the proportion of individuals using computers every day serve this purpose.

Source: own elaboration from OECD (OECD 2021a) (OECD 2021b) and Eurostat database (EUROSTAT 2021)

In the past years most of the population in CEE countries has acquired access to the internet, moving from an initial range between 15 and 30% of the population in 2005, to one between 80 and 90% in 2019. Access to the internet has therefore become the mainstream reality for the vast majority of their population.

Furthermore, the amount of individuals using computers on a daily basis skyrocketed in the last decade in all analysed CEE countries and the EU as a whole. The figures show how the everyday use of PCs almost doubled in Poland, the Czech Republic and Lithuania. Overall, regional CEE levels are between 60 and 70% of their population using computers every day.

Likewise, the widespread use of smartphones with internet access has fostered a steep rise in the amount of mobile broadband subscriptions in CEE countries. These subscriptions are understood as those allowing data speeds beyond 256 kbit/second, granting access to internet via HTTP, and having a data connection through the Internet Protocol (IP). In some cases, these subscriptions have almost doubled in the past 10 years: in Lithuania they went from 34 to 61; in the Czech Republic, from 33 to 66. In other CEE countries, such as Hungary or the Czech Republic, they have multiplied tenfold from almost inexistent levels a decade ago.

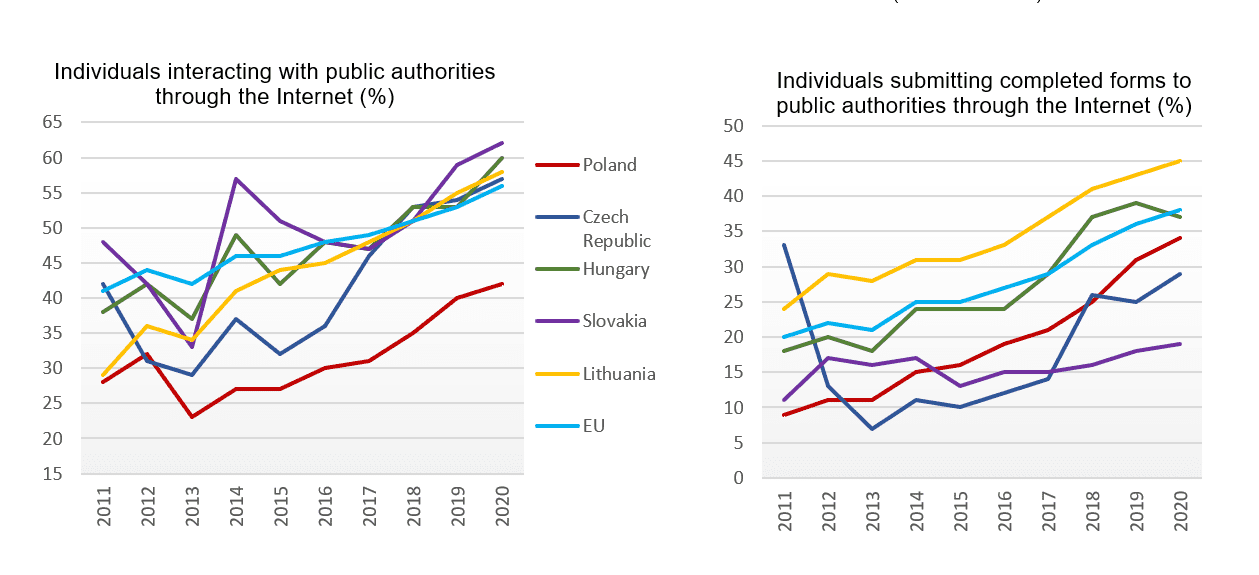

E-Government

Public institutions have also entered the digital era by automatizing processes and changing the way in which they interact with their citizens. The proportion of individuals interacting with public authorities through the Internet has substantially increased. Although in some CEE countries such as the Czech Republic and Slovakia there was a decrease in this sort of interactions from 2011 to 2013, currently more than half of the interactions with public authorities in CEE countries take place through the Internet, at levels that surpass the EU aggregate. The only exception for this is Poland, which falls behind from its CEE neighbours despite increasing by 50% the proportion of its online government interactions in nine years.

In addition, data reveals an upward trend in EU citizens submitting forms filled with their personal data to public authorities through the internet, going from around 20% to over 35% of individuals carrying out this practice. Lithuania has outperformed the EU, and Hungary and Poland have reached levels similar to those of the EU aggregate. The Czech Republic is, in this regard, a particular case: despite experiencing a drop from 33% to 7% in the 2011-2013 period, it has complied with the upward level of the CEE region ever since and is now in synchrony with its peers. Slovakia falls short by moving from 11% in 2011 to 19% in 2020.

Source: own elaboration from Eurostat database (EUROSTAT 2021)

(Continues in part 2)